“Jesus gave His life as a ransom for many”

Posted on 04 June 2013, 14:11

For almost 60 years as a priest in the Anglican Church I have been saying the words, “The Body of our Lord Jesus Christ, which was given for thee, preserve thy body and soul unto everlasting life. Take and eat this in remembrance that Christ died for thee, and feed on him in thy heart by faith with thanksgiving.”

Probably most of us treat these words as a kind of poetry, suggesting the depth of our communion with the Risen Christ and with each other, and we would be right to do so. Failure to do this, in the past, has led theologians to formulate some very strange dogmas, the source of much dissension.

If we take those words literally, we seem to be saying something very odd: that the Communion bread is actually the physical body of Jesus, and that it will somehow save our bodies and souls into eternity; theologians have said that the giving or sacrifice of the body by Jesus does this, because by allowing himself to be crucified Jesus ransomed us from the powers of evil. Thus he became our Redeemer. (They based this on the passage, Mark 10:45 - “gave his life as a ransom for many.”)

Let’s first discuss the idea “ransom” - In the late 2nd century Irenaeus of Lyons argued that Jesus’ death was a kind of ransom paid to the devil to save believers from the results of their sin.

This view became Christian orthodoxy for the next 800 years until Anselm of Canterbury (ca. 1033-1109) pointed out that this theory gave the devil far too much power. Hence Anselm gave a different answer: Jesus’ life was paid as a ransom not to the devil, but to God. Anselm’s idea was that was that God’s justice demands punishment for sin, and Jesus had to take that punishment by dying on the cross, freeing believers from the consequence of sin. Anselm’s view has become the orthodoxy of several branches of Christianity until the present day. The belief is seen in a multitude of hymns and choruses, of which the following verse is an example:

“He paid the debt that he did not owe

What came from His hands, His feet and His side

Was more precious than silver or gold

The blood that set me free

It came from a life of sin and tragedies

I’m born again, free from sin

Because of the blood..”

While readers of this article may or may not have such beliefs, it would nevertheless be interesting to know what the writer of the gospel of Mark had in mind when he used those words “ransom for many.”

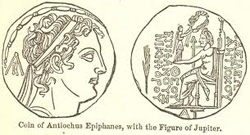

I think the answer is to be found in a Jewish document describing events that occurred around 150 BCE, called The Fourth Book of Maccabees. They were before the Roman occupation of Palestine when the Greek tyrant Antiochus Epiphanes was trying to subjugate its people, and to wipe out the Jewish religion, together with the Temple worship. Antiochus was especially keen to abolish Jewish food laws, in particular the prohibition against eating pork. Now, there was a certain widow of a priest, who had seven sons, and they refused to eat the pork. Much of the Fourth Book of Maccabees is devoted to describing the death by fiery torture of each member of the family in turn. After all that, we read a suggestion for what could be inscribed on their tomb: “Here lie an aged priest, an aged woman, and her seven sons, Through the violence of a tyrant who desired to destroy the polity of the Hebrew race, They vindicated our nation, looking unto God, And enduring torments even unto death….. They became as it were a ransom for our nation’s sin, and through the blood of these righteous ones and their propitiating death, the divine Providence preserved Israel which before was evil entreated.”

[my italics]

We can’t accurately date the writing of this version of the story, but it has been suggested that it was done some time when Jesus was alive. This powerful story is likely to have inspired the contemporaries of Jesus struggling under the heel of the Romans, and to have been in the mind of the writer of the gospel in talking about the death of Jesus. His death, like that of the widow and her seven sons, was as it were a ransom for many, a propitiatory sacrifice, the price that had to be paid to stiffen people in their true faith, and to keep them from evil.

Eight hundred years of following Irenaeus, and a thousand with Anselm, would have been avoided if the ransom metaphor had not been taken as a pseudoscientific fact. Or perhaps not even that, but rather a kind of act of magic. Spiritual and poetic truth is made nonsense of by the language of the market place.

Similar problems have dogged Christianity with regard to the Bread and the Wine, in the Mass, or Communion Service. Here again a potent metaphor for Communion with the Divine and with each other, has been turned into some kind of magic. The Bread that you receive at the hand of the priest is said to be truly and literally the physical body of Jesus, and it will convey God’s grace to you. If we were to say that the mere act of swallowing the Bread gave one grace, then we would be in the realm of magic. On the other hand one could well imagine that deep faith that the Bread was Christ might well initiate true communion with the spirit of Christ. In such matters people of varying Christian beliefs should be wary of judging the spiritual lives of others. All sorts of language can be a cover for hidden depths of relationship.

