|

|

|

|

Conversations with the Dead: Real or Imagination?

Posted on 31 July 2023, 19:18

Of the 350 or so blogs I have written over the past 14 years, only two or three have involved Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP), or as it is more broadly categorized today Instrumental Trans Communication (ITC). I wasn’t especially impressed with the communication as nearly all I had come across offered little more than a few words or some fragmentary sentences that I likened to finding faces or figures in the clouds. The exceptions have been several books by Anabela Cardoso which have offered more complete and understandable messages. (See my interview with Dr. Cardoso in the archives for December 4, 2017)

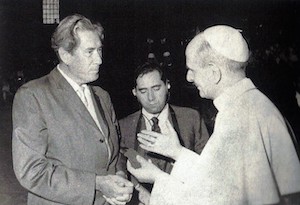

My latest read in this field is Friedel’s Conversations with the Dead, co-authored by Cardoso and Anders Leopold and recently published by White Crow Books. As the sub-title states, it is “the fascinating story of Friedrich Jűrgenson, (below) pioneer of EVP.” The original book was authored by Leopold and published in Sweden in 2014. Cardoso has translated and edited it into English.

Leopold was a friend of Jűrgenson’s. “We remained close friends until October 15, 1987, when he went over to the other side, to what he called ‘life in the fourth dimension’,” Leopold writes in the introduction, describing Jűrgenson as a man of immense charisma and joy of life and the discoverer of EVP – electronically mediated contacts with another dimension of life via tape recorder and radio. He goes on to explain that ITC go beyond EVP by including contacts via computers, TV and telephone.

“A man of great culture and artistic value, an atheist cherished by two popes, Friedel, as he was affectionally known, unwittingly discovered the electronic voices of the dead in a remote forest in Sweden…,” Cardoso states in the preface of the book. Jűrgenson, who was born in Odessa, Russia in 1903, gained a reputation as an opera singer. artist, and film producer. He is said to have spoken eight languages, five fluently. He was commissioned by the Vatican to do art work and filming in Pompeii and portraits of two popes.

Jűrgenson’s interest in EVP began in 1959 while attempting to record birdsongs in the forest. Instead of birdsong, he recorded voices, one of them being that of his deceased mother. He then began experimenting and recording other voices, but he didn’t go public with it until calling a press conference on June 15, 1963. The book includes the reports of several of the journalists attending that press conference. The tapes were not played for the journalists; they reported only what Jűrgenson told them. Quoting parts of their reports might best summarize the phenomenon as Jűrgenson explained it to them.

Anne-Marie Ehrenkrona, said to be one of Sweden’s most famous writers, wrote an objective report based on what Jűrgenson reported, including:

“The [tapes] have nothing whatsoever to do with the occult.”

“The voices intervene in the regular programs – in opera arias, popular songs, speeches of messages – by changing the text, simply flushing over the real program.”

“To break away from the ordinary speech more easily, the voices use a mixed language and ungrammatical forms – German articles, for example, do not matter.”

“The contact is made possible by the radio waves, which they, the communicators, thanks to a higher frequency, amplify or throw away. Or more transcendently put: the radio waves pave the way for vibrations from a higher plane.”

“Jűrgenson’s ‘space’ theory is that the voices want to make our lives more pleasant by eliminating the fear of death, our great anxiety, and to teach us to live harmoniously in the present.”

Ivan Bratt, a Swedish newspaper reporter, was more skeptical and a little cynical in his report but still respectful of Jűrgenson. He wrote, in part:

“Jűrgenson reported with passionate insight about his contacts with friends from the other side of the grave. His eagerness to convince his audience could not be mistaken, nor his absolute conviction that he is right.”

“The language the dead use in their messages is a kind of polyglot speech in which most European languages are represented.”

“The dead have ‘radar’ and can use it to see us walking around on the Earth. They can also see and hear what we think and feel. With this radar, they send their messages carried through radio waves to Jűrgenson’s radio…”

“No sorrow and no pain, no worries but only joy and mirth, this is life in the fourth dimension.” (seemingly cynically stated)

“Thus, the information provided at the famous press conference was rather hard to digest and as previously mentioned, it was received with obvious skepticism. The impression remains that there must be something there, but the big question is what is it? Maybe we will eventually get the answer, maybe not.”

Rune Moberg, said to be one of the most distinguished members of the Swedish media, reported:

“The dead, explained Jűrgenson, have not the same kind of consciousness as we do, and not the same conceptual realm. What we think is pointless can have a deep meaning for them.”

