Asking God to take a back seat

Posted on 20 November 2017, 10:04

According to a recent report by the Pew Research Center, more Americans say it’s not necessary to believe in God to be moral. It goes on to explain that 56 percent of U.S. adults have this belief, up from about 49 percent who expressed this view in 2011.

People calling themselves humanists – mostly atheists who claim to subscribe to a moral code – would certainly say that it is not necessary to believe in a god to be moral. They contend that we can lead lives of love, empathy, service, morality and humility without any belief in a god or an afterlife. No doubt some of them can do so, but idealism always yields to pragmatism when it comes to the masses, when the lures of materialism become too tempting and give way to hedonism and criminal behavior. The “seven deadly sins” of religion – greed, envy, lust, pride, anger, sloth, and gluttony – kick in for the majority at some point in the pursuit of the materialistic “good life.” The same materialistic lures are also there for the theists, but many of them consider the fear of punishment in the orthodox afterlife and think twice before giving into the immoral temptations.

An argument can easily be made that the humanist who lives a life of morality is more heroic than the religionist, since his or her morality stems from a benevolent character, not from fear, but there is no reason to believe that an equal number of religionists are not acting out of benevolence rather than fear, perhaps an amalgamation of the two for some. While impossible to measure, it seems like the fear factor contributes significantly to controlling the more criminal aspects of immorality in the pragmatic world, thereby lending itself heavily to religion in its comparison with humanism as a way of regulating morality, at least from a societal viewpoint.

I am not aware of any measure or gauge to be applied to morality, as it is too subjective a word, but I think most people who have been around this realm of existence for any length of time will agree with me that our moral standards are in serious decline. I like the way Chris Hedges, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, analyzes it in his book, Empire of Illusion. “The cult of self dominates our cultural landscape,” he offers. “The cult has within it the classic traits of psychopaths: superficial charm, grandiosity, and self-importance; a need for constant stimulation, a penchant for lying, deception, and manipulation, the inability to feel remorse or guilts.” Hedges sees this decline as a result of the “celebrity culture” that has risen up around us – a culture that cannot distinguish between reality and illusion.

To fully grasp Hedges’s words we need only observe how movie stars are much more admired and better compensated than the real-life people they portray, while athletes, who are play or pretend warriors, are more respected than soldier fighting real wars. A football player who falls on a fumbled ball for a winning touchdown is more acclaimed than a combatant who falls on a grenade to save the lives of his buddies in arms.

Hedges believes that “the moral nihilism of celebrity culture is played out on reality television shows, most of which encourage a dark voyeurism into other people’s humiliation, pain, weakness, and betrayal.” The mantra for this mindset was perhaps best displayed on a television show from a few years back when the audiences chanted “Jer-ry! Jer-ry! Jer-ry!”

In his book, Why Christianity Must Change or Die, John Shelby Spong, an Episcopalian bishop, contends that we are living in a morally neutral universe. “The death of the God of theism,” he claims, “has removed from our world the traditional basis of ethics.” He adds that “Some respond with a panicked pursuit of pleasure. Some seek to escape their fears of moral meaninglessness in the world of alcohol and drugs. Some sink to the ultimate level of despair and fall into depression or even suicide. Some try to shield themselves form the unsettling sense of emptiness by becoming hysterically religious, as if shouting certain religious phrases with emotion and a feigned certainty might convince them that everything is still the way it has always been.” These are signs, Spong continues, “the signs that a loss of meaning has engulfed our world. We no longer know how to tell right from wrong, and above all else, our confusion reflects the death of the theistic God in whom all these things were once grounded.”

Earlier in the book, Spong dismisses the idea of a personal, humanlike God. “Theism, as a way of conceiving of God, has become demonstrably inadequate, and the God of theism not only is dying but is also probably not revivable,” he writes, going on to define his new God as the “Ground of all Being,” while wondering if such a God is anything more than “a philosophical abstraction serving merely to cushion our awakening into the radical aloneness of living in a godless world.”

Spong defines himself as “a believer who lives in exile,” in effect believing that there is some higher power and some purpose in life, that it is not all a march toward an abyss of nothingness, and there is a light at the end of the tunnel. He comes across as an optimistic humanist, one who is ignorant of the multitude of evidence supporting the survival of consciousness at death, a concern that does not necessarily follow a belief in God.

As churches continue to empty and the moral compass goes further south, it would appear that many have adopted the same view as Spong, unable to believe in the God of the Bible, a God who would permit bad things to happen to good people and who would be so heartless as to condemn them to everlasting punishment in a horrific hell for even small transgressions from “His” rules of conduct, a God who requires adoration, praise and worship like some egotistical king.

