|

|

|

|

Overcoming Existential Angst with Afterlife Evidence

Posted on 28 March 2022, 8:58

According to several internet references, old-age begins at 65, but 65-74 is “young-old,” while 75-84 is “old” and 85-and-up is “old-old.” As I cross the threshold into that oldest classification, perhaps best referred to as “dotage,” it seems like an appropriate time to philosophize, including looking back at how my views on God and the afterlife have changed with the four seasons of life, as depicted in the accompanying collage – youth, young adulthood, middle-age, and old age.

My earliest beliefs were molded by the Catholic Church. There was no question about the existence of God or an afterlife, one that had three possibilities – heaven, purgatory, and hell. All those going to purgatory would eventually make it to heaven, although it might take a few hundred years of pain and suffering equivalent to that in hell before one had purified himself enough for graduation to heaven. The afterlife seemed like a pretty dull place, but it was too far in the future to concern myself with the lack of entertainment and excitement there. I was a curious kid (top left photo) and often struggled with the Catholic teaching that one could live a sinful and shameful life but still make it to heaven, via purgatory, by confessing his sins on his deathbed, while another person could live a relatively virtuous life and be condemned to hell for eternity if he died with a single sin on his soul, one that he had not yet confessed. It just didn’t seem fair and I couldn’t imagine that a just God would permit a system that was based for the most part on luck.

My high school biology teacher professed a belief in Darwin’s theory of evolution, although he was very careful in setting it forth as dogma. At that time, the early 1950s, I, and many others, took a belief in Darwinism to be one of atheism, and I couldn’t understand how such a nice and intelligent guy could have such a “demonic” belief. As a college freshman, I took a philosophy course in which I was fully awakened to the idea that there might not be a God or an afterlife. But death was too far off to let nihilism really bother me too much. I clung to my Catholic beliefs but with more skepticism than before.

During my three years of obligatory military service following college, I concluded that military life, while offering much travel and an abundance of adventure and learning experiences, was not for me. However, not long before the completion of my tour of duty, I participated in a military track meet and excelled to the point that the commanding general invited me to his office to congratulate me. The general noted from my file that I would soon complete my service and asked if I had given any consideration to making the military a career. My athletic victories apparently outweighed my lack of a “gung-ho” attitude, as must have been evident in my file on the general’s desk. I didn’t go into detail with the general, but my primary reason for not being interested in such a career was an existential one, probably my first real existential reasoning.

We were between the Korean War and the Vietnam War at the time and I reasoned that if I were to succeed in a career as a military officer I would have to hope for a war in order to have fulfillment in my career. The alternative was to complete a 20-year military career without ever having put all my training into practice. I saw it as a no-win situation – either continually hope for a war and have one or have a career in which all my efforts went for nothing beyond being prepared for something. I discussed the dilemma with several fellow officers and was surprised to find out that they had never considered that aspect of it. Moreover, they didn’t seem to fully grasp my mental conflict or to be interested in giving it any thought. I was puzzled and wondered if I had been digging too deeply into the future.

No Carpe Diem

At that time, I was just beginning to struggle with the much greater existential concern of whether life had any meaning. Even if I were to find some fulfillment in a career, I wondered to what end. I never was a “carpe diem” person. I could find no enjoyment in eating, drinking, and being merry in the time not allotted to preparing for war or later in working a nine-to-five job in the civilian life. I definitely wasn’t the “party animal” that many of my friends were. I could make absolutely no sense of smoking, a popular endeavor at the time, and I found beer and all other alcoholic beverages very distasteful. The materialistic, hedonistic, or Epicurean lifestyle that most of my friends sought had no appeal, even though I made several attempts at experiencing it (top right photo). Fortunately, my “existential angst” during those early years was soon mitigated significantly by the demands of family life, a career, sport (bottom left photo), and other escapes from reality – a reality in which seemingly few pause to ask the meaning of it all.

In his 1974 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Denial of Death, anthropologist Ernest Becker explains that we all use repression to overcome death anxiety. That is, we bury the idea of death deep in the subconscious. Borrowing from Blaise Pascal, the seventeenth-century French philosopher, Becker points out that we literally drive ourselves into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, and personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of the situation that they are a form of madness – “agreed madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.”

My madness continued through most of my forties. An empty nest at home, reaching a plateau of achievement and advancement at work, and a significant decline in athletic performance due to the effects of aging all prompted me, at around age 50, to come to grips with my madness and give more thought to existential matters. I soon realized that I was a victim of what Soren Kierkegaard, known as “the father of existentialism,” referred to as philistinism – tranquilizing oneself with the trivial. As Kierkegaard saw it, most people in despair from philistinism don’t even realize they are in despair.

