|

“I don’t need great faith. I have great experience.”

— Joseph Campbell

Why do we search for God? It may be that our need to lead meaningful rather than absurd lives is even more powerful than our desire to reduce our suffering or to pursue happiness. When physician Herbert Benson claims “We are hardwired for God,” he is saying that from the beginning of human life we have reached out for a connection to something greater than ourselves.

Even the earliest societies sought some power outside themselves to provide understanding and control of the inexplicable around them. They worshipped the power of the sun, fire, rivers, storms, even geographical features — all elements most people today consider unconsciousness and thus uncaring.

Maybe more than needing to explain God, our ancestors felt the need to access the power of transcendence. We know, for example, that these early men and women often sang and danced through the night, sometimes while ingesting powerful mind-altering plants, in order to experience a power beyond themselves and their difficult lives. We know that rhythmic body movements sustained for long periods of time also alter consciousness. In more recent times, Sufi Whirling Dervishes, dancers from all cultures, runners, skiers, gymnasts, and other athletes have all found, through movement, a way to stop their ordinary mental processes and experience the overwhelming feeling of oneness available to all who step outside the ordinary.

Even children love the thrill of spinning round and round to lose their sense of space, time, and separateness.

Many perceive that something meaningful exists beyond their mundane experience of the world, but they usually encounter it only when they fall in love. One reason overpowering feelings of romantic love are so satisfying is that we finally begin to focus our attention outside ourselves. Maybe the secret motivation many mystics have for spending their lives in silence is to experience this feeling of transcendent love all the time! But, the love of God is an unsentimental love with neither an object nor an agenda; the great surprise is that it’s available to anyone who takes the time to find it.

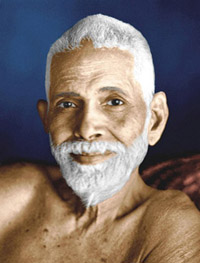

Ramana Maharshi, (below) said to be one of the wisest and most enlightened Indian teachers, spent most of his life silently meditating in a mountain cave. One possible answer to why he would do that comes from philosopher Andrew Cohen, who defines enlightenment as the surrender of the ego-mind to the perfection of the cosmos, and the ability to express that perfection. In Christian terms, it might be achieving a self-aware life, walking with God, in what is called “prayer without ceasing.”

It is, of course, much easier for Maharshi to experience God while peacefully sitting on a rock in India than it is for an overworked engineer at her computer in Silicon Valley, but you have to start the search somewhere.

Maharshi’s teaching of self-inquiry guides the seeker on a relentless quest to find and experience God — the love at his or her core. We are instructed to first ask, “Who am I?” — and then, “Who wants to know?” In discussing Ramana Maharshi’s contribution, philosopher Lex Hixon writes, “Ramana may be the Einstein of planetary spirituality transcending previous approaches to religion, as the General Theory of Relativity transcended earlier more parochial theories of physics.”

The American mystic given the name Gangaji (little Ganges) by her Indian mentor H.W.L. Poonja is a contemporary teacher in the lineage of Maharshi. Gangaji is a beautiful, charismatic woman from northern California who teaches self-inquiry as a path to experiencing the truth. In one of her meetings — called satsang, or association with truth — a man in the audience said to her, “You have changed my life. But I don’t know what to do.

I’m in love with you!”

Gangaji replied, more or less, “Of course you’re in love. That’s okay. But don’t get attached to this body or form. As you know, bodies come and go. But I’m happy for you to join me in love.

That is your own true nature.”

In our experience, Gangaji (below) is an exemplar of one who lives the truth she teaches, and encourages others to join her. She not only teaches the Perennial Philosophy but also demonstrates and transmits for all who spend time with her the experience of a heart bursting with love — what Jesus called, “The love that passes all understanding.” She reminds (re-minds) anyone so fortunate as to have a transformative heart-bursting experience in her presence that “this limitless love you are now experiencing is always available. It is who you are.”

In Chapter 7 we describe this experience of being overcome with love as an orgasm of the heart. It isn’t romantic, but an experience of what Buddhists call sunyata (emptiness or the absence of independent existence) and Hindus call Advaita Vedanta (the truth of not-two). This description of unity consciousness has not changed since before the time of Buddha, who taught, “When your mind is filled with love, send it in one direction, then a second, a third and a fourth, then above, and then below. Identify with everything, without hatred, resentment, anger, or enmity. The mind of love is very wide. It grows immeasurably and eventually is able to embrace the whole world.”

