Are Sports an Escape from Death Anxiety?

Posted on 22 February 2016, 10:18

Humankind cannot bear very much reality.

– T. S. Eliot

A large photo on the front sports page of The Honolulu Star Advertiser before last month’s Pro Bowl in Honolulu showed two military men obtaining the autograph of a football player. It is a scene I have witnessed a number of times over the years, one that always leaves me pondering on the seemingly insane paradox of it all. In effect, the real-life combatants are paying homage to the pretend combatants. The unreal has become the real.

To fully appreciate the situation, one has to keep in mind that sport, or athletics, developed in ancient Greece as practice for war. Pioneering psychologist William James saw nineteenth century sports as a way to develop “the manliness to which the military mind so faithfully clings.” The bottom line is that athletes are just playing war. And Society has decided that those who play war are to be revered and rewarded much more than those who really engage in it. Isn’t it strange that a football player falling on a fumbled ball, leading to a touchdown, will be heroically celebrated much more than a soldier who throws himself on a hand grenade to save his fellow combatants? Of course, it’s like that in other aspects of life as well when we consider that a movie actor is paid millions of dollars to act like an ordinary person – a person who might not make as much money in a lifetime as the actor made for pretending to be him or her in that one movie. How absurd it all seems! Our model for military heroism is John Wayne, an actor who pretended to be a soldier in a number of movies but never served a day in the military. Again, it is the unreal becoming the real.

Before the kickoff of the recent Super Bowl, military men and women – the real warriors – were on the field playing musical instruments, looking anything but warrior-like, while seemingly setting the stage for the pretend warriors to enter the arena and display valor, courage, daring, and perseverance, all those qualities so valued on the real battlefield. All the while, the real warriors continued to pursue the pretend warriors for autographs and selfies whenever the opportunity presented itself.

I admit to having been a sports fan for most of my life, since at least age 10, when I adopted the Brooklyn Dodgers as my team and Jackie Robinson, Peewee Reese, and Duke Snider as my heroes. In football, it was Johnny Lujack, Emil Sitko, and Leon Hart of Notre Dame I looked up to most. I was so avid a Dodgers fan that when they lost a game I would feel depressed the rest of the day. When they won, my “spirits” soared.

My fanaticism gradually waned with age, but I still enjoy watching a good game, even though I abhor showboating by athletes, especially end zone dances. I understand a person having a passion for sports, but there is a point at which passion turns to mindlessness and madness, when so many people are affected that our culture and way of life seem threatened with destruction.

In his book, The Joy of Sports, Michael Novak states that “the underlying metaphysics of sports entails overcoming the fear of death.” He points out that defeat hurts like death. On the other hand, “to win an athletic contest is to feel as though the gods are one’s side, as though one is Fate’s darling, as if the powers of being course through one’s veins and radiate from one’s action – powers stronger than nonbeing, powers over ill fortune, powers over death.”

As George Leonard analyzes it in his classic book, The Ultimate Athlete, risk taking and dying are at the very core of sports. The athlete pushes himself (or herself) to a boundary he cannot cross. “We need no roundabout theories to explain the fascination of death and the salutary effects of calculated risk,” he writes. “We simply must remember that, from the standpoint of embodied consciousness, death provides us our clearest connection with the eternal.” Leonard adds that in approaching the ultimate boundary, death, we undergo preparation for a larger transformation. Socrates called it “practicing death.” Almost always at an unconscious level, it is learning as much about death now so as to facilitate the transition in the future. It is a paradox in itself – both embracing death and avoiding it.

I “practiced death” for many years in the sport of middle- and long-distance running (see below), although I didn’t fully grasp at the time that the finish line represented death. To borrow from Sir Roger Bannister, I recall the finish line looming ahead like “a haven of peace after the struggle.” As Bannister saw it, the greatest part was yet to come – liberation! “No words could be invented for such supreme happiness, eclipsing all other feelings,” he recalled breaking the four-minute mile barrier, adding that he felt bewildered and overpowered.

“To run, to fall, to merge, to die: such passionate language makes us uncomfortable,” Leonard states. “We are embarrassed by that which stands at the very heart of the Game of Games. We seek comfort in forgetfulness. We shrink from the inevitability of death.”

If cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker were still alive, I suspect he would view the recent Super Bowl as one gigantic escape from death anxiety. In his 1973 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Denial of Death, Becker asserted that death is the mainspring of human activity. “The idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else,” he offered, going on to explain that to free oneself of death anxiety almost everyone chooses the path of repression. That is, we bury the anxiety deep in the subconscious and go about our everyday activities mostly oblivious to the fact that in the great scheme of things those activities are exceedingly short term and for the most part meaningless. Borrowing from the existentialist Søren Kierkegaard, Becker said that man, in his flight from death, becomes a “Philistine.” For Kierkegaard, Phistinism was man tranquilizing himself with the trivial. It is man striving to be one with his toys and his games. Many people, Kierkegaard opined, are so tranquilized in the mundane or the trivial that they lack the awareness that they are in despair.

“Sport is death-free play, and games shut out death,” writes humanist philosopher Alan Harrington in his book, The Immortalist. “We have the commonly recognized but still quite amazing circumstance that for masses of people around the world the outcome of football, baseball, soccer, basketball and boxing matches can sometimes be far more important than actual wars and revolutions.” As Harrington saw it, the madness of the spectators and the dedication of the players can best be understood by viewing the games as man-made immortality rites. “The stadium turns into a pit of the gods in which heroes fight to become divine,” he explains. “And trailing behind them come the legions – all of us fans and spectators – who derive our being, our excellence, and our own worthiness to be converted into gods from the performance of our heroic representatives.”

It is one thing for an athlete to unconsciously “practice death” in a particular arena, but quite something else for those not participating in the game to vicariously join in the death-embracing or death-avoiding activity, however it is interpreted. Based on the fanaticism, mindlessness, and madness we witness with such gala events as the Super Bowl, it does seem that the masses have been brainwashed by the media into thinking the game is really important. We might call it a “flight from reality,” one apparently brought about by television, consumerism, the isolation of modern living, and the trend toward nihilism. The Super Bowl might be seen as an excuse for people to congregate and share in the despair and insecurity they feel in their everyday lives, though many of them might not realize, as Kierkegaard suggested, that they are in despair. It is an escape from death anxiety. There is strength in numbers and the spectators feel something of a “oneness” as they worship the players, their new gods, and root for one of the teams to emerge victorious, thereby somehow cheating death. If victory is achieved, they live on, but if defeat is the outcome, the mindset seems to be: let’s all get drunk, hold hands, and march into the abyss of nothingness, the pit of extinction, together.

“Celebrity culture is, at its core, the denial of death,” writes Chris Hedges, another Pulitzer Prize winner, in his book Empire of Illusion. He goes on to say that religious beliefs and practices are commonly transferred to the adoration of celebrities and that a certain emptiness follows. Hedges devotes several pages to the appeal of professional wrestling, but the same might be said of professional football. “These ritualized battles give those packed in the arenas a temporary, heady release from mundane lives. The burden of real problems is transformed into fodder for a high-energy pantomime…. For most, it is only in the illusion of the ring that they are able to rise above their small stations in life and engage in a heroic battle to fight back.”

I like the way David Awbrey expresses it in his book, Finding Hope in the Age of Melancholy: “The culture no longer inspires society, and the bonds of shared experience that once held people together are reduced to TV, pro sports, and plotless but visually spectacular computer enhanced movies. Unless Americans regain a broad purpose in life, they will remain secluded within their corporate cubicles, sending binary bytes into a cybernetic mist, or sequestered in their living rooms, watching moronic sitcoms in the dark.” And, I might add, real combatants will continue to pay homage to pretend combatants.

Broad purpose in life? Can there be any purpose other than seeing this life as preparation for a much larger life?

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die is published by White Crow Books. His latest book, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife is now available on Amazon and other online book stores.

His latest book Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I is published by White Crow Books.

Next blog post: March 7

Read comments or post one of your own

|

Ectoplasm & Advanced Spirit Communication Explained

Posted on 08 February 2016, 10:49

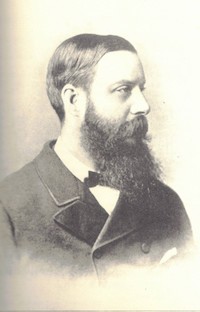

Soon after William Stainton Moses, (below) an Anglican priest and English Master at University College, London, discovered his mediumistic ability in 1872, he and Dr. Stanhope Speer, his good friend, experienced a cloud of luminous smoke, very phosphorus like, that very much alarmed them. The next night, Moses asked the controlling spirit, an entity calling himself Mentor, one of the band of 49 spirits operating in the group headed by a spirit calling “itself” Imperator, what it was all about. The following dialogue took place, as recorded by Dr. Speer:

Mentor: “We are scarcely able to write. The shock has destroyed your passivity. It was an accident. The envelope in which is contained the substance which we gather from the bodies of the sitters was accidentally destroyed, and hence the escape into outer air, and the smoke which terrified you. It was owing to a new operator (spirit operator) being engaged on the experiment. We regret the shock to you.”

