|

|

|

|

Surgeon says Mortality can be a Horror for the Dying

Posted on 25 September 2017, 10:41

In his best-selling book, “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End,” Dr. Atul Gawande, a surgeon and a professor at Harvard Medical School, discusses the failure of medicine to effectively deal with the needs of the aging and dying. “Our reluctance to honestly examine the experience of aging and dying has increased the harm we inflict on people and denied them the basic comforts they most need,” he offers in the Introduction. “Lacking a coherent view of how people might live successfully all the way to their very end, we have allowed our fates to be controlled by the imperatives of medicine, technology, and strangers.”

In effect, the first part of the book is about the needs of the elderly as they struggle with the three plagues of nursing home existence – boredom, loneliness, and helplessness, while the second half of the book deals with the needs of the terminally ill, especially the need for them to face up to their ultimate demise without total despair. “The only way death is not meaningless is to see yourself as part of something greater: a family, a community, a society,” Gawande concludes from his talks with many aging and dying people, including family and patients. “If you don’t, mortality is only a horror.”

If I am properly interpreting Gawande’s conclusions, it’s the same old plan many others have espoused – live for today, enjoy the grandchildren and the friendships, savor the little pleasures, identify a purpose outside of ourselves, and overall disregard the words of poet Dylan Thomas that we should “not go gentle into the good night.” In other words, do not rage against death, but accept it as part of life’s journey.

It all sounds so simple and idealistic, but it has been my experience and observation over 80 years of living and seeing many friends and family depart earthly existence that it doesn’t work, at least for a thinking person. The fact is that nearly all the daily pleasures we experience are for the most part mundane and ordinary, whether reading a novel, painting a landscape, viewing a movie, watching a sporting event, shopping, playing a game of chess or checkers, or just smelling the roses. So much of our time is spent escaping from reality in fiction and the pretend wars of the athletic arena. In the great scheme of things, how can any of it really matter to a person on death’s threshold?

How often can one meet with friends and discuss commonplace things? What do they talk about – the weather, sports, politics? As Sophia suggested to her three housemates on the Golden Girls, their best talks had to do with trashing other people. Considering the fact that politics is a means to an end – an end the dying person won’t be around to witness – is such a discussion anything more than a distraction? And how many grandchildren really want their old-fogey grandparents hanging around and interrupting their more “important” social media discourse? Pray tell, Dr. Gawande, what daily “pleasures” can we truly savor if we believe we will be extinct in a matter of days or weeks? Let’s be realistic.

As I suspected before reading the book, Gawande avoids the most important subject facing the aging and dying, one that can give hope and a light through the darkness – the survival of consciousness at death, or, for the true skeptic, the possible survival of consciousness at death. The subject is too unscientific and involves too much religious superstition for all except the most courageous men and women of science to even allude to. It calls for living in the future rather than enjoying the present, seemingly a contraindicated approach. Gawande’s credibility as a professional man of medicine might very well have been compromised had he dealt with such a “foolish” subject.

To be fair, Gawande does touch upon it in the Epilogue of the book, mentioning that his father, also a physician, wanted some of his ashes spread on the Ganges River in India, which is sacred to all Hindus, as this supposedly assures eternal salvation. “I was not much of a believer in the idea of gods controlling people’s fates and did not suppose that anything we were doing was going to offer my father a special place in any afterworld,” Gawande states, making it clear that he was simply carrying out his father’s wishes and performing a ritual that both his mother and sister wanted.

I applaud Dr. Gawande’s efforts to effect a change in being more accepting of death and not raging against it as Dylan Thomas would have us do, but I don’t think he said anything more than Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross said in her 1969 classic On Death and Dying, or for that matter as much as Dr. Stephen J. Iacoboni offers in his 2010 book, The Undying Soul. “Never did we look for or try to save the soul of our patients,” Iacoboni, an oncologist, laments. “We were supposedly among the most brilliant medical investigators in the world, and yet we had no knowledge of or interest in that which mattered most.”

Like Gawande, Iacoboni found that many of his patients had unrealistic expectations and didn’t want their hopes dashed. They pleaded for or demanded a cure. While trying not to extinguish what little hope there might have been, Iacoboni tried to be more honest with them than other doctors. Most of the terminal patients were, however, unable to accept the truth of their condition and lived their remaining days in a state of despair.

In rating Iacoboni’s book over Gawande’s, I can only conclude that I must not be a very good judge of such books, since Iacoboni’s book never approached the best-seller list and has only 14 reader reviews at Amazon.com, compared with 6,540 reviews for Gawande’s book.

