Do Spirits Influence Great Artists?

Posted on 23 October 2023, 9:51

“It is not every medium who is able to get into the headlines of the British press without being ridiculed, but this feat has been achieved by Herr Heinrich Nusslein,” psychical researcher Harry Price wrote in the November 1928 issue of Psychic Research, published by The American Society for Psychical Research. Price mentioned that more than 200 of Nusslein’s paintings were on view in London galleries at the time.

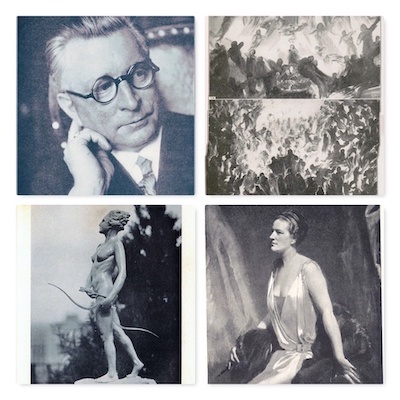

Price went on to explain that Nusslein (1879-1947, upper left photo), of Nuremberg, Germany, was advised by a business friend to develop the psychic powers he believed him to possess. Nusslein was described as “scornfully sceptical” but soon discovered he had a gift for automatic writing – mostly scraps of verse, odds and ends of forgotten knowledge, and, later, grandiose descriptions of his own psychic powers and productions. He then began producing some crude automatic drawings, the quality of which improved after some experimenting. This all took place during or around 1923, when Nusslein was in his mid-40s. Today, Nusslein is considered one of the most famous mediumistic or visionary artists. He claimed that deceased artists such as Albrecht Durer guided his hand, but many references stop short of saying that his visions were inspired by artists in the spirit world.

“In approximately two years, Nusslein, who had only one-ninth of normal vision, painted some two-thousand pictures,” Price further explained. “He always paints from imagination and memory, never from models, no matter what the subject. Except that ‘a spirit message’ on one occasion warned him to abstain from painting for six weeks, his powers are constant.” He added that Nusslein produces his pictures under varying degrees of consciousness and that many of them are painted from “visions” which appear to him and these were painted in complete darkness.

“The technique employed by Nusslein is very curious,” Price continued. “Some of the painting look as if his hands only had been used in producing them. The finger strokes are distinctly visible in many of his subjects and he has an almost uncanny gift for producing the impression of crowds of people or spirits, and processions with a very few strokes.” He completed a painting in anywhere from five minutes to forty minutes, his actions said to be “with lightning rapidity.” His ‘Lemure Scene from Faust’ (upper right, top) was completed in 18 minutes, while ‘Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony’ (upper right, bottom), required 23 minutes.

“Another method of obtaining a portrait is for [Nusslein] to get en rapport with a distant sitter,” Price wrote. “The resultant ‘psychic portrait’ (not necessarily a likeness) takes about three or four minutes. He can also ‘project himself’ into distant lands or epochs of the past and he then paints what he ‘sees’ there. In the same way, Nusslein is clairaudient and states that he ‘receives messages’ from historical characters of past ages. On one occasion he stated that he had received a message from ‘Peter Libidinsky,’ a magician at the Persian Court in the Middle Ages. The resultant painting, ‘The Magician,’ was a highly imaginative portrait.”

Spirit Sculptor’s Influence

It was also during the 1920s that Bessie Clarke Drouet, an American sculptor (1879 -1946, lower right photo) living in New York City began developing as an automatic writing medium while sitting with other mediums to observe various phenomena. In her 1932 book, Station Astral, Drouet tells of various influences on her work from the spirit world. At one sitting with direct-voice medium Maina Tafe, she asked her deceased father if anyone was helping her with her sculpture of Diana (lower left photo). Her father replied that many sculptors were there helping her, one of them being Bourdelle, a notable French sculptor, a contemporary of Rodin’s who finished many of his works after he died.

At a later sitting, a voice broke in, saying, “This is Ordway Partridge speaking. I heard you remark about the arm of Diana. I want you to know I helped you with it. I impressed you to walk over and change the position of it. Now I like it. I had been trying for a long time to find you in a receptive mood, so I could get a message through to you, and that day I did.” Partridge further commented that there were many sculptors in her studio, including Bourdelle, working with her.

At another sitting with Tafe, Drouet again asked if someone in the spirit world was helping her. “Peter Bruer, Peter Bruer, Peter Bruer, Berlin,” the response came, followed by a comment in the German language which nobody understood. The name was not recognized, but she was then told by another communicator, in English, that Bruer was a German sculptor who lived in Berlin and had died about three years earlier. At still a later sitting, Jean-Antoinie Houdon, a famous French neo-classical sculptor, communicated, stating that he and others were trying to assist her.