The experiences mystics have described since the beginning of history are the focus of what is today called Transpersonal Psychology — psychology beyond the self. Ken Wilber describes it as the part of our being wherein “Spirit knows itself in the form of Spirit.” It is not a return to babyhood, where ignorance is undifferentiated sensation and bliss. Rather, it is expanded awareness: where we have the surprising opportunity to realize that loving your neighbor is indeed the same as loving yourself.

Jung argued that Freud was seriously mistaken to consider transpersonal experience as a return to the pre-personal “id” of toddlers, who have yet to separate their personalities from their mothers. We agree with Jung: freedom comes from awareness, not ignorance. We discuss these ideas further in Chapter 6.

Once people experience their true nature as transcendent consciousness, connected to all living beings, they may find many things in their life that need changing, in addition to realizing that they themselves are forever changed. As the Hindu saying describes, “Once the elephant has entered the tent, the tent will never be the same.”

The Perennial Philosophy

The philosopher Aldous Huxley attempted to distill from the world’s religions, with their “confusion of tongues and myths…a Highest Common Factor which is the Perennial Philosophy in what may be called the chemically pure state.” Huxley wisely warned that “this final purity can never, of course, be expressed by any verbal statement of philosophy.” This brings to mind the old aphorism, “Those who know don’t say. Those who say don’t know.” We — each of us — just do the best we can.

In our quest for a comprehensible spiritual life, we have taken Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy as the enduring religious elements that stand the test of time and remain with us. We seek to present these elements in a framework that is in agreement with the modern mind’s passionate desire for coherence and consistency. We understand that to be successful in interesting a scientist in prayer, we must present an ontology that doesn’t offend his or her rational mind. What a task!

We must first acknowledge that science very successfully describes one aspect of human experience: the material universe. On the other hand, science has little to say about many other things we experience, such as love, and spiritual feelings.

These universal feelings, expressed throughout history, have been the source of Huxley’s distillation of the world’s religious teachings. Here is our understanding of Huxley’s four enduring elements of the world’s spiritual truth:

1. The world of both matter and individual consciousness is manifested from spirit. The world is more like a great thought than a great machine.

Physicist Amit Goswami has written widely on this issue, teaching that “consciousness is the ground of all being.” He writes, “In Quantum Physics, objects are seen as possibilities….It is consciousness, through the conversion of possibility into actuality, that creates what we see manifested. In other words, consciousness creates the manifest world.”7 He goes on to explain, “The universe is self-aware, but it is self-aware through us.”

When Jesus taught, “The kingdom of God is within you,” he might have meant that the thoughts and consciousness of the entire nonmaterial universe are available to each person’s expanded awareness. This ancient truth, combined with Goswami’s modern view that “consciousness manifests the world,” suggests that we should not be surprised by new scientific evidence for the efficacy of prayer.

2. “Human beings are capable of not merely knowing about the Divine Ground by inference,” Huxley writes. “They can also realize its existence by direct intuition, superior to discursive reasoning.” He continues, “This immediate knowledge unites the knower with what is known.” For the prophet Muhammad, a philosopher without the personal experience of his own philosophy is “like an ass bearing books.” In the Koran, God tells Muhammad, “I am closer to you than your jugular vein.”

This idea has great contemporary currency in quantum physics. The distinguished American physicist John Archibald Wheeler observed that we live in a participatory universe, where there is little if any separation between the observer and the observed.

In parapsychology research, this would be called “direct knowing,” for which there is already voluminous evidence from research in mind-to-mind connections, distant healing, remote viewing, and many other areas we describe in the next chapter.

3. Man possesses a dual nature: both an ego associated with our personality and our mortal, physical body, and an eternal spirit or spark of enduring divinity. It is possible, if a person wishes to, to identify with this spirit, and therefore with what Huxley calls “the Divine Ground,” or universal consciousness. After more than one hundred years of investigation, compelling evidence now exists that in addition to this divine spark of spirit, some aspect of our conscious and unconscious memories survives bodily death. Not that we would put off any current plans for our “next lifetime,” but data from children who remember their previous lives is now quite strong, as we will explore in Chapter 4.

