|

By Michael Tymn

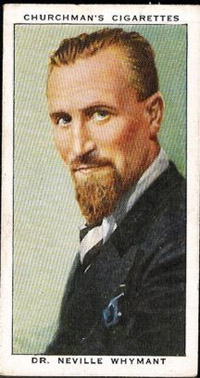

When he and his wife were invited to the New York City Park Avenue home of Judge and Mrs William Cannon for a dinner party during October 1926, Dr Neville Whymant, (below) a professor of linguistics at Oxford and London Universities, had no idea that he would be attending a séance with American direct-voice medium George Valiantine.

Mrs Cannon explained to Whymant that she feared he would decline the invitation if she had told him what was going to take place. She further explained that she needed someone with knowledge of Oriental languages to do some interpreting as what seemed to be a Chinese-speaking spirit had been breaking in at prior sittings with Valiantine.

Whymant, who spoke 30 languages, was in the United States to study the languages of the American Indian. While having no interest in Spiritualism and being somewhat skeptical, Whymant felt obligated to remain for the sitting.

‘There was no appearance or suspicion of trickery,’ Whymant recorded in his 1931 book, Psychic Adventures in New York, ‘but I mention these things to show that I was alert from the beginning, and I was prepared to apply all the tests possible to whatever phenomena might appear.’

As soon as the lights were turned off, the group recited the Lord’s Prayer and then sacred music was played on a gramophone. Voices came through for other sitters before Mrs Whymant’s father communicated in his characteristic drawl, reminiscent of the West County of England. The group then heard the ‘sound of an old wheezy flute not too skillfully played.’ It reminded Whymant of sounds he had heard in the streets of China.

When the flute-like sound faded, Whymant heard a ‘voice’ directed at him through the trumpet say in an ancient Chinese dialect: ‘Greeting, O son of learning and reader of strange books! This unworthy servant bows humbly before such excellence.’

Whymant responded in more modern Chinese: ‘Peace be upon thee, O illustrious one. This uncultured menial ventures to ask thy name and illustrious style.’

The ‘voice’ replied: ‘My mean name is K’ung, men call me Fu-tsu, and my lowly style is Kiu.’

Whymant recognized this as the name by which Confucius was canonized. Not certain that he heard right, Whymant asked for the voice to repeat the name. ‘This time without any hesitation at all came the name K’ung-fu-tzu,’ Whymant wrote. ‘Now I thought, was my opportunity. Chinese I had long regarded as my own special research area, and he would be a wise man, medium or other, who would attempt to trick me on such soil. If this tremulous voice were that of the old ethicist who had personally edited the Chinese classics, then I had an abundance of questions to ask him.’

At that point, the ‘voice’ was difficult to understand and Whymant had to ask for repetition. ‘Then it burst upon me that I was listening to Chinese of a purity and delicacy not now spoken in any part of China.’ Whymant came to realize that the language was that of the Chinese Classics, edited by Confucius 2,500 years earlier. It was Chinese so dead colloquially as Sanskrit or Latin, Whymant explained. ‘If this was a hoax, it was a particularly clever one, far beyond the scope of any of the sinologues now living.’

Apparently the communicating spirit recognized that Whymant was having a difficult time understanding the ancient dialect and changed to a more modern dialect. Whymant wondered how he could test the voice and remembered that there are several poems in Confucius’ Shih King which have baffled both Chinese and Western scholars. Whymant addressed the ‘voice’: ‘This stupid one would know the correct reading of the verse in Shih King. It has been hidden from understanding for long centuries, and men look upon it with eyes that are blind. The passage begins thus: Ts’ai ts’ai chüan êrh…’

Whymant had recalled that line as the first line of the third ode of the first book of Chou nan, although he did not recall the remaining 14 lines. The ‘voice’ took up the poem and recited it to the end.

The ‘voice’ put a new construction on the verses so that it made sense to Whymant. It was, the ‘voice’ explained, a psychic poem. The mystery was solved. But Whymant had another test. He asked the ‘voice’ if he could ask for further wisdom.

‘Ask not of an empty barrel much fish, O wise one! Many things which are now dark shall be light to thee, but the time is not yet…’ the ‘voice’ answered.

Whymant addressed the ‘voice’: ‘In Lun Yü, Hsia Pien, there is a passage that is wrongly written. Should it not read thus…?

Before Whymant could finish the sentence, the ‘voice’ carried the passage to the end and explained that the copyists were in error, as the character written as sê should have been i, and the character written as yen is an error for fou.

‘Again, all the winds had been taken out of my sails!’ Whymant wrote, pointing out that the telepathic theory, i.e., the medium was reading his mind, would not hold up since he was unaware of the nature of the errors.

There were several additional exchanges between Whymant and Confucius before the power began to fade. Confucius closed with: ‘I go, my son, but I shall return… Wouldst thou hear the melody of eternity? Keep then thy ears alert…’

Whymant attended 11 additional sittings, dialoguing with the ‘voice’ claiming to be Confucius in a number of them. At one sitting, another ‘voice’ broke in speaking some strange French dialect. Whymant recognized it as Labourdin Basque. Although he was more accustomed to speaking Spanish Basque, he managed to carry on a conversation with the ‘voice.’

‘Altogether fourteen foreign languages were used in the course of the twelve sittings I attended,’ Whymant concluded the short book. ‘They included Chinese, Hindi, Persian, Basque, Sanskrit, Arabic, Portuguese, Italian, Yiddish, (spoken with great fluency when a Yiddish- and Hebrew-speaking Jew was a member of the circle), German and modern Greek.’

Whymant also recorded that at one sitting, Valiantine was carrying on a conversation in American English with the person next to him while foreign languages were coming through the trumpet. ‘I am assured, too, that it is impossible for anyone to ‘throw his voice,’ this being merely an illusion of the ventriloquist,’ he wrote.

Not being a Spiritualist or psychical researcher, Whymant did not initially plan to write the book. However, tiring of telling the story so many times, he agreed to put it in writing, asking that with the publication of the book that others not ask him to tell the story again.

|