I considered the humanist approach that life is all about making it a better world for future generations, but I ran into a roadblock when I tried to put myself in the place of a descendant several generations ahead with all the leisure and comforts of a true Epicurean, and wondered what I would then do to make it even more pleasurable. Wouldn’t it just lead to more materialism, more hedonism, then monotony or insanity?

Now, at the mid-point of my ninth decade of life (lower right art, thanks to Michael Hughes), I often reflect on the various crossroads in life, wondering where I would be at this moment if I had chosen a different path, or even if I would still exist as a human being.

Then What?

All that came to mind recently while reading Return of the God Hypothesis by Stephen C. Meyer, the director of the Center for Science and Culture at Discovery Institute in Seattle. Meyer writes that the problem of human significance began to torment him when he was 14 years old and an ardent baseball fan. He thought about a player achieving great success on the ballfield, being elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame, thereby achieving “immortality of sorts,” but then he would die. “Then what? What did any of those numbers measuring his achievements mean after that?” Meyer asked himself. He further recalled wondering about the “lasting meaning” of a great surgeon who had saved many lives during her career – lives which had all now expired.

Meyer began to see his concerns as “a metaphysical panic, a fear of the meaninglessness of life.” He could find no lasting value or meaning in any human achievement, nor in love or kindness. In later years, he “encountered many other people, particularly students, who have experienced a similar metaphysical anxiety about whether their lives or human existence generally has any ultimate purpose.” He suspects that such hopelessness has contributed to the epidemic levels of suicide among young people and that the plague of opioid addiction around the world is an attempt by people to numb themselves against a gnawing despair that has to do with what they see as a meaningless life. To that I might add a recent report that alcohol-linked deaths surged in the pandemic’s first year, rising from 78,927 in 2019 to 99,917 in 2020. What might the numbers be of the alcoholics who didn’t die?

Meyer has been able to overcome his angst by studying all the evidence suggesting Intelligent Design of our universe. If I am interpreting him correctly, he infers from such design that there is a God and deductively draws from that premise that consciousness must continue after death. I don’t quite understand how Meyer moves from the reality of God to the reality of a larger life after death, but if that works for him and others, good for them.

For me, it has been inductive reasoning from some 35 years of studying psychical research and related stories that has provided a conviction that consciousness does survive death in a larger life. That conviction leads me to believe that there is an Intelligence behind it all, but I don’t see the need for searching for, identifying, and examining the Intelligence before considering the survival aspect. Moreover, the years of study have led me to believe the afterlife is much more than the humdrum heaven I envisioned during my youth and that the negative afterlife is not an eternal one. I accept that it is beyond human comprehension, at least mine, but that, however it plays out, it is something that will not disappoint those who have lived essentially moral, productive and positive lives of love and service.

The bottom line here is that as I advance from old age into the dotage stage of life, I am most thankful for the guidance provided, possibly from invisible sources, in understanding and overcoming much of the madness I once experienced. I realize that a certain amount of madness is necessary to cope and survive in our complex world. As Pascal said, “not to be mad would amount to another form of madness.” However, tempering the madness and integrating it with a more infinite and cosmic consciousness is, I believe, the key to avoiding extremes of madness during one’s declining years. As the great German thinker Goethe put, we must plunge into experience and then reflect on the meaning of it. All reflection and no plunging drives us mad, but all plunging and no reflection makes us brutes.

Moreover, I have no regrets about choosing the paths I took at those critical crossroads, even though, in retrospect, some of them were likely much more challenging and demanding, even more painful, than the ones I turned away from. Would a life without adversity have any meaning? Onward Christian Soldiers!

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next Blog Post: April 11

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

Mediumship: Psychic Rods, Alleged Trickery and Psychic Stuff

Posted on 14 March 2022, 9:23

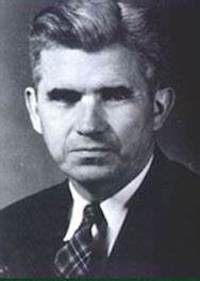

Perhaps the most damning evidence against the mediumship of Mina Crandon, also known as “Margery,” came from Dr. Joseph B. Rhine (below), then a young botanist turned psychologist and later one of the founders of the field called parapsychology. “We were disgusted to find that at the bottom of all this controversy and investigation lay such a simple system of trickery as we witnessed at the séance,” Rhine reported of his one sitting with Margery on July 1, 1926. “We are amateurs, and we do not possess any skill or training in trickery, and we were looking for true psychic productions, but in spite of our greenness and our deep interest, we could not help but see the falseness of it all.” One thing that stood out in Rhine’s report is movement of her feet at the time psychokinetic action was taking place.