Considering the decline in morality and the greater acceptance of a nihilistic outlook we are now witnessing, I see reason to believe that there is a significant positive correlation between belief and morality. However, I would substitute “belief in God” with “belief in life after death,” as it is not necessary to believe in the anthropomorphic God of religion to accept the strong evidence coming to us from psychical research that consciousness does survive death in a greater reality.

The widespread belief that we have to believe in God and come up with proof of His, Her, or Its existence before accepting the strong evidence for survival, i.e., life after death, is, as I see it, the biggest impediment to understanding the most important concern facing humankind – whether this life is all there is or is part of a much larger life. It is root cause of most of the chaos and turmoil in the world today.

The problem dates back to the fourth century AD when the Council of Nicaea decided to elevate Jesus to the Godhead, in part because Christians needed a humanlike figure to visualize as God and pray to. It was too difficult to visualize a panentheistic God, an abstraction. Many of those who have left religion and adopted a nihilistic worldview have done so because they cannot accept a humanlike figure as God and also cannot visualize a panentheistic God. If they can’t visualize it, they reason, it must not exist. Add in the cruel, capricious nature of the God of religion, and it is not something they want to believe in or give any serious thought to.

Even those who divorce themselves from religion and call themselves agnostics or atheists hold onto the idea that God and an afterlife are concomitants, that consciousness cannot survive death unless there is that “old man in the sky” pulling the strings. The typical militant atheistic diatribe found on the Internet almost always begins by attacking a belief in God while implying that if there is no “big daddy” up there, there can be no afterlife. The atheists ignorantly cling to the premise that there must be scientific proof of God before the evidence for an afterlife can be considered. Meanwhile, those who stick with orthodox religion remain steadfast in their antiquated beliefs and invite the disdain of the non-believers with their evangelizing of ways and means that cannot be reconciled with a just and loving Creator.

If one first considers all the evidence for survival – that coming to us through research in mediumship, near-death experiences, deathbed visions, past-life studies, and Instrumental Transcommunication – and accepts it with some degree of certainty, even if not absolute certainty (call it conviction), he or she doesn’t really need to have a picture of God in mind. It is enough to picture a spirit world where we are reunited with loved ones and live on in a larger life. The picture of that spirit world may be very hazy or out of focus, three-dimensional and mostly inaccurate, but it offers a more tangible and sensible construct than does either the anthropomorphic God or the more abstract, non-personal God. Moreover, it is more meaningful than the limited afterlife provided by orthodox religions, one of angels floating around on clouds while strumming harps and singing praise 24/7 to a narcissistic god. Nor is it necessary to demote Jesus or whomever one sees as representing the Godhead. Many people who believe the same way as Bishop Spong, viewing God in a panentheistic way, see Jesus as something akin to Chairman of the Board in that larger life. Once we accept that so much of it is beyond human comprehension, the difference is one of semantics.

In a way, it is the old chicken and egg paradox, but it really doesn’t require the person to say which came first. It is simply a matter of recognizing that the evidence for life after death is easier to humanly grasp than the evidence for God and that we can visualize an afterlife somewhat better than we can visualize God. The bottom line is that we have to get over the idea that God must be identified and proved before accepting the evidence for the reality of life after death. Until we do that, the moral compass will not reverse itself.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Next blog post: December 4

Read comments or post one of your own

|

To levitate or to be levitated? That is the question.

Posted on 06 November 2017, 11:22

For those who accept the overwhelming evidence that levitations of humans and objects have taken place on numerous occasions, the question is whether the levitations are triggered by some unknown power of the mind, i.e., mind over matter, or whether spirit entities are lifting the person or object.

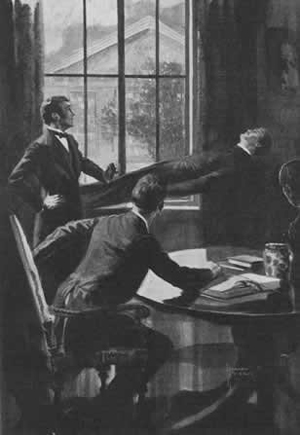

Sir William Crookes, a renowned British scientist who observed a number of levitations with the medium D. D. Home and others, referred to the force giving rise to the levitations as “psychic force” and contended that it can “be traced back to the Soul or Mind of the man as its source.” Crookes did not attempt to identify “soul” or “mind,” but he did say that he and others who had witnessed the psychic force recognized that it may be “sometimes seized and directed by some other Intelligence than the mind of the psychic.” When he reported on witnessing Home, he did not say he saw Home levitate himself. “On three separate occasions I have seen him raised completely from the floor of the room,” is the way he put it. (emphasis mine)

Home, who recalled a feeling of “electrical fullness” about his feet, was usually lifted up perpendicularly with his arms rigid and drawn above his head, as if he were grasping the unseen power raising him from the floor. At times, he would reach the ceiling and then be moved into a reclining position. Some of the levitations lasted four or five minutes.