If I were to have the opportunity and privilege to talk one-on-one with Dr. Gawande, my lack of credentials not withstanding, I would suggest to him that he completely dismiss any ideas he has about the afterlife of orthodox religions and consider all that psychical research, near-death studies, and other consciousness studies have given us over the past 170 years. If he approaches the subject with an open mind and with proper discernment, he should find strong evidence turned up by some very distinguished scientists and scholars that prima facie establish that we all have energy bodies, or spirit bodies, that survive death. Moreover, he should be able to conclude that we have no a priori reason for believing that the physical world is the only world. With that in mind, he should be able to see at least the possibility – a strong possibility if the cumulative evidence is fully grasped – of a larger life and the hope that it can give to the dying as they deal with death anxiety. In all that he will find his “coherent view.”

Assuming that Gawande had the patience to hear me this far, I would anticipate that he is aware of the usual theories offered by the fundamentalists of science to debunk the evidence as resulting from either trickery, unconscious deception, or not-well understood workings of the subconscious mind, and that he would then excuse himself and return to his important work. If, however, he remained and showed any interest, I would quote the words of the great physicist Sir Oliver Lodge: “Science is incompetent to make comprehensive denials about anything. It should not deal in negatives. Denial is no more fallible than assertion. There are cheap and easy kinds of skepticism, just as there are cheap and easy kinds of dogmatism.”

I would tell Gawande that if he is able to remove the mental blocks of scientific fundamentalism, he should be able to see that our consciousness is attached to those energy bodies and that it survives death in a much more meaningful way than that suggested by orthodox religions. He will have to recognize that much of it is beyond modern mainstream science and look for a preponderance of evidence rather than absolute certainty. If he really digs into it and closely examines the arguments of the debunkers rather than just accepting them because they more easily fit into a materialistic paradigm, he might even find evidence that goes beyond a reasonable doubt, more than enough to give hope to all those patients in despair who expect obliteration of the personality or, even worse, an eternity of floating around on clouds, strumming harps, and singing praises to a self-centered, cruel and capricious god.

If Dr. Gawande thinks that is all too much for him to accept, I would urge him to carefully consider how inadequate his recommendation for dealing with death anxiety are, something he might not fully appreciate until he is a little older, and I would once more point to the advice of pioneering psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, who said that “a man should be able to say he has done his best to form a conception of life after death, or to create some image of it – even if he must confess his failure.” Not to do so, Jung added, is “a vital loss.” I would further ask that he also carefully consider Dr. Jung’s words that “while the man who despairs marches toward nothingness, the one who has placed his faith in the [survival] archetype follows the tracks of life and lives right into his death. Both, to be sure, remain in uncertainty, but the one lives against his instincts, the other with them.” I’d ask Gawande to explain why he thinks Jung was wrong in making such proclamations, but he would likely shrug it off and say it is a matter of opinion, not a matter of science.

If Gawande really believes that “living in the moment” and savoring all those mundane activities is an effective way to deal with death anxiety and its concomitant despair, there would be no point in going on with the discussion. Perhaps there are some out there who have mastered the ability to repress all ideas of death as they march toward what they see as an abyss of nothingness, but I don’t recall having met any such person. I have met some who claim they have no fears of falling into that abyss, but, although I can’t be certain, it does come across to me as nothing more than bravado, i.e., false courage. And if the good doctor were to further suggest that discussing the larger life is best left to ministers and hospital chaplains, I would take issue with him on that and point out that orthodox religions are stuck in the muck and mire of dogmatism and therefore have for the most part not been open to the discoveries of valid scientific research relating to an energy or spirit body. I’d admit that such science is not exact science, but neither is medicine anywhere close to being an exact science. Why accept the inexactitudes of medicine and not of controlled research in psychic matters? Is it simply hubris?

I’d argue that “meaning” is not the strict domain of religion, that religion arises out of the existential search for meaning, and that science can make its own search in that regard, which it has done, even if not fully appreciated by the masses. I’d end my discussion by calling upon another Harvard professor of some reputation, a pioneer in the field of psychology, William James.