Several other investigators, including the famous magician Houdini, agreed with Rhine. He was sitting next to her, holding an arm and a leg, to rule out fraud. He said that he felt movement in her leg when a bell rang some distance from them. Others were convinced that Margery was a genuine medium and still others sat on the fence and weren’t sure what to believe. Those with the most experience in such research and with the most experiments with Margery found in her favor. Compared with Rhine’s one sitting with Margery, Dr. Mark Richardson, a distinguished Harvard professor of medicine, had more than a hundred sittings with her, including a number of individual experiments, and was certain that there was no fraud involved.

“There comes a point at which this hypothesis of universal confederacy must stop; or if not this, that the entire present report may be dismissed off-hand as a deliberate fabrication in the interests of false mediumship,” Richardson wrote. “I respectfully submit that no critic who hesitates at this logical climax may by any means escape the hypothesis of validity. If the present paper is worthy of and if it receives the slightest degree of respectful attention, the facts which it chronicles must constitute proof of the existence of Margery’s supernormal faculties, and the strongest sort of evidence that these work through the agency of her deceased brother Walter.”

Present with Dr. Rhine in that one sitting with Margery was Dr. Louisa W. Rhine, his wife. It was noted that Louisa Rhine did not recognize the “tricks,” but that she accepted her husband’s explanation of them. Ironically, Louisa Rhine served as a translator for a two-part article by Professor Dr. Karl Gruber of Munich, Germany appearing in the May and June 1926 issues (two months before their sittings) of The Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research dealing with the problems of understanding such mediumship. No mention was made of Margery in the article, but the concerns were the same.

Gruber was a German physician, biologist, and zoologist who had conducted or participated in numerous studies of other physical mediums, including German mediums Willi and Rudi Schneider. He observed “synchronous movements” between the medium and objects out of the medium’s reach. “If this connection is broken by movements of the hand or other object across the field of activity, or if it is roughly torn away, either temporary or lasting bodily injury to the medium results,” Gruber explained, noting that his research involved more than one-hundred experiments. “This fact has been repeatedly misunderstood by the skeptical, who have seen in it the unmasking of a frightened medium.”

Gruber cited the reports of Dr. William J Crawford, an Irish mechanical engineer. Between 1914 and 1917, Crawford carried out 87 experiments with Irish medium Kathleen Goligher and concluded that the movement of some table or other object out of Goligher’s reach resulted from invisible “psychic rods” extending from the medium to the object being moved. These psychic rods were made of what others called “ectoplasm” or “teleplasm,” though Crawford referred to it as “psychic stuff.” They originated with what Crawford called “operators,” which he took to be discarnate human beings. “These particular mechanical reactions cause her to make slight involuntary motions with her feet, motions which a careless observer would set down as imposture,” Crawford explained. “The starting point of the rod then seems to be much higher up her body, for the reactionary movements are then visible on the trunk.”

Absent from all the observations and opinions of the esteemed scientists and other ‘experts’ studying Margery is evidence that might have given the doubters and deniers second thoughts before claiming fraud. That is, the researchers expressed their opinions strictly from a mechanistic/materialistic point of view. There is no mention of the research twenty to thirty years earlier with Eusapia Palladino, an illiterate Neapolitan medium who was studied by many leading scientists. Some of the those studying Palladino suggested that her “third arm,” an ectoplasmic extension molded by her spirit control, known as “John King,” was carrying out the activity which they saw as fraud. Moreover, some of the investigators reported on “rhythmic actions” of her fingers, arms and legs that were in accord with activity taking place some distance from her, apparently through the invisible or mostly invisible ectoplasmic rods extending from her limbs to the point of activity, as if she, or the spirit controlling her, had become puppet masters of sorts. “When [Professor Oscar] Scarpa held Palladino’s feet in his hands (for control purposes), he always felt her legs moving in synchrony with ongoing displacements of the table or chair,” reported Professor Filippo Bottazi, who referred to the action as “synchrony.”

The fundamental problem in all such analyses, as I see it, is that the spirit hypothesis is completely disregarded, as it is “unscientific.” Bottazi, who rejected the spirit hypothesis, mentioned that they would refer to John King to appease Palladino, who was certain he was a spirit guide, but they apparently laughed at the whole idea when they were not in her presence. “Spirits, ha, ha, preposterous humbug,” they likely reacted while clinging to the idea that it all originated in Palladino’s subconscious in ways that science did not yet understand.