An artist’s depiction of Home being levitated

Lord Adare, one of Home’s biographers, reported with his father, the Earl of Dunraven, on 78 sittings they had with Home between November 1867 and July 1869 (Experiences in Spiritualism with D. D. Home). Before any phenomenon occurred, Home would go into trance and spirits would often speak through his vocal cords. In the 40th sitting, during December 1868, a spirit began speaking through Home, saying that he would “lift him” on to the table. “Accordingly, in about a minute, Home was lifted up on to the back of my chair,” Adare recorded. “The spirit then told Adare to “take hold of Dan’s feet.” Adare complied, “and away he went up into the air so high that I was obliged to let go his feet; he was carried along the wall, brushing past the pictures, to the opposite side of the room.” After Home was deposited on the floor, the spirit commented that the levitation was badly done and said that “We will lift Dan up again better presently….” However, he was not raised again that night as some other spirit wanted to speak through Home and the spirit who had lifted him gave way to this more advanced spirit.

Of course, the skeptic would say that Home was a trickster or that Adare made it all up or was hallucinating. “Spirit is the last thing I will give in to,” said Sir David Brewster, another famous scientist who witnessed a table levitated in the presence of Home. Michael Faraday, the esteemed physicist, claimed that all such reports about levitations by Home were by incompetent witnesses. Physicist John Tyndall denounced Home and urged him to confess to his fraudulent actions.

Crookes observed Home under lighted conditions and in his own dwelling. Thus, there was no opportunity for Home to rig invisible hoisting wires as skeptics suggested. Moreover, there were many other witnesses to Home’s mediumistic phenomena, including biologist Alfred Russel Wallace, co-originator with Charles Darwin of the natural selection theory of evolution. Wallace witnessed the levitation of a table and a floating hand playing an accordion.

Crookes concluded his report by saying that more experimentation was necessary before it could be determined whether Home and others were somehow defying the laws of gravity by “lifting themselves” or whether they were “being lifted.” Now, nearly a century and a half later, the question remains unanswered and the fundamentalists of science still reject the genuineness of levitation, seeing all past observers of levitations as having been duped, while clinging to the words of Brewster: “They are the observations of ill-trained faculties, the cravings of morbid and mystic temperaments that have been suckled on the husks and garbage of literature, etc.”

While many parapsychologists today accept the genuineness of levitation, the majority of them seem to subscribe to the idea that the levitation is triggered by the medium’s mind. Even though that theory defies known natural law, it is a more “intelligent” and “scientific” one, since it does not require one to profess a belief in “spooks” and other religious folly that science has written off as mere superstition and fraud. Though opposing materialistic beliefs, the subconscious theory does not necessarily lend itself to spiritual ones or to the survival hypothesis.

Nevertheless, it is not all that easy for a person with an open mind to dismiss the records of intelligent and objective men like Crookes, Wallace, Dunraven, Adare, and the dozens of others who witnessed levitations and other psychic phenomenon. Consider the testimony of Dr. Cesare Lombroso, a world-renowned neuropathologist known for his studies in criminal behavior. In his 1909 book, After-Death, What? Lombroso wrote that he had made it an indefatigable pursuit of a lifetime to defend the thesis that every force is a property of matter and the soul an emanation of the brain. For years he laughed at the reports he had heard about levitations and spirits communicating.

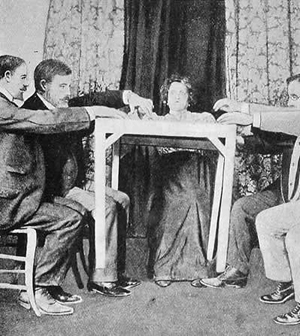

But in the spirit of science, Lombroso sat with Eusapia Palladino on 17 occasions during 1892. He was often joined by other scientists, including Professor Charles Richet, who would later win the Nobel Prize in medicine. On September 28, Lombroso observed Palladino “being levitated” above the table. “The medium, who was seated near one end of the table, was lifted up in her chair bodily, amid groans and lamentations on her part,” he recorded, “and placed (still seated) on the table, then returned to the same position as before.” (emphasis mine)