“God help me. I began to believe. And it felt good. Imagine that you do not die when you die. And the spirits seem to be well wherever they are staying. They sing and joke.”

“I do not know what to believe. However, I know what I should not believe. I do not think Friedrich Jűrgenson is a deliberate hoax.”

Jűrgenson’s research was not without considerable scientific observation and validation. Professor Hans Bender, a German psychologist of the University of Freiburg, Dr. Friedbert Karger of the Max Planck Institute in Munich, Dr. John Bjoerkhem, a pioneer in Swedish parapsychology, and other scientists and scholars studied his work.

A second press conference took place on June 12, 1964, shortly after the release of Jűrgenson’s book, The Voices from Space. Tapes were played for the 40 or so journalists and photographers in attendance. “During the evening they listened to various recordings and became immediately convinced that Friedel had undoubtedly discovered a revolutionary opportunity for communicating with, as Claude (Thorlin, another EVP experimenter) put it, an ‘extraterrestrial’ living area,” Leopold wrote, further commenting that Jűrgenson accomplished what he had hoped for: interest, curiosity, commitment and utter shock.”

Leopold further noted that Jűrgenson received ‘huge” publicity, although many of the journalists reported it with a certain skepticism. “But at the same time, they could not hide from the inexplicable experience at Friedel’s house along with a group of colleagues and witnesses who claimed to hear voices from close relatives, dead for several years.”

It is difficult for the reader to fully appreciate the communication as Leopold continually mentions or quotes the indistinct, soft, garbled and fragmentary nature of the voices, often left to the interpretation of the listener. Nearly all the messages come across as gobbledygook, few of them making any sense, although Jűrgenson seems to have been able to interpret many of them, due in part to his ability to speak many languages and to his finely tuned musical ears in addition to what seems to have been clairvoyant abilities. Leopold states that there are about two-thousand recordings in Jűrgenson’s collection, about a third of the total “characterized by clear text and unmistakable communications that can be understood without any doubt by all who possess normal hearing.” Nevertheless, the examples provided in the book will not likely help the non-believer move from a skeptical perch or even the deeply religious person give up his or her idea of heaven and hell. One of the communicators was said to be Hitler and the only thing he had to say that made sense to me was that “we lived in the deepest confusion.”

A very interesting chapter has to do with Jűrgenson’s art work and film-making in Pompeii and his talks with Pope Paul VI about the EVP voices and other matters. In his conversations with Jurgenson, the pope is quoted: “We are following your research with great interest. We have also our own research on this topic. This is not contrary to the Church. We know that between death and resurrection there is another sphere of existence, a post-Earthly existence…We have an open mind on all issues that are not contrary to the teachings of Christ.”

Although he had no doubt about the honesty and integrity of Jűrgenson, author Leopold struggled to reconcile the gibberish he could hear with the profound interpretations by Jűrgenson. Before writing the book in 2014, he began his own experimentations with EVP. “On Friday, September 7, 2012, I received a greeting from my wife Mona who passed away on July 15, 2010,” he explains. “I identified the voice immediately but took several safety precautions straightaway to avoid the worst trap: self-suggestion and wishful thinking. For me, there is no doubt that the voice belongs to Mona. It is unbelievable and it hit me very hard when I heard her.”

Leopold quotes Dr. Nils-Olof Jacobson (1937-2017), a psychiatrist who wrote extensively on the subject matter: “We can speculate about many explanations. In some cases, we can imagine psychokinesis, as how we unconsciously produce this phenomenon. But that is no explanation, rather only a label we put on something we do not understand. Perhaps we, by an unknown form of psychokinesis, can create a kind of ‘phantoms,’ which then live their own lives. Some of these stories are in the esoteric literature. Everyone must decide whether these explanations seem reasonable and adequate. Maybe ‘aliens’ are involved. Maybe there are parallel worlds. Maybe there is life after death. Maybe everything is connected in the universe, beyond space and time limits. We easily believe that the part of the reality we see is the only reality.” According to Cardoso, Jacobson supported the life after death explanation over the others.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next blog post: August 14

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

Long before the White Crow, there was Catherine Crowe

Posted on 17 July 2023, 7:44

The so-called “Rochester Knockings,” referring to the “rappings” phenomenon experienced by the Fox sisters in the hamlet of Hydesville, just outside Rochester, New York, on March 31, 1848, is often cited as the advent of what came to be called Spiritualism, a belief based on communication with spirits of the dead. One might get the impression that before the Fox sisters there was no evidence of any kind that we live on in a larger world. However, that is clearly not the case.