4. Finally, the Perennial Philosophy teaches that our life on earth has only one purpose: to learn to unite with the Divine Ground and the eternal, and to help others do the same. Buddhism refers to the bodhisattva, a being who has become one with “all that is,” and returns to help all living beings. The bodhisattva doesn’t distinguish between who is being helped and who is doing the helping because he or she is in a state where there is no separation. As the revered Vietnamese Zen Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us, when the left hand is injured, the right hand does not stop to point out, “now I am taking care of you.”

This extension of one’s awareness expresses itself as universal love, or a purpose larger than ourselves. As Viktor Frankl writes in his introduction to Man’s Search for Meaning, “Success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue…as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a course greater than oneself.” Finally, Brian Swimme writes in his inspiring book The Universe Is a Green Dragon, “That our fullest destiny is to become love in human form. ...Love is the activity of evoking being, of enhancing life. The supreme insistence of life is that you enter the adventure of creating yourself.”

This adventure of “evoking being” by “becoming love” echoes the Perennial Philosophy’s message of personal transformation of consciousness. It tells us that we are here to learn to unite with the Divine Ground, but it neglects to tell us how to do it.

Historically, there have been, and are, many ways to cohere our lives with the teachings of the Perennial Philosophy. These spiritual technologies for uniting one’s consciousness with God are teachings that emphasize the experience of God over religious dogma.

Questioning Authority

Most of us have seen the popular 1970s bumper sticker that read, “question authority.” A reading of the earliest Buddhist writings illustrates the preeminence that Buddhism gives to direct experience and the questioning of authority. In addressing a group of villagers at Kalamas, the Buddha says:

Come, O Kalamas, do not accept anything on mere hearsay. Do not accept anything on mere tradition. Do not accept anything on account of rumors. Do not accept anything just because it accords with your scriptures. Do not accept anything merely accounting for appearance. Do not accept anything just because it agrees with your preconceived notions. Do not accept anything thinking that this ascetic is respected by us.

When you know for yourselves — these things are moral, these things are blameless, these things are praised by the wise, these things when performed and undertaken, conduce to well-being and happiness, then do you live and act accordingly.

These words of 2,500 years ago retain their great wisdom today. Such thinking is the hallmark of a spirituality that moves beyond belief. Don’t believe everything you hear, even if it is said by the Buddha. Instead, investigate for yourself and see what is revealed. There is no approximation in direct experience. This is Buddhism’s appeal for the questioning mind.

One starting point for such an inquiry are Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths. The description we give here comes from the wise and heartful Buddhist teacher Sylvia Boorstein, who is also an observant Jew. The gentle approach in her book It’s Easier Than You Think is an example of wonderfully applied Buddhism.

The Four Noble Truths have come down to us from 500 bc India. They describe the human condition and make recommendations for bringing meaning to our lives, and in many ways are parallel to Huxley’s statement of the Perennial Philosophy. They are also reflected in many of the great religions’ esoteric teachings, including Gnostic Christianity and Kabbalistic Judaism.

The First Noble Truth is indisputable: we experience pain because we are aware of the finite, fragile, temporary nature of our lives. Buddhism is a philosophy of self-control of one’s mind.

If we cannot take charge of our own churning thoughts, how can we take control of our lives in the physical world? As Sylvia Boorstein says, “Pain is unavoidable, but suffering is optional.”

Suffering comes from the story we attach to the pain — the blaming and dwelling. A Course in Miracles teaches a similarly hopeful idea: “I give all the meaning it has, to everything I experience.” This is how Victor Frankl was able to find meaning and spirituality in a concentration camp.

Suffering is subjective. Consider the following: One of the worst punishments inflicted on prisoners is solitary confinement. At the same time, some people from northern California pay thousands of dollars a month for a similar experience but call it a meditation retreat.” The meditator enjoys the experience partially because it’s voluntary but also because he or she knows what to do with the mind to create an opportunity out of the solitude, rather than a punishment.

The Second Noble Truth addresses the suffering caused by craving and attachment. It describes how a life lived at the materialistic end of our map of experience in Chapter 1 leads to desperation. This craving for stuff, money, and accomplishments profoundly interferes with our passionate enjoyment of where we are now, in the present. A core Buddhist precept teaches that making distinctions unavoidably leads to both error and suffering. Imprecision inevitably follows when you judge and divide this from that. Buddha taught this concept from direct observation, and now quantum theory has formulated it into a fundamental “indeterminacy” principle of the universe. We should always remain discerning and courageous in the face of injustice, but judgment gets us into trouble — especially judgment of others.

