Deathbed Phenomena in Hospice Care

Posted on 20 April 2015, 10:04

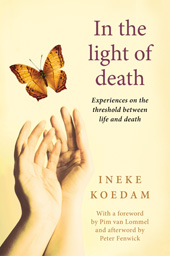

After reading Ineke Koedam’s recently-released book, In the Light of Death, I am rethinking my somewhat negative ideas about hospices. As indicated by a couple of prior posts, the last one being on January 25, 2011 (Do hospices promote despair?), I had come to the conclusion, admittedly based on very limited sampling, that hospices discourage any discussion of spiritual matters, especially the whole idea of life after death. While attending a weekend of hospice training, I was informed that spiritual matters were not to be discussed with residents unless they brought it up and then it was something that should be referred to the hospice chaplain. Prior to that training, I had attended a lecture in another state by an experienced hospice worker in which she talked all about the need for hospice residents to “live in the present.” The speaker had absolutely nothing to say about the possibility that consciousness will survive death and that the dying person’s doom and gloom might be better dealt with by discussing such survival.

Perhaps hospice policies vary from one country to another, or possibly from state to state or individually within that country or state. Koedam (below) served on the staff and as a volunteer at hospice De Vier Vogels in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and at other hospices in that country. In the book’s Introduction, she states that she attended a symposium dealing with near-death experiences in 2009, the key speakers being Doctors Pim van Lommel and Peter Fenwick, two world-renowned authorities in the field. That prompted her to carry out a small-scale study into deathbed phenomena in the Netherlands between 2009 and 2011, one in which she interviewed a number of hospice caregivers. She forewarns the reader that her book does not offer scientific statistics, “but real experiences and observations of hospice staff who work on the boundary between life and death.”

It is not uncommon, Koedam states, for dying people, in the days or weeks before death, to talk about visits from deceased loved ones. “They say that these individuals have come to collect them, or to help them to let go of life,” she explains, pointing out that many people are reluctant to talk about such experiences because they are afraid of being seen as confused and then required to take medication they don’t want. Also, some of the hospice staff avoid talking about them as they do not want to appear unprofessional. Relatives often shy away from discussing such things for fear of ridicule.

“Those people who are nearing the end find it easy to transit to and from other realities and describe other worlds,” she continues. “They talk about going on a journey, suddenly stare at a particular point in the room or turn toward the window and express feelings of surprise, joy, or wonder.”

Koedam says that the difference between a genuine “end-of-life experience” (ELE) and a drug-induced hallucination is fairly obvious. The latter are irritating and annoying and often involve very weird visions, such as insects crawling on the wall or devils dancing, but the true ELE occur mostly when the person is fully aware. They are comforting experiences that seem to help them let go of the physical world.

One caregiver explained that the dying are often somewhere else for a short while and then they come back. “You can see it in their eyes. Sort of looking, but not seeing. They look through you.” She further described it as a peaceful, serene, and beautiful atmosphere. A music therapist named Hilly told Koedam that while playing the harp for people about to transition she could clearly see them going in and out of their bodies.

A hospice volunteer told Koedam about a dying woman who told her that her body wanted to die but it couldn’t because her spirit was not yet ready. At other times, her spirit was ready but her body wasn’t. The woman explained that when her body and spirit arrived at the threshold together, then she would depart.

According to Koedam, many hospice caregivers continue to feel a presence in the room after the person has physically died. The dying “process,” she says, can take a few moments or several days. While the atmosphere is often one of love, peace, and calm, they are not always pleasant. Some caregivers are more sensitive to these “energies” than others. “Some people leave very quickly, others linger,” one caregiver reported. The usual policy at one hospice is to wait for one day before calling the funeral director to collect the body.

Some people really want to talk about death and ask the caregiver for her or his thoughts as to what to believe. “Sharing your thoughts can be very comforting and can help them to get in touch with their own beliefs,” Koedam concludes. “Sharing your own faith is not the same as evangelism. Evangelism is imposing one’s own beliefs on someone else, but sharing your own beliefs is being open about what you believe in, while at the same time being prepared to listen to the other’s point of view.”

The bottom line is that, properly understood, deathbed phenomena can offer comfort to the dying person and help him or her prepare for “transition” while also providing some peace of mind for the relatives and friends of the dying person.

After reading the chapter dealing with the “lingering presence” after physical death, I took time out to check my mail and found a new comment at an old blog I wrote about “soul mist” (see blog of June 11, 2012). A reader found it strange that this mysterious vapor or mist sometimes witnessed by people at deathbeds as the person dies is not witnessed more often. I wondered if the answer to that question might be that it is more obvious with people who leave their bodies immediately and less obvious with people who linger around their bodies, the “soul mist” just slowly oozing out and therefore less dense and less transparent. As Koedam puts it, that “something” dissipates or slowly lets go.

Other metaphysical references on this subject suggest that few souls make an immediate departure, most lingering for a time. The reader might take note of the many comments left at the June 11, 2012 blog and an earlier blog on October 4, 2010 by people who claim to have observed such soul mist.

In the light of death: Experiences on the Threshold Between Life and Death is published by White Crow Books and is available on Amazon and all good online bookstores.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die is published by White Crow Books. His latest book, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife is now available on Amazon and other online book stores.

His latest book Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I is published by White Crow Books.

Next blog post: May 4

Read comments or post one of your own

|

Was President Lincoln a Believer or an Infidel?