Sir Oliver Lodge, a distinguished British physicist, also suspected fraud with Palladino. When he accused her of a trick, she went into a rage and explained that when she was in a trance John King was in control. “She wanted us to understand that it was not conscious deception, but that her control took whatever means available, and, if he found an easy way of doing a thing, thus would it be done,” Lodge reported. “I am willing to give her the benefit of the doubt, so far as the morals of deception are concerned, for she was a kindly soul, with many of the instincts of a peasant, and extraordinarily charitable.”

Present with Lodge in those experiments with Palladino was Dr. Charles Richet, later a Nobel-Prize winner in medicine. He stated that he had nearly 200 séances with Palladino and was certain that she was not a cheat. However, he was reluctant to accept John King as the spirit of a dead person, as that would be a very unscientific approach, but he concluded that the semi-unconsciousness of the medium takes away much of her moral responsibility. “Trance turns them into automata that have but a very slight control over their muscular movements,” he explained. “… It is also quite easy to understand that when exhausted by a long and fruitless séance, and surrounded by a number of sitters eager to see something, a medium whose consciousness is still partly in abeyance may give the push that [she] hopes will start the phenomena.”

Lodge reported on a test involving a spring dynamometer, which, when squeezed, measured hand grip strength. It was Richet’s idea that all the energy used at a sitting had to come from the medium or some of the sitters. Thus, he recorded the grip strength of Eusapia and each sitter before and after the two-hour sitting. In the before reading, Lodge, a big man at 6-foot-4, scored the highest, followed by Richet, Frederic Myers, and Julian Ochorowicz, with Eusapia’s being much weaker than the four men. But after the sitting, Eusapia was giving a feeble clutch when she suddenly shouted, “Oh, John, you’re hurting!” and the men observed the needle go far beyond what any of them could exert. “She wrung her fingers afterwards, and said John (King) had put his great hand around hers, and squeezed the machine up to an abnormal figure,” Lodge explained, noting that “John King” occasionally showed his hand, “a big, five-fingered, ill-formed thing it looked in the dusk.”

As with John King, most of the researchers spoke with Margery’s “Walter” personality, which claimed to be Margery’s deceased brother, as if he was a real spirit, even though they refused to accept the idea of spirits. As they saw it, the “third arm” extending from Margery could not have been that of a spirit entity, because science says that spirit entities don’t exist. It had to be a trick by Margery, even though it went beyond any scientific laws then known. One of the exceptions was Dr. T. Glen Hamilton, a Canadian physician and psychical researcher .

“… I was privileged to take part in a tête-à-tête with Dr. Richardson’s justly famous voice cut-out machine, and found it to be absolutely fraud-proof and 100 percent effective in proving the independence of the “Walter” voice,” Hamilton wrote. “I witnessed as well a number of other successful tests with this machine. At one of these sittings, I witnessed also one of the most arresting incidents in my research experiences: a trance so profound that the medium’s respirations were reduced to six to the minute…Undoubtedly this affords a very strong additional proof of the genuineness of the Margery mediumship.”

At Hamilton’s first sitting in Winnipeg, Margery disrobed in front of Mrs. Hamilton and put on a bathrobe that was supplied for her. It took between three and four minutes for Margery to go into a trance, after which Walter spoke in what was described as a “hoarse stage-whisper.” He joked, teased, and even preached as Hamilton closely observed Margery, being controlled by two other physicians, to rule out fraud. “I have now witnessed the Margery phenomena eleven times: eight times in the Lime Street séance room under conditions of careful control; twice in my own experimental room, also under positive control; and once in the home of an acquaintance under arrangements entirely impromptu – and in each instance typical Margery phenomena occurred…I have no hesitancy in again stating that I am quite convinced that the Margery phenomena are not only genuine but are also among the most brilliant yet recorded in the history of metapsychic science.”

Hamilton concluded that the “trance-intelligences” of the mediums he had studied, existed apart from the mediums. “Assuming the reality of other-world energy-forms, how then do they come to be fleetingly represented (or mirrored) in our world?” he asked. He concluded that teleplasm (or ectoplasm) provides the answer. “Basing my assumption on a study of the sixty-odd masses which we have photographed during the past five years (1928-1934), I regard teleplasm as a highly sensitive substance, responsive to other-world energies and at the same time visible to us in the physical world. It therefore constitutes an intervening substance by means of which transcendental intelligences are enabled, by ideoplastic or other unknown processes to transmit their conception of certain energy forms which appear objective to them, into the terms of our world and our understanding.”

And, yet, most scientists and historians still cling to the fraud hypothesis. My guess is that the spirit world gave up in trying to prove themselves.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next blog post: March 28

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

|

|