It all goes back to meaning. We can all remember standing with someone in front of a closet full of clothes as he or she cried, “I don’t have a thing to wear.” And it was true. None of the clothes were new or appealing. They had been drained of meaning, through familiarity, and therefore were nothing.

One final insight into the pain of attachment comes from the Tenth Commandment of the Bible. “Thou shalt not covet” is the only commandment that doesn’t pertain to deeds. It just deals with thoughts! It’s possible that coveting and greed are the most corrosive of all human tendencies, leading to the most anguish and damage to society. And our daily dose of radio and television advertising is one of the greatest sources of this pain.

Without doubt, advertising’s goal is to create so much desperate coveting that we seek relief by buying and accumulating objects.

That’s the bad news.

The Third Noble Truth is the terrific good news. As Sylvia Boorstein says, “peace of mind and a contented heart are not dependent on external circumstances.” When we take control of our free-running minds, we have the opportunity to exchange suffering for gratitude: I may not have solved my life’s problems yet, but I can wake up in the morning and focus my attention on gratitude and my connection to the infinite consciousness of the universe, or I can resume my kvetching.

The inspiring story of one man who was able to do this is told by the French writer Jacques Lusseyran in his breathtaking book And There Was Light. Lusseyran demonstrated that what you decide to focus your attention on is what you get. After losing his sight in an accident at age eight, he relied on his inner resources and the help of devoted friends to complete high school and gain acceptance into university just as World War II was on the horizon.

During the Nazi occupation of Paris, Lusseyran recognized that information was the ingredient essential to aiding the Resistance and maintaining people’s morale. With his friends, he formed an underground newspaper right under the eyes of the Gestapo. He alone was chosen to interview each potential member of the growing Resistance band because of his unique gift for intuitively determining who could be trusted. Their underground operation continued for two years before they were betrayed by the one person about whom the blind Lusseyran had expressed doubt.

In the concentration camp Lusseyran occupied himself by finding food for the sickest prisoners. Despite his blindness, starvation, and brutal treatment, he helped build a secret radio receiver and became an inspiration to his fellow prisoners. At the end of the war, he was rescued by the Allies, and lived to become a full professor of history at the University of Hawaii. In his autobiography he declares two truths that his remarkable life revealed: “The first of these is that joy does not come from outside, for whatever happens to us, it is within. The second truth is that light does not come to us from without. Light is in us, even if we have no eyes.” Once again, the Third Noble Truth reminds us that anything we see and experience has only the meaning that we give it.

The Fourth Noble Truth lays out paths we can follow to find the centered and balanced mental stance that will allow us to take charge of our minds. We describe some of these paths more fully in the final two chapters of this book.

Although it is possible to read about these truths, it is vastly preferable to internalize them through contact with an inspired teacher. These roads to happiness and contentment are described in Buddhist terms as the Eight-Fold Path: Right Aspiration, Right Understanding, Right Action, Right Speech, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Concentration, and Right Mind fulness. They are all interconnected, like everything else, but aspiration is the essential first step.

The peace we all wish to experience is achieved through the practice of mindfulness. The only way we know to alleviate our pain, and our longing for love — to be in love — is by stopping our fearful mental chatter and taking control of our mind. Mystical traditions teach that the quiet mind is the most available path for anyone seeking to live in love, or to experience a relationship with God, which we think is the same thing.

Yoga and the Mythic Archer

Organized religions invite us to believe that certain words, objects, rituals, leaders, and codified ethical behaviors compose the recipe for getting God to notice and bestow favors on us.

One difference between the Buddhist and Hindu approach is that the Hindu religion has a pantheon of Gods, with Vishnu as Creator, and Krishna in his many shapes and guises as his incarnation on earth. And all are one in Brahman — the impersonal absolute. Many Buddhist sects, on the other hand, recognize no God at all. Much of mystical Hinduism is known as Yoga.

Yoga in Sanskrit means unity or “one with God.” In Yoga, we are taught that to experience being one with God we simply have to quiet the mind. All the rest is commentary. This is the lesson of one of the most famous scenes in the

Bhagavad Gita.

In the opening chapters of the Bhagavad Gita, the sacred Hindu text written in the first or second century ad, Krishna, the son of God, has a conversation with Arjuna, the mythic and heroic archer, in the field of battle. In this poignant scene, Arjuna tells Krishna that he has uncles and cousins on both sides of the battle field, and that he himself is likely to be injured or killed in the battle. Krishna responds: “Do well, whatever you do. You are a soldier, and dying in support of freedom against tyranny is a noble death. And should you die, don’t worry, you know that I will see you next time.”