Moses: “I was extremely alarmed. It was just like phosphorus.”

Mentor: “No, but similar. We told you when first we began to make the lights that they were attended with some risk; and that with unfavourable conditions they would be smoky and of a reddish yellow hue.”

Moses: “Yes, I know. But not that they would make a smoke and scene like that.”

Mentor: “Nor would they, save by accident. The envelope was destroyed by mischance, and the substance which we had gathered escaped.”

Moses: “What substance?”

Mentor: “That which we draw from the bodily organisms of the sitters. We had a large supply, seeing that neither of you had sustained any drain of late.”

Moses: “You draw it from our bodies – from all?”

Mentor: “From both of you. You are both helpful in this, both. But not from all people. From some the substance cannot be safely drawn, lest we diminish the life principle too much.”

Moses: “Robust men give it off?”

Mentor: “Yes, in greater proportion. It is the sudden loss of it and the shock that so startled you that caused the feeling of weakness and depression.”

Moses: “It seemed to come from the side of the table.”

Mentor: “From the darkened space between the sitters. We gathered it between you in the midst. Could you have seen with spirit eyes you would have discovered threads of light, joined to your bodies and leading to the space where the substance was being collected. These lines of light were ducts leading to our receptacle.”

Moses: “From what part of my body?”

Mentor: “From many; from the nerve centers and from the spine.”

Moses: “What is this substance?”

Mentor: “In simple words, it is that which give to your bodies vitality and energy. It is the life principle.”

Moses: “Very like sublimated phosphorus?”

Mentor: “No body that does not contain a large portion of what you call phosphorus is serviceable to us for objective manifestations. This is invariable. There are other qualities of which you do not know, and which not all spirits can tell, but this is invariable in mediums for physical manifestations.”

On another occasion, Imperator communicated: “We have a higher form of what is known to you as electricity, and it is by that means we are enabled to manifest, and that Mentor shows his globe of light. He brings with him the nucleus, as we told you.”

On August 10, 1873, Dr. Speer recorded that Mentor said he would show his hand. “A large, very bright light then came up as before, casting a great reflection on the oilcloth, came up as before in front of me; inside of it appeared the hand of Mentor, as distinct as it can well be conceived. ‘You see! You see!’ said he, ‘that is my hand; now I move my fingers,’ and he continued to move his fingers about freely, just in front of my face. I thanked him for his consideration.”

At a sitting on September 11, 1873, Mrs. Speer recorded: “....the next evening we sat again in perfect darkness, which Mentor took advantage of, as he showed lights almost as soon as we were seated. He then controlled the medium (Moses), talking to us about the lights as he showed them. At first they were very small. This, he said, was the nucleus of light he had brought with him, a small amount of what we should call electricity. This nucleus lasted all the time, and from the circle he gathered more light around it, and kept it alive by contact with the medium. At one time, the light was as bright as a torch. Mentor moved it about all over the table and above our heads with the greatest rapidity.”

Imperator claimed to be from the Seventh Sphere and said that his real name would mean nothing to Moses or the others, nor would the real names of Mentor, Rector, Prudens, Minister, and Doctor, all members of the “band of 49.”

At a later sitting, Prudens, Doctor, and Minister, in a group communication, explained: “The higher spirits who come to your earth are influences or emanations. They are not what you describe as persons, but emanations from higher spheres. Learn to recognize the impersonality of the higher messages. When we first appeared to this medium he insisted of our identifying ourselves to him. But many influences come through our name. Two or three stages after death, spirits lose much of what you regard as individuality and become more like influences. I have now passed to the verge of the spheres from which it is impossible to return to you. I can influence without any regard to distance. I am very distant from you now.”

Another member of the band of 49, Elliotson, added: “The exalted spirit, Imperator, who directs this medium (Moses), bathes me in his influence. I do not see him, but he permeates the space in which I dwell. I have received his commands and instructions, but I have never seen him. The medium sees a manifestation of him, which is necessary in his case, not in mine. The return to earth is a great trial for me. I might compare it to the descent from a pure and sunny atmosphere into a valley where the fog lingers. In the atmosphere of earth I seem completely changed. The old habits of thought awaken, and I seem to breathe grosser air.”

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die is published by White Crow Books. His latest book, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife is now available on Amazon and other online book stores.

His latest book Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I is published by White Crow Books.

Read comments or post one of your own

|