That very year, 1848, The Night Side of Nature: Or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers by Catherine Crowe, (below) a renowned English author, was published by George Routledge and Sons of London and New York. All indications are that the book was authored before Crowe had heard of the Fox sisters. There is no mention of them in the book and most of the phenomena mentioned in the book clearly took place before 1848. Crowe discussed apparitions, doppelgangers, deathbed phenomena, dreams, clairvoyance, and other psychic phenomena suggesting a spirit world.

One reference gives Crowe’s years on the earth plane as 1803 to 1876, another as 1790 to 1872. She is referred to as an English novelist, playwright, writer of social and supernatural stories, and “the original ghosthunter.” She is also remembered for translating and publishing, in 1845, the first English version of Dr. Justinus Kerner’s 1829 book, The Seeress of Prevorst, the name given to Frederika Hauffe (1801-1829), a German mystic and clairvoyant.

‘They are afraid of the bugbear, Superstition….”

“We are all educated in the belief of a future state, but how vague and ineffective this belief is with the majority of persons, we too well know,” Crowe stated in the introduction of her 1848 book, “for although the number of those who are called believers in ghosts, and similar phenomena, is very large, it is a belief that they allow to sit very lightly on their minds. They feel that evidence from within and from without is too strong to be altogether set aside, but they have never permitted themselves to weigh the significance of the facts. They are afraid of that bugbear, Superstition – a title of opprobrium which it is convenient to attach to whatever we do not believe ourselves.”

Discounting stories of the ferryman and the three-headed dog, Crowe concluded that some stories relating to “what awaits us when we have shaken off the mortal coil,” may have some foundation in truth. She pointed out that in the seventeenth century credulity outran reason and discretion, but the eighteenth century “flung itself into an opposite extreme.” She speculated that interest in the subject at the time of her writing the book was at its lowest point ever. “The great proportion of us live for this world alone, and think very little of the next; we are in too great a hurry of pleasure or business to bestow any time on a subject which we have such vague notions – notions so vague, that, in short, we can scarcely by any effort of the imagination bring the idea home to ourselves; and when we are about to die we are seldom in a situation to do more than resign ourselves to what is inevitable, blindly meet our fate; whilst, on the other hand, what is generally called the religious world, is so engrossed by its struggles for power and money, or by its sectarian disputes and enmities; and so narrowed and circumscribed by dogmatic orthodoxies, that it has neither inclination nor liberty to turn back or look around, and endeavour to gather up from past records and present observations, such hints as are now and again dropped in our path to give us an intimation of what the truth may be.”

As she saw it, another change in worldview was approaching, as it apparently did with the Fox sisters. “The contemptuous scepticism of the last age is yielding to a more humble spirit of inquiry; and there is a large class of persons amongst the most enlightened of the present, who are beginning to believe that much which they had been taught to reject as fable, has been, in reality, ill-understood truth.”

Andrew Jackson Davis, known as the “Poughkeepsie Seer,” is not mentioned by Crowe, probably because he lived in far-away America and did not begin to make a name for himself as a clairvoyant until 1846, when he was just 20 years old. In his 1847 book, Principles of Nature, Davis recorded, allegedly by means of automatic writing from the spirit world: “It is a truth that spirits commune with one another while one is in the body and the other in the higher spheres – and this, too, when the person in the body is unconscious of the influx, and hence cannot be convinced of the fact; and this truth will ere long present itself in the form of a living demonstration. Then, in his diary, on March 31, 1848, he recorded: “About daylight this morning a warm breathing passed over my face and I heard a voice, tender and strong, saying, ‘Brother, the good work has begun – behold, a living demonstration is born.’ I was left wondering what could be meant by such a message.” As stated, on that very same day, the Fox sisters had their first experience with the rappings.

Crowe’s book preceded Darwinism by a dozen years, but it is now clear that the tide did change somewhat with Spiritualism and more so with the formation of the Society for Psychical Research in 1882, before again receding during the hedonism of the “Roaring 20s,” advancing again during the 1970s with NDEs, past-life studies, and other research, then again receding over the past 20 years. We seem to be at a very low tide at this time.

“It makes me sorrowful when I hear men laughing, scorning, and denying this their birthright….”