Seized with an Impulse to Paint

During January 1907, Dr. James Hyslop, the founder and director of the American Institute for Scientific Research, which was devoted to the study of abnormal psychology and psychical research, was consulted by Frederic L. Thompson, a New York City goldsmith. Thompson informed Hyslop, a former Columbia University professor of logic and ethics, that around the middle of 1905 he was “suddenly and inexplicably seized with an impulse to sketch and paint pictures.” Prior to that, he had no real interest or experience in art beyond the engraving required in his occupation. The impulses were accompanied by “hallucinations or visions” of trees and landscapes. He explained that he sometimes felt like a man named Robert Swain Gifford At times he would remark to his wife that “Gifford wants to sketch.”

Thompson had met Gifford some years earlier in the marshes of New Bedford, Massachusetts, as he was hunting and Gifford was sketching. Thompson recalled talking to Gifford for a few minutes on one occasion and just seeing him on a couple of other occasions. Also, he once called on Gifford to show him some jewelry, but that was the extent of their contact.

During the latter part of January, 1906, Thompson saw a notice of an exhibition of Gifford’s paintings at an art gallery and went to see them. While looking at one of the paintings on exhibition, Thompson heard a voice in his ear saying, “You see what I have done. Can you not take up and finish my work?” It was then that he learned that Gifford had died on January 15, 1905, some six months before he developed the interest in painting. “Whether genuine or not it had sufficient influence on the mind of Mr. Thompson to induce him to go on with his sketching and painting,” Hyslop said of the voice. “From this time on the impulse to paint was stronger, and between this date and the next year he produced a number of paintings of artistic merit sufficient to demand a fair price on their artistic qualities alone, his story being concealed from all but his wife.”

Hyslop arranged for Thompson to sit with three mediums, all resulting in evidence of influence from Gifford. “Superficially, at least, all the facts point to the spiritistic hypothesis, whatever perplexities exist in regard to the modus operandi of the agencies effecting the result,” Hyslop ended the report. (The Thompson-Gifford case was discussed in more detail in my blog of August 22, 2011.)

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next blog post: November 6

Read comments or post one of your own

|

Will Secular Students Eventually Turn to ‘Anxious Trembling’?

Posted on 09 October 2023, 7:55

When I see polls or surveys stating that more and more people in Generation Z are counted as secularists, atheists, humanists, or whatever label is applied to them, I react with ambivalence and mixed emotion. On the one hand, I see it as a positive sign that so many have recognized the apparent myths and distortions of various religious teachings, but, on the other hand, I fear that they have become nihilists, not understanding the difference between secular humanism and Cartesian mind-body dualism, the latter expanded to include the survival of consciousness at death.

To put it another way, in rejecting religion and its God, the secular humanist has seemingly assumed a concomitant relationship between God and an afterlife, and therefore has also repudiated the idea that consciousness survives death in a greater reality. The person has taken the common deductive approach of “no-god, no afterlife,” rather than an inductive one in which the evidence for consciousness continuing after death is overwhelming, thereby suggesting a Creator or Creative Force of some kind, even though it is probably beyond human comprehension. (Some of the best evidence is summarized in my book, No One Really Dies, even though it exceeds the boggle threshold of many skeptics.)

A recent release by the Secular Student Alliance introduces readers to 22 student activists scholarship recipients. Of the 22, at least 16 mention having been raised in a strict or devout religious environment, one in which the prejudices and bigotry they perceived conflicted with reason, compassion, and progressiveness. Fourteen of the 22 listed LGBTQ equality as a primary goal. One student states that her Catholic teachings “were weaponized to promote traditions of silence, shame, sexism, sexual abuse, and homophobia.” Another student was motivated by the need for “women’s reproductive justice,” A graduate student who received her bachelor’s degree in religious studies explained that “witnessing racism within her white Christian community during the Black Lives Matter protests further fueled her journey away from religion.” A number of them point to the need for science to prevail over religion.

Whatever motivates or inspires those 22 people or others in their generation, I have seen nothing to suggest that their secular humanism is not synonymous with nihilism. While there are some atheists who are not nihilists, the distinction is rarely recognized. An atheist rejects a higher power but not necessarily the idea that consciousness continues after death, while a nihilist rejects both and sees life as meaningless, beyond “having fun” and making it more comfortable and pleasurable for future generations. Such a worldview provides some meaning for young people who are not prepared to dig too deeply into the matter and ask, “to which generation full fruition?” or “to what end the progeny?”

Although seemingly having a purpose in life, one rooted in equality, the students do not see the bigger picture. For the most part, Carpe Diem (Seize the day!) is their philosophy and epicureanism their life style. At least that’s the way I see it from my distant porch (or perch).

Plodding, Pondering & Persisting

In his 2016 New York Times best seller, When Breath Becomes Air, Paul Kalanithi, a California neurosurgeon diagnosed with terminal lung cancer at age 36, addressed the “one day at a time” philosophy adopted by many nihilists by saying that such an approach didn’t help him. “What was I supposed to do with that day?” he asked, pointing out that time had become static for him as he approached the end. He considered more traveling, dining, and achieving a host of neglected ambitions, but he simply didn’t have the energy. “