Palladino table levitation

Lombroso was holding one of Eusapia’s hands, as Richet held the other as she was raised off the floor in her chair while in a state of trance. Eusapia complained of hands grasping her under the arms. Then, her voice changed, and said, “Now I lift my medium up on the table.” (emphasis mine). Lombroso and Richet continued to hold her hands as Eusapia and the chair rose to the top of the table without hitting anything. “After some talk in the trance state the medium (or her spirit control speaking through her) announced her descent, and was deposited on the floor with the same security and precision.” The doctors followed the movements of her hands and body without at all assisting them. Moreover, during the descent “both gentlemen repeatedly felt a hand touch them on the head.” The voice speaking through Palladino’s vocal cords was said to be that of John King, her spirit guide who reportedly took control of her body during her trance states.

At a number of the séances, Lombroso observed a mysterious hand move about and touch the sitters. “Nay, sometimes the fluidic hand has been visible in full light, and seen holding objects, picking the strings of the mandolin, beating the tambourine, lifting things from boxes, putting the metronome in movement with a key,” Lombroso added, noting that the hand was much larger than Eusapia’s and distant from her. (emphasis mine)

By 1903, Lombroso had observed Eusapia many more times, but at a sitting with her in Genoa in 1903, he experienced something new. Under red light, his deceased mother materialized, greeted him, and kissed him. Lombroso wrote that his mother reappeared at least 20 times in subsequent sittings. “I am ashamed and grieved at having opposed with so much tenacity the possibility of psychic facts – the facts exist and I boast of being a slave to facts.” Lombroso concluded. “There can be no doubt that genuine psychical phenomena are produced by intelligences totally independent of the psychic and the parties present at the sittings.” (emphasis mine)

Dr. William J. Crawford, an Irish mechanical engineer, studied the mediumship of 16-year-old Kathleen Goligher over a 2 1/2-year period and claimed to have witnessed “hundreds” of levitations. While initially subscribing to the subconscious theory, Crawford gradually changed his mind and concluded that spirits of the dead were responsible for the levitations and other phenomena. In effect, he saw no reason why the subliminal consciousness of so many mediums around the world would create false identities, such as John King and those of spirit “controls” of other mediums, all intent on masquerading as spirits of the dead while attempting to persuade people that there is life after death. What was to be gained by a deceptive medium, or the trickster personality dwelling in her subconscious, by promoting the spirit world and life after death idea? Why not make herself out to be wizard with telepathic and telekinetic powers independent of any spirit influence? It simply didn’t make sense that mediums around the world who didn’t know each – at a time when communication was very slow and difficult – would all collaborate in such a deception.

Crawford may have been influenced by Wallace’s comments. “On the second-self theory, we have to suppose that this recondite but worser half of ourselves, while possessing some knowledge we have not, does not know that it is part of us, or, if it knows, is a persistent liar, for in most cases it adopts a distinct name, and persists in speaking of us, its better half, in the third person” Wallace had earlier opined.

Lending itself to the subconscious theory is the research done by some Canadians during the 1970s in which they supposedly created a spirit to whom they gave the name Philip. This imaginary ghost was able to levitate a table. This and similar studies have strengthened the idea that it’s all in the mind. But Allen Kardec, a pioneer in psychical research, addressed the imaginary spirit situation a hundred years earlier in his 1874 book, The Book of Mediums. “Frivolous communications emanate from light, mocking, mischievous spirits, more roguish than wicked, and attach no importance to what they say,” he offered. “These light spirits multiply around us and seize every occasion to mingle in the communication; truth is the least of their care; this is why they take a roguish pleasure in mystifying those who are weak, and who sometimes presume to believe their word. Persons who take pleasure in such communications naturally give access to light and deceiving spirits.”

Kardec added: “Just the same if you invoke a myth, or an allegorical personage, it will answer; that is, it will be answered for, and the spirit who would present himself would take its character and appearance. One day, a person took a fancy to invoke Tartufe, and Tartufe came immediately; still more, he talked of Orgon, of Elmire, of Damis, and of Valire, of whom he gave news; as to himself, he counterfeited the hypocrite with as much art as if Tartufe had been a real personage. Afterward, he said he was the spirit of an actor who had played that character.

Who is to say that such a mischievous spirit was not playing along with the Canadian group? There is also the possibility that the doubles, or spirit bodies, of the Canadians were doing the lifting, which gives a different twist to the subconscious theory. That is, the “mind” is really spirit. It is all very mystifying and it appears unlikely that science will ever have a satisfactory answer to the question of levitating vs. being levitated.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Next blog post: November 20

Read comments or post one of your own

|