“You don’t have to read the Upanishads or the Vedas now,” Krishna continues. “If you will sit down, stop talking, and quiet your mind, then you will know that God is here with you.” This is the fundamental teaching of each of the mystical spiritual paths: Buddhism, Hinduism, Kabbalistic Judaism, Sufism, Gnostic Christianity, and all their modern counterparts. It could be described as the time-tested “sit down and shut up” path to spirituality.

The concept of being still is part of the mystical spiritual wisdom that teaches that personal transformation of consciousness is part of human destiny. The Eastern idea that the purpose of religion is to evoke this transformation began to take hold in the West in the early twentieth century.

Paramahansa Yogananda, as a young Hindu mystic, played a significant role in bringing Eastern spiritual science to the United States. In 1920, he addressed an international conference of religious leaders on The Science of Religion. He taught that religion is whatever motivates all people’s actions; religion is “whatever is universal and most necessary for people.” Since all people want to avoid pain and attain happiness, a person’s religion necessarily consists of these motivations.

Yogananda directly addressed the problem that scientists such as Carl Sagan have in believing in God and other religious concepts:

Change of forms and customs constitutes for many a change from one religion to another. Nevertheless, the deepest import of all the doctrines of all the different prophets is essentially the same. Most men do not understand this….There is equal danger in the case of the intellectually great: They try to know the Highest Truth by the exercise of the intellect alone; but the Highest Truth can be known only by realization….It is a pity that the intellect or reason of these men, instead of being a help, is often found to be a bar to their comprehension of the Highest Truth….

According to Yogananda, all great wisdom traditions have taught that identification of our true selves with our bodies is a mistaken illusion. We are most truly spirit having bodies for a time, rather than bodies having life or spirit for a time. If we can understand that our “selves” consist of nonlocal consciousness, then we can understand how quieting our body-bound sensations and brain-bound thoughts can help us experience our spiritual essence.

Where Were the Christians?

For centuries, religious scholars have known of the Eastern mystics. But it wasn’t until Yogananda spoke in the United States that most Americans became aware of Eastern concepts of mind and consciousness. Helena Blavatsky had already created a significant spiritual movement in the 1890s in Europe, introducing a blend of mysticism (about the direct experience of God) and Hindu Vedanta through her teaching and writing on Theosophy. But it was through the appearance of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi discoveries just after World War II that the world became aware of the roots of mystical Christianity. These early writings of the Gnostic Christians revealed great similarities between Hinduism and the religious ideas that appeared during the one hundred years following the death of Jesus. Elaine Pagels, in her Gnostic Gospels, dated the origin of the Gnostic (Nag Hammadi) writings, as approximately 50 to 100 ad, contemporary with the Gospels of the New Testament.In these Gnostic texts, Jesus says, “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” This injunction demonstrates the similarities between the Gnostic or Christian mysticism and Buddhist, Hindu, and Kabbalistic writings. Pagels writes that “to know oneself at the deepest level is simultaneously to know God; this is the secret of gnosis.”In Pagels’ book, another Gnostic teacher, Monoimus says:

Abandon the search for God and the creation and other matters of a similar sort. Look for him by taking yourself as the starting point. Learn who is within you, who makes everything his own and says, “My God, my mind, my thought, my soul, my body.”

Learn the sources of sorrow, joy, love, hate….If you carefully investigate these matters, you will find him within yourself.

The Gospel According to Thomas is a fourth-century manuscript discovered in 1945 near Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt. It contains 114 sayings of Jesus, showing him as a source of mystical teachings. The Gospel of Thomas begins, “These are the secret words which Jesus the living one spoke.” Later, we hear the disciples asking Jesus, “When will the kingdom come?” Jesus replies, “It will not come by waiting for it. It will not be a matter of saying ‘here it is, or there it is.’ Rather, the kingdom of the father is spread out upon the earth for all to see, but people do not see it.”

This teaching reminds us that the kingdom of heaven is here — available in our mind whenever we experience peace and joy. Of course hell is available in the same place, when we reside in anger and fear. We often stand at a personal crossroads, where one sign says, “This way to Heaven,” and the other says, “This way to a workshop on how to get to Heaven.” We then have the opportunity to choose again between Heaven now, or Heaven later.