Crowe recognized that the phenomena she discussed in her book had no scientific or philosophical value. “We must confine ourselves wholly within the region of opinion,” she wrote, stating that to go beyond opinion “we shall assuredly founder.” She further recognized that many enlightened people would scoff and sneer at the phenomena. “I confess it makes me sorrowful when I hear men laughing, scorning, and denying this their birthright; and I cannot but grieve to think how closely and heavily their clay must be wrapt around them, and how the external and sensuous life must have prevailed over the internal, when no gleam from within breaks through to show them these things are true.”

Generally, many of the phenomena of Crowe’s era were referred to as “spectral illusions,” but it was becoming increasingly clear that some went beyond illusion. “It is true that some of the phenomena resulting from [human] faculties are simulated by disease, as in the case of spectral illusions,” she wrote, “and it is true that imposture and folly intrude their unhallowed footsteps into this domain of science, as into that of all others, but there is a deep and holy well of truth to be discovered in this neglected by-path of nature, by those who seek it, from which they may draw the purest consolations for the present, the most ennobling hopes for the future, and the most valuable aid in penetrating through the letter into the spirit of Scriptures.”

Crowe claimed that Germany was well ahead of England and the rest of the Western world in its search for the soul of man. In addition to the research carried out by Kerner with Hauffe and others with psychic abilities, Crowe cited that of Dr. Karl von Reichenbach, a German chemist remembered for his study of what he called the Odic Force, apparently an earlier name for ectoplasm, and Dr. Johann Heinrich Jung-Stilling, who also studied psychic matters. “It is a distinctive characteristic of that country, that, in the first place, they do think independently and courageously,” she wrote.

“[A]nd, in the second place, that they never shrink from promulgating the opinions they have been led to form, however new, strange, heterodox, or even absurd, they may appear to others. They do not succumb, as people do in this country, to the fear of ridicule, nor are they in danger of the odium that here pursues those who deviate from established notions; and the consequence is that, though many fallacious theories and untenable propositions may be advanced, a great deal of new truths is struck out from the collision, and in the result, as must always be the case, what is true lives and is established, and what is false dies and is forgotten.

“But here in Britain our critics and colleges are in such haste to strangle and put down every new discovery that does not emanate from themselves, or which is not a fulfilling of the ideas of the day, but which, being somewhat opposed to them, promises to be troublesome from requiring new thought to render it intelligible, that one might be induced to suppose them divested of all confidence in this inviolable law; whilst the more important, and the higher the results involved may be, the more angry they are with those who advocate them. They do not quarrel with a new metal or a new plant, and even a new comet or a new island stands a fair chance of being well received; the introduction of a new planet appears, from late events, to be more difficult, whilst phrenology and mesmerism testify that any discovery tending to throw light on what most deeply concerns us, namely our own being, must be prepared to encounter a storm of angry persecution.

“And one of the evils of this hasty and precipitate opposition is that the passions and interests of the opposers become involved in the dispute; instead of investigators, they become partisans; having declared against it in the outset, it is important to their petty interests that the thing shall not be true, and they determine it shall not, if they can help it.”

Some 175 years have passed since Crowe wrote those words and little seems to have changed in our search for the soul.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next blog post: July 31

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

Professor discusses “The new Catholicism” in his latest novel “The Womanpriest”

Posted on 02 July 2023, 10:45

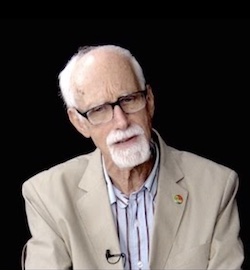

In his latest book, a novel titled The Womanpriest, Dr. Stafford Betty, (below) a retired professor of religious studies, deals with many issues facing society, religion, and the Catholic Church, now and in the future. The protagonist is an indomitable woman priest whose life revolutionizes the Catholic Church. In addition to the issue of a woman serving in the priesthood and in higher offices within the Church, Betty discusses a number of other controversial subjects, including the nature of God, the nature of the afterlife, the atonement doctrine, abortion, homosexuality, the infallibility of the pope, suicide, and a “heap of outdated doctrine and arrogant old men.”

Most of the readers of this blog are likely familiar with Professor Betty. He is the author of Heaven and Hell Unveiled and When Did You Ever Become Less by Dying?, both published by White Crow Books. My prior interviews with him can be found in the archives for May 30, 2011, June 30, 2014, and January 14, 2019. With the issues discussed in his current book, I concluded it was time to again put some more questions to him.

Stafford, almost all your recent writing, including three nonfiction books and two novels, has been focused on the afterlife. But your latest novel, The Womanpriest, is about Catholicism. Why the change?