To quote Professor James: “Let sanguine healthy-mindedness do its best with its strange power of living in the moment and ignoring and forgetting, still the evil background is really there to be thought of, and the skull will grin in at the banquet. In the practical life of the individual, we know how his whole gloom or glee about any present fact depends on the remoter schemes and hopes of which it stands related. Its significance and framing give it the chief part of its value. Let it be known to lead nowhere, and however agreeable it may be in its immediacy, its glow and guilding vanish. The old man, sick with an insidious internal disease, may laugh and quaff his wine at first as well as ever, but he knows his fate now, for the doctors have revealed it, and the knowledge knocks the satisfaction out of all these functions. They are partners of death and the worm is their brother, and they turn to a mere flatness.”

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Next blog post: October 9

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

A New ‘Number One’ Book on the Afterlife.

Posted on 11 September 2017, 8:52

In my blog post of December 5, 2016, I listed my “Top 30” old books – those published before 1950. At the time, I thought that I’d read every significant book before 1950. However, I missed one, The Survival of the Soul and Its Evolution After Death, authored by Pierre-Emile Cornillier and first published in 1921. That book is now number one on my list. It seems to have impressed publisher Jon Beecher, as well, as his White Crow Books has just recently republished it.

It wasn’t until a few months ago when, while searching in one of Dr. Robert Crookall’s books for some information on a particular subject matter, that I became aware of the book. I noted that Crookall, a botanist and geologist who authored 14 books on psychical matters during the 1950s and ‘60s, named it as his favorite. I found a rare copy and plunged into it.

Books by William Stainton Moses and Allan Kardec offer much as to how the spirit world works, but I think Cornillier has outdone even them with this book. Why it has not survived as a classic in the field, as their books have, is a mystery to me. My attempts to find anything to discredit Cornillier have turned up nothing.

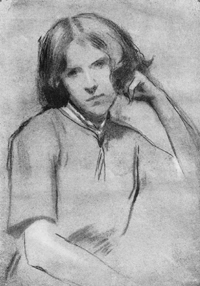

Cornillier (1862 – 1942?) was a French artist who had an interest in psychical research when, in 1912, he realized that Reine, an 18-year-old model (below) he had been employing for several months, had psychic abilities of some kind. He soon began some experiments with her and when she was in a “hypnotic sleep” she was able to go out of body and report on things and happenings in other places. Cornillier, who clearly had a very discerning mind, was able to confirm many of Reine’s out-of-body observations. Further experimentation involved communication with some apparently low-level spirits, but a “high spirit” named Vettellini emerged in the ninth séance and continued on as Reine’s primary guide through 107 séances documented by Cornillier.

The 107th séance was on March 11, 1914, but the publication of the book was delayed by the Great War, which began several months later, an event that Vettellini continually warned Cornillier about. “Neither the war, nor the interior trouble can be averted,” Vettellini communicated on June 2, 1913, more than a year before the outbreak of WWI. “The Spirits are doing all in their power to mitigate this most appalling catastrophe, but the storm is there; it is almost upon us; it is bound to burst. It will be delayed; but it is inevitable. 1913 was the date…By dint of infinite precautions and compromises, time will be gained. But to what avail? A simple gesture and the evil will be let loose.”

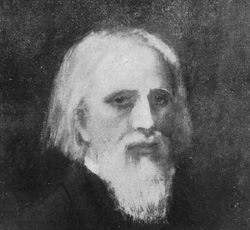

Cornillier put numerous questions to Vettellini, (below) including the nature of the spirit body, how spirits awaken on the other side, what they look like, their faculties, grades of consciousness among spirits, activities in the spirit world, spirit influence on humans, God, reincarnation, astral travel, difficulties in communication by high spirits, deception by inferior spirits, premonitions, dreams, time, space, animal spirits, materializations, apparitions, cremation, and other concerns that he had about how things work in the spirit world.

“Death is predetermined,” Vettellini communicated in one sitting. “Sickness and accident are means used by the Spirit-directors for the accomplishment of destiny. Life sometimes defends itself vigorously against Death, particularly in the case of inferior beings who intuitively dread the mystery. But Spirit-messengers are there, awaiting the release of the soul, and when the hour comes, aid and, if need be, force the escape. The soul is then conducted before an assembly of high Spirits – the white ones – who recognize the degree of evolution. If this evolution is slight, the soul will wander about in our atmosphere for a longer or shorter period, reviewing his earthly life, taking cognizance of his responsibilities and learning to develop his own conscience by observing, from the other side, the struggle of living beings. In all this he will at first be guided by the higher Spirits; then alone, or surrounded by those of his own evolution, he will wander through space – indifferently, lamentably or joyfully, as his level determines – until the moment, more or less remote, when the Spirit-directors will send him back to Earth again for a new incarnation, for another beneficent experience. If the disincarnate soul has already attained a superior evolution, he may become a Spirit-director himself, or he may voluntarily accept another reincarnation for a definite purpose – a sacrifice that will carry him on still higher in the scale of evolution.”