The Gnostic Christians believed they were each one with God, as well as one with the ascended Jesus, and therefore had no need for bishops, priests, or deacons. They would choose their leader each Sunday by drawing straws. The hierarchy of the Church of Rome was outraged that such an important matter should be left to chance, while the Gnostics said, “We leave it up to God.”

Clement, the Bishop of Rome (c. 90–100), recognized that these free-thinking people were off on their own path. He argued that there is one God, and therefore one Church, and the church of Rome was it.

Gnosticism had the appeal of direct experience. And although the Gnostics were persecuted by the Church of Rome for a thousand years, they continued to find adherents in small and large groups. Then in the middle eleventh century, the Cathari Gnostics, often called the Albigensians because they lived in the Albige (the Toulouse region of southern France), came to the attention of Rome. This ascetic community of almost fifty thousand people shared all their property, and felt they were individually and collectively in continuous communication with God and each other. Rome considered this an intolerable heresy and asked the Noblemen of northern France, including Richard the Lion-Hearted, to make a detour on their Crusade to the Holy Land to kill all the heretic Cathari. In a now-famous exchange of letters, Richard wanted to know how he should determine whom to kill. Pope Innocent III replied, “Kill them all, and God will know his own.” This genocide was an early step in what became the Inquisition, and the end of any kind of organized Gnosticism, which was little known until the recent Nag Hammadi discoveries and translations.

Kabbalah and the Chain of Being

Judaism has somehow successfully kept their religion alive despite the Diaspora and centuries of persecution. This was accomplished in part through teaching reverence for the Torah as their divinely revealed history and guide. They emphasize a word-by-word and letter-by-letter study of this holy book by each individual, together with constant questioning of its interpretation and meaning. This is how the young Jesus in the Bible was able to address and keep the attention of the Rabbis as he revealed his unique interpretation of the Torah.

One problem for Judaism has been that analysis of the text has often replaced the direct experience of something beyond one’s separate self. This omission accounts for the great attraction that Buddhism has for many Jews, because Buddhism offers both an experiential and a comprehensible spirituality. We learn from Roger Kamenetz’s fine book The Jew and the Lotus that more than one third of all the Buddhist teachers in America are of Jewish origin. Recently, however, a significant number of Jews are becoming familiar with the spiritual aspects of Judaism through the Jewish Renewal movement, which incorporates a new interest in the study of the unity and balance found in the mystic teachings of the Kabbalah. Jewish theologian Rabbi Lawrence Kushner writes:

Human beings are joined to one another and to all creation. Everything performing its intended task doing commerce with its neighbors. Drawing nourishment and sustenance from unimagined other individuals. Coming into being, growing to maturity, procreating. Dying. Often without even the faintest awareness of its indispensable and vital function within the greater ‘body.’...All creation is one person, one being, whose cells are connected to one another within a medium called consciousness.

It is thought that the Kabbalah first appeared as a document sometime near the end of the twelfth century. It teaches that every action here on earth affects the entire divine realm, either helping or hindering peace and tranquillity. Kabbalah literally means receiving — making available the received spiritual wisdom of the ancient Jewish mystical tradition. The ten symbols that compose the Kabbalistic “Tree of Life” not only map a spiritual path but also provide a meditative vehicle for potential transcendence. Unfortunately, there is usually more attention paid to the mapping than to the opportunity for transcending thought.

Daniel Matt, in his Essential Kabbalah, writes, “Our awareness is limited by sensory perceptions, our minds cluttered with sensible forms. The goal is to ‘untie the knots’ that bind the soul, to free the mind from definitions, to move from constriction to boundlessness.” From his translation of the Kabbalah:

God is unified oneness — one without two, inestimable. Genuine divine existence engenders the existence of all things. There is nothing — not even the tiniest thing — that is not fastened to the links of this chain. Everything is catenated in its mystery, caught in its oneness. God is one. God’s secret is one, all the worlds below and above are mysteriously one. Divine existence is indivisible. The entire chain is one, down to the last link.

Everything is linked to everything else. So divine essence is below, as it is above. There is nothing else.

This is an idea revealed through direct experience to a meditating mystic undergoing a unitive experience, similar to that of the Buddhists who teach that “separation is illusion.” This compelling feeling of oneness with the universe, and with God, is what motivates people to meditate. Quieting one’s thoughts reveals an awareness that our actions have cosmic consequences, in what we do, what we say, and what we think.