Well, as a former Catholic raised since boyhood in the faith, I’ve retained an interest in it and a certain nostalgia for it. But I am also critical of it, so much so that I’ve gravitated away from it toward its far more rational and progressive cousin, Anglicanism, or what we call in America the Episcopal Church. The Womanpriest is not about the Catholic Church as it exists today but a future Church that doesn’t exist but should. I wrote the novel as a blueprint for this future church, culminating in the election of a woman to the papacy in 2080. Besides an entertaining story, as every novel must be, it shows how this extraordinary woman, Macrina McGrath, with plenty of help along the way, transforms the Church into something worthy of the name Catholic. I’m a teacher from first to last and am always looking to make things better. Thus this novel.

Can you say a little more about what led you to leave the Church?

It began when I was 25 and just back from Vietnam. My faith had served me well during the war: I was so certain of heaven that I lived without the fear that most of the other officers had. As the public information officer, I helicoptered to hot spots to get stories from the front lines and lived in what William James called “the strenuous mood.” It all came apart when I read Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian when I got back stateside. What happened? I realized I had no evidence for God’s existence, Christ’s divinity, and, most importantly, an afterlife. Even worse, Russell made the doctrines I treasured seem ridiculous. I came away a troubled, unhappy agnostic and enrolled in a theology program at Fordham University to see if the Jesuits could reassemble the wreck. They couldn’t, but I discovered something I thought better: the religions of India.

Clearly, your book makes a strong case for women being admitted to the priesthood and for marriage to be permitted for the clergy. If you were the pope, beyond those two concerns, what major changes would you make?

What changes would I make—and in fact had Macrina make in the novel? As a boy I must have recited the Apostles’ Creed a thousand times. Many of you know it well. Here is the way I would say it today. “I believe in God the Father and Mother, creator of the universe. I believe in the ethical teachings of Jesus Christ, whose life was tragically cut short by corrupt men he outspokenly condemned. He was crucified like a criminal under Pontius Pilate, but his spirit did not die. Shortly after his death his closest friends saw him in spirit and took heart that he was, while in heaven, still with them; and they could not contain their joy; and out of that joy grew a young movement that would soon be labeled Christianity. I believe that the same divine spirit in Jesus is in all of us and that the Christian Church exists to help us grow into saints modeled after him. I believe that we are called to forgive and love each other and that we will be forgiven and loved in turn. I believe that life is everlasting and heaven is the ultimate destination for which all men and women were created. Amen.”

As pope, I would substitute this, or something like it, for the Nicene Creed. Missing would be the mythology that grew up like weeds around Jesus’ teachings. Gone would be Jesus’ physical resurrection from the dead and descent into hell, the virginity of Mary and her immaculate conception, Jesus’ Second Coming to bring the world to a close, and other pre-scientific beliefs that became dogmas but that we can now label superstition.

You say you attend an Episcopal church. In what ways does it differ from the Catholic Church?

As I say, they are cousins. Their liturgies are almost identical. Both are unfortunately waterlogged by the recitation of the Nicene Creed. But Episcopalians began ordaining women to the priesthood fifty years ago. A woman has even served as the primate, the head, of the Episcopal Church. An openly gay man has been ordained a bishop. Divorced men and women who have remarried outside the Church are not refused Communion. Women who have had an abortion can serve on the various church committees and even become deacons. In many Episcopal churches the priest asks all in attendance, whether baptized or not, to approach “Christ’s table” and receive communion. Sexual scandals arising from an enforced celibacy and all the damage done to children are rare—marriage is the norm. Anglican Catholics have moved on with the times. Roman Catholics have not. Or rather, the Vatican hasn’t. I say this because many Catholics think like Episcopalians. They are just not supposed to. Thus their spiritual lives are marred by what psychologists label cognitive dissonance. I’ve written this novel to help remove the dissonance.

All is not perfect, of course, in the Episcopal or any other Church. There is nothing in the doctrine to suggest that the God Episcopalians worship is the master architect of a trillion galaxies or that Jesus is a little less than the co-creator of this astonishingly big universe. In other words, present doctrine is not likely to attract well-educated, scientifically literate, relatively affluent parishioners. And that is too bad for everybody. The Church needs them if it is to grow, and they need the Church if they are to remain relatively sane in this maddening, soulless world.

Why put up with something so imperfect? Why go to church at all? Why wince your way through a creed you don’t believe in?