It may be the case these days that some priests and people treat these words as a kind of poetry, and simply take the receiving of the Bread and the Wine as an act of Communion with each other and with the universal Christ, the spirit of God. Over the past 2000 years however there have been many controversies over the meaning of the ceremony, with the Orthodox branch of Christianity splitting from the Catholic branch in 1053 over whether Christ was of the same substance or like substance to God, and in 1517 when the Lutherans split from the Catholics who affirmed that the Communion Bread really was the physical body of Jesus (Consubstantiation), affirming instead the Real Presence of Christ in the Bread. But even the latter affirmation taken literally prompts objections: In what way is Christ present in the Bread? Is Christ somehow confined to the Bread? ..in a material object? Is he only present to the eye of faith?

Plainly the simplest thing is to see Christ in the Bread as a kind of poetry conveying in sensory-physical language a real relationship in Spirit. Even a philosophical Materialist could agree to that description.

But if we are not philosophical Materialists, we will want to affirm that somehow Spirit or Mind, not Matter, brings all things into existence. We will agree that the words are a kind of poetry, but will want to say more than that. To begin with we will agree with Materialists, that so far as the realm of See-and-touch goes, we all need to weigh and measure and say, “Here is a kilo of cheese. I will sell it to you for eight dollars. You will find many other varieties of cheese on the shelves. You will have to walk 25 metres to find them.” We can call this the Sensory-Physical mode of regarding reality.

But this is not the way of seeing things that we find in the New Testament. The writer to the Ephesians in chapter 4 talks about a God in whom we live and move and have our being. The Gospel of John speaks of Christ as being the Vine, and us as the branches, or in Chapter 17 of Jesus being in the Father, the Father in us, and we in them. St Paul repeatedly writes of our being in Christ, members one of another. Plainly these writers are seeing reality from a different point of view, seeing us as participants in an indivisible realm of Spirit that has its effect on the world we perceive with our senses. That realm, is the realm of the mystic, the psychic, the person who prays, and indeed that of quantum physicists trying to understand how the universe works.

The mistake of Irenaeus, Anselm, and some later theologians was to confuse the indivisible realm of Spirit, as just described, with the sensory-physical mode of understanding things. They seem to regard the Communion Bread as a thing like cheese: this piece of bread in your hand is literally the body of Christ, or in this bread Christ is really present. Their mistake can have sometimes have led those who believed them into the possibility of superstition, rather than into Communion with the Spirit of Christ that fills the universe.

The hymn, St Patrick’s breastplate gets it absolutely right:

Christ be with me, Christ within me,

Christ behind me, Christ before me,

Christ beside me, Christ to win me,

Christ to comfort and restore me.

Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ in quiet, Christ in danger,

Christ in hearts of all that love me,

Christ in mouth of friend and stranger.

The mystic, the spiritual person is relating to reality in the Clairvoyant/Holistic mode where we see everything as aspects of one inseparable whole: we are conscious participants in the universe, distance does not separate our minds, whether they are in the body, or not. When we pray we assume that time and space will not separate us from those for whom we intercede. When we experience paranormal events, clairvoyance, telepathy, communications from the dead, inspiration, all forms of intuition, and especially when we have Communion, we are seeing spiritual-physical reality as an indivisible whole. Reality is what it is, it is just that we can see it from the point of view of the sensory physical, or from the point of view of the clairvoyant or holistic. The same reality seen from two utterly contrasting modes, or points of view.

When we pray with Jesus in mind, we should perhaps not focus too strongly on the physical, historical man. That could lead us to praise him as some sort of Saviour out there, rather than entering the salvation of knowing that we are participants in the universal Christ, the Christ most often spoken of by St Paul and St John. The historical Jesus pointed the way. We should look not so much at the hand that points, as to where it points.

When we take Communion, I believe we should understand that bread and wine as symbols of the universal Christ, the universal Self in which we participate. And it was not the death of the body and the shedding of the blood of Jesus that saves us, but rather that his resurrection after the death of his body saves us by showing us that death is almost meaningless, and that we are always citizens of heaven, participants in the universe: that death is not the end, the whole is eternal.

Footnote: Celts and their praying to the Trinity.

“God, for the Celts, is always Triune – the Three-in-One – and they served this great paradox well. They never allowed the Father and the Son and the Spirit to become separate. Celts thought of God as the “three of my love.” With the While they held an adoring view of the Trinity their perception never became either too syrupy or too formal. A strong Trinitarian formula pervades the whole of Christian Celtic literature. Consider this simple prayer for grace:

I am bending my knee

In the eye of the Father who created me

in the eye of the Son who died from me

in the eye of the Spirit who cleansed me.

… The God who creates and pervades the natural world is never separate from the Son who redeems, nor the Spirit who indwells each believer.

From: Calvin Miller: The Path of Celtic Prayer: An Ancient Way to Everyday Joy 2007

Michael Cocks edits the journal, Ground of Faith.

Afterlife Teaching From Stephen the Martyr by Michael Cocks is published by White Crow Books and available from Amazon and other bookstores.

Paperback Kindle

|