Vettellini often responded to Cornillier by telling him that the various modes of life in the spirit world are beyond human comprehension as their concepts do not exist on our plane. Reine told Cornillier that she understood everything that Vettellini said while she was in the trance state, but, even though she recalled some of them upon returning to her body, she had no words to explain them.

As Cornillier came to understand, the more evolved spirits were at too high a vibration to effectively communicate with humans and therefore usually relayed their messages through less evolved spirits, whose vibration was closer to the human vibration. These lower spirits then relayed the messages through the medium. However, the messages were often misinterpreted by the lower spirits and/or by the medium, or they were colored by the medium’s subconscious based on her experience or ideas. “Reine – and this must not be forgotten – does not hear in words the substance of what she repeats,” Cornillier explained. “She translates into words the vibrations that convey Vettellini’s thought, and as her education is extremely meager, and her vocabulary limited, her interpretations may occasionally be inexact. Conscious of her difficulties, Vettellini, in certain cases, gives her the precise words, which she then repeats to me mechanically, without comprehending. And this is another source of error. The rectification is always made in a following séance, but sometimes long after; for, oftener than not, it is an unexpected question which reveals that the transmission has been imperfect.”

Cornillier’s deceased father and grandfather communicated with him, and his wife received evidential communication through an old friend. What was especially evidential to Cornillier, however, was that Reine was a “simple child” in her conscious state, with no prior knowledge of the things she related in some detail and without hesitation in the trance state. Of this as well as her sincerity and integrity he had absolutely no doubt.

In the 60th sitting, Cornillier asked if everyone has spirit guides. “Yes, generally speaking, each person living has one or more Spirit-friends,” Vettellini replied. “But not everyone is able to keep his friends. Often they are rebuffed and discouraged by your incomprehension, or your bad instincts, which attract lower Spirits around you. Each one creates his own astral society; he has around him the friends whom he merits. As a rule, if a Spirit is to remain the constant protector of an incarnated being, that being must be in the same current of evolution and not too inferior to his Guide; otherwise he could not fall under the influence of the latter nor comprehend his inspiration.”

In his 42nd sitting, Cornillier asked Vettellini whether the individual consciousness becomes absorbed in a universal consciousness as spirits evolve or whether they retain their individuality. “Monsieur Corniller, Vettellini affirms that individual consciousness can but grow greater and greater as evolution progresses,” Reine relayed. “All that is gained and conquered by a being, defines and strengthens his individuality. It is his, – and for himself. The blue spirits are more individual than the grey; the white spirits more individual than the blue; and above the white, the still higher Spirits are still more themselves.” (Vettellini had previously explained that lower level spirits are seen as red in color, the more advanced as blue, and those above them as white.)

In a later sitting, Cornillier asked why men of great stature on earth do not manifest themselves after death to give decisive proof of their survival. “Men of great value on earth – conscientious students, authorities in their specialties – are not necessarily Spirits of high evolution,” Vettellini responded, going on to explain that some of them have a difficult time coming to grips with their lack of importance in the spirit world. He further explained the people with fixed ideas – including religious fundamentalists and the so-called “intellectual elite” of the world who deny psychical phenomena – are generally not highly evolved beings. When they transition after death to the astral world, they cling to their old ideas and since they are better able to influence those still in the earth realm than more evolved spirits, progress in evolution is obstructed.

In his Conclusion, Cornillier recognizes that his book will not appeal to the “scoffers,” as his faith in Reine’s character was such that he “refrained from establishing a so-called scientific control over my medium.” He points out that scientists of the highest reputations have taken every possible precaution, and yet their skeptical peers have questioned their methods and objectivity while heaping abuse upon them.

I recommend that the reader begin with the Conclusion of the book in order to get a feel for Cornillier’s intelligence, if not brilliance, and his scientific acumen. Be prepared to be overwhelmed, and if you know someone approaching this life’s end, pass the book on to him or her. It may very well give the dying person some hope while mitigating fears relative to death.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

The Survival of the Soul and Its Evolution After Death by Pierre-Emile Cornillier is available from Amazon

Next blog post: Sept. 25.

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

|

|