Sociologists have shown over and over that people who attend church on a regular basis are happier, healthier, and live longer. They even have better sex lives. You can see why at the “coffee hour” following Sunday church services. Lonely people, many of them widows, make friends. And the service itself—the music, the beflowered altar, the very shape of the building, and the priests and deacons that make it all run—is often quite impressive, even lovely. And, of course, the call to support the wretched of the earth and resist injustice brings out our better angels.

Like you, I parted ways with the Church many years ago. The adoration and worship aspects, all that bowing and kneeling before the altar, which took up 85 percent of the Mass, never made any sense to me, as it suggested a power-hungry anthropomorphic God – a Roman emperor or Egyptian king of sorts. Do you see that as a concern? If so, is there any hope for a change in the format of the Mass?

Yes, all this kneeling and bowing does feel awkward. And the liturgy is full of begging for God’s forgiveness for our sins, as if the more unworthy we make ourselves the more impressed God is. I would deemphasize sin in the liturgy. In my own way I do this by standing when many others kneel. But just as often kneeling and bowing are expressions of awestruck humility, or even wonder, which doesn’t strike me as improper at all. The greatest saints, the mystics, are often depicted in this posture. The attitude I cultivate in myself toward the Creator is gratitude. A prayer of thanksgiving for the great adventure of life on a physical planet, with all its joys and sorrows, its successes and failures, is the way I begin most of my days. I say it while sitting, not kneeling.

You deal with the afterlife in this book, at least to the extent of providing some clarification as to what purgatory and hell are all about, but we are still left with a very humdrum heaven, one that doesn’t attract most people. I’ve personally concluded that it is beyond human comprehension; however, such a conclusion doesn’t invite belief. Do you see a solution to this?

In her sermon on the afterlife, Macrina says, “For the newly dead, God’s Heaven is like the glare when our eyes aren’t ready. If we were lifted straight into Heaven the instant we died, we’d be uncomfortable. We’d feel out of place.”

In my previous novel, The Afterlife Therapist, I left my hero at the edge of a more evolved world that stretched beyond the astral plane into eternity: “Later, alone, seated on a terrace looking out over his luminous new world, with its strange horizons and landscapes—a beauty that almost frightened him, as if he were a person blind from birth suddenly gifted by some miracle with vision—Aiden wondered what lay ahead. His heart swelled as he anticipated what it might be. He imagined himself taking up a new post ‘in the infinite imagination of God’—those were his thoughts. He remembered a mantra Ravinder had taught him, ‘Arise, Master, and fill me wholly with thyself,’ and he seemed to tumble into the mouth of those words as he contemplated them. He became aware of a gradual loosening, a surrendering of his old personality, a sheering off of all that was old in him. He felt submerged in an immense Other that at the same time he felt one with. He felt known and loved by this Other, but the eye that looked into him and loved him was the same as his own eye. He remembered the phrase ‘from glory to glory.’ He was on his way. He felt that he had just awakened from a happy death.”

(I owe the language of this description, incidentally, to Meister Eckhart.) But that novel was set in the afterworld, while The Womanpriest is chained to more earthly concerns. Still, I might have worked in something like the above. Perhaps I should have.

And final thoughts?

My ultimate purpose in writing the novel was to reformulate Catholicism along the lines of the research you and I have devoted our lives to. As I wrote in my book The Afterlife Unveiled, “There are no rigid creeds or magical beliefs that souls have to accept. Whether you are a Baptist or a Catholic or a Mormon or a Hindu or a Buddhist or a Muslim or an Anglican is of no importance. Many of earth’s favorite religious dogmas are off the mark anyway, and the sooner they are recognized as such, the better. Experience in the Afterworld will generate, as a matter of course, a more enlightened set of beliefs that will better reflect better the way things really are than any of earth’s theologies.” I stand by those words. The new Catholicism that Macrina represents reflects these perspectives without identifying their origin.

Catholicism has given the world much that is great: its soaring Gothic cathedrals, its magnificent music from Palestrina to Duruflé, its millions of paintings that turn our attention heavenward, its contemporary orientation away from converting heathens to serving the poor, its increasingly ecumenical theology, and the throng of mystics it has nurtured in every age. Rather than turn my back on all this, I’ve chosen to embrace it and, in my own small way, attempt to reform it. Macrina’s history shows how this might happen. Once the Church opens the door to female ordination, this new Catholicism, marinated in teachings from the world of spirit, will quickly blossom. A real Macrina will someday ascend to the Seat of Peter. It might even happen before 2080, the date chosen for the novel.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next blog post; July 17

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

|

|