Posted on 07 April 2015, 12:55

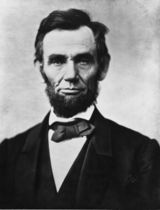

As April 15 will mark the 150th anniversary of the physical death of President Abraham Lincoln, (below) it seems like an appropriate time to examine the religious beliefs of our 16th president. Historians have not been able to agree as to those beliefs. He has been characterized as everything from a God-fearing Christian to an atheistic humanist. It seems clear that he did not often attend church services and took issue with some of the dogma, doctrine, and methods of orthodox Christianity. Nevertheless, he somehow emerges as one of our most spiritual presidents.

Lincoln was seen by many who knew him as a somber man with a gloomy disposition. In her book, The Psychic Life of Abraham Lincoln, Susan Martinez states that there was some speculation that Lincoln inherited his mother’s sadness and sensitivity, and his father’s moods, “strange spells,” and fits of solitude. Martinez examines Lincoln’s “peculiar melancholy” and the events in his life that shaped it, including his mother’s death when he was just nine, a strict and distant father, the death of a sister at age 10, and the death of his beloved Ann Rutledge when he was 26. Then, in 1850, his son Eddie, a month shy of his fourth birthday, died of diphtheria, and, 12 years later, son Willie succumbed to a typhoid-like diseases at age 11. Lincoln struggled to reconcile all of his hardships with a just and loving God.

According to Martinez, John Todd Stuart, Lincoln’s first law partner, called Lincoln an “avowed and open infidel” who went “further against Christian beliefs” than any man he had ever known. William Herndon, his junior law partner and friend, also referred to him as an “infidel.” It is said that the only book authored by Lincoln, referred to as “the little book,” apparently unpublished, questioned the infallibility of the Bible and rejected fire-and-brimstone Calvinism, while defending the idea of universal salvation. He rejected a God of wrath and punishment in favor of one of justice and loving kindness. Although his parents were Baptists, he said he preferred the Quaker beliefs of his paternal grandmother. His “little book” was burnt upon the advice of his political advisors; however, Lincoln continued to scoff at Christian clerics who pretended to be God-fearing, while not caring whether slavery was banished. Carl Sandburg quoted Lincoln as saying they “have not read their Bible aright.”

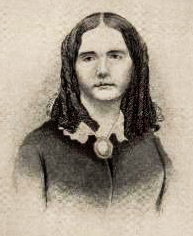

Martinez points out that more than 6,000 books have been written about Lincoln and that it has been said that “there are no important new facts to disclose.” She takes issue with that comment as the stories about Lincoln’s association with several credible mediums, especially one Nettie Colburn Maynard, (below) while not new, have been pretty much ignored, forgotten, or denied. Most of Lincoln’s biographers have deemed it below the dignity of such a great man, concluding that it never happened or that it should be swept under the rug. A number of web sites suggest that Colburn was a charlatan.

There is, however, evidence indicating that Lincoln sat with a number of mediums. It has been suggested that his wife Mary insisted on his attending séances with her after the death of their son, Willie, but there is evidence that he sat with mediums even before Willie’s death, and that he was accompanied by various members of his cabinet, including, Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War, Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy, James J. Speed, Attorney General, and Isaac Newton, Commissioner of Agriculture. Francis B. Carpenter, painter of the famous picture honoring the Emancipation Proclamation and also of Lincoln’s last portrait made from life, discussed Lincoln’s interest in spiritualism in his book, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln.

One of those earlier mediums with whom Lincoln sat was J. B. Conklin, a trance medium from Ohio. Shortly after Lincoln was elected president, an article appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in which he was attacked as a “Spiritualist.” The only thing false about the article, Lincoln was quoted, “is that the half of it has not been told. This article does not begin to tell the wonderful things I have witnessed.”

Colonel Simon P. Kase of Philadelphia, a railroad tycoon serving on the staff of the Secretary of War and close friend of Lincoln’s, claimed to have been present at the president’s sitting with Nettie Colburn. He said that it lasted a full hour and a half and that the spirit speaking through the entranced young woman dwelt strongly on the importance of the emancipation of the slaves, saying that the war could not end unless slavery was abolished. “The President listened with the greatest attention throughout her discourse,” Kase recalled. “It was a scene that would never be erased from the memory bringing to mind the passage in Scriptures where the head of the nation was being taught by babes and sucklings.” Kase added that he was fully convinced in his own mind that Lincoln was fully convinced at that point of the necessity of issuing the great Proclamation, which he had prepared well before that day but did not sign until just after the séance.

The same spirits may have been active a decade earlier when Harriet Beecher Stowe penned the popular 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book said to have been very influential in the abolitionist movement. Stowe claimed that the book was written through her, “I only holding the pen.”

Joshua F. Speed, said to be Lincoln’s best friend, quoted Lincoln as saying, “I have had so many evidences of God’s direction, so many instances when I have been controlled by some other power than my own will, that I cannot doubt that this power comes from above…I am satisfied that when the Almighty wants me to do or not do a particular thing, He finds a way of letting me know it.”

Clearly, Lincoln was not an orthodox Christian. He may not have been a card-carrying Spiritualist even if his beliefs were spiritualistic in nature, but he certainly appears to have believed in a Creator and the survival of consciousness at death. In his 1909 book, Why We Love Lincoln, James Creelman, a prominent journalist and editor, wrote: “In the upward reachings of Lincoln’s life there was a singular mysticism that sometimes startles one who contemplates the imperishable grandeur of his place in history. He saw omens in dreams and experimented with the ghostly world of Spiritualism. He predicted a violent death for himself, dreamed of his own assassination, and discussed the matter seriously, and gave evidence many times of a strange emotional exaltation, alternating with brooding sadness…but behind these eccentricities were sanity, conscience, strength, and far-seeing penetrativeness.”

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die is published by White Crow Books. His latest book, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife is now available on Amazon and other online book stores.

His latest book Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I is published by White Crow Books.

Next blog post: April 20

Read comments or post one of your own

|