So, every morning we can choose again: will we be fearful and separate, or grateful and connected?

Towering fear, the so-called terror of the “Dark Night of the Soul” described by Christian mystic John Yepes (known as St. John of the Cross) often precedes and impels surrender to this feeling of oneness. Unity Church teaches, “Let go and let God.”

Such surrender is acceptance of living in the mystery. Surrender does not mean “giving up”; it is more an awareness and acceptance of our nonlocal consciousness. It entails releasing total control and acknowledging a greater power in the universe than that found in one’s separate body.

Faith is another form of acceptance based on the experience — often through prayer — of God in our lives. A silent mind and a receptive and waiting attitude come first, creating an opportunity for transcending thought and separate self. Then faith follows.

Faith could be called understanding how the system works. My faith that I can contact my community of spirit when I quiet my mind is based on practice and experience, not on theology, just as my faith that my car will start when I turn the key is based on experience, not something told to me by my Honda dealer.

Science has always had a problem with “faith” in anything but science. But science itself is ever-changing. The sixteenth century Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned alive at the stake for declaring that the earth was not the center of the universe, and today it appears from recent astronomical observations that there may, in fact, be many universes. For a modern physicist, such data come from observing the physical world, and that data changes constantly. Therefore, theories must change. For the mystic, however, the data is his or her experience — and over the past three thousand years the experience of oneness in a quiet mind has been an enduring truth. So, it appears that over the course of millennia, the data of the mystic turns out to be more stable and reliable than the data of the physicist!

The Magic of Mind

We believe that data from contemporary research of psychic abilities — parapsychology — have a part to play in understanding and achieving a useful synthesis of the various mystical experiences described above. We want to emphasize, however, that psychic abilities are not necessarily evidence of a person’s spiritual attainment or awareness. The data for our extrasensory perception show that our consciousness or spiritual nature transcends the body. This evidence is consistent with the Perennial Philosophy underlying the esoteric teachings of the world’s great religions.

Inherent in this universal spiritual philosophy is the idea that human beings are capable of not merely knowing about the Divine Ground by inference but of realizing its existence by direct experience or intuition. This direct knowing is outside the realm of reasoning and analysis. It is possible because, as contemporary physics tells us, we live in a nonlocal universe.

And esp research data show that our consciousness is nonlocal.

In the next few chapters we consider three types of experiences in consciousness that demonstrate conclusively our nonlocal nature, unlimited by bodies or time.

The first type of nonlocal evidence we discuss involves the inflowing perceptual experience of something hidden from ordinary perception. This has historically been associated with divination, crystal gazing, or palm reading. In this book we discuss laboratory experiments investigating much more substantial telepathy, clairvoyance, and remote viewing. These forms of direct knowing are ways in which we make contact with our nonlocal universe, uniting the knower with the known. But psychic abilities do not give evidence for a person’s spiritual development, any more than ordinary sensory abilities do.

Along with the inflowing of perception is the outflow of intention or will. We have evidence for the human capability of distant psychic healing, parapsychological influence on electronic random number generators, and the ability to change the physiology and heart rate of a distant person by staring at their video image.

Finally, in addition to the inflow of information and outflow of intention, there is the quietness of surrender — doing nothing. The mystics tell us about the psychic experiences that may emerge after quieting the ongoing chatter of our mind. These psychic experiences are available to us as we learn to be still.

They demonstrate our mind-to-mind connections throughout space and time but not enlightenment.

Deepak Chopra refers to this ground of awareness in which we are all connected as a dimension of pure potentiality. In his book The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success, which draws upon ancient Vedantic wisdom, he writes, “The source of all creation is pure consciousness ...pure potentiality seeking expression from the unmanifest to the manifest….And when we realize that our true Self is one of pure potentiality, we align with the power that manifests everything in the universe.”

This book is about realizing our true self by consciously aligning our seemingly individual streams of consciousness with this ground of pure potentiality. The opportunity for transforming ourselves by joining our consciousness with this pure awareness is unlimited. In the following chapters we describe some of the ways expanded awareness appears in our lives, giving us glimpses of our unrealized potential in consciousness.

“Experiencing God Directly: Spirituality without Religion” is an extract from The Heart of the Mind by Jane Katra & Russell Tarrg. Published by White Crow Books, it is available from Amazon and other bookstores.

http://whitecrowbooks.com/books/page/the_heart_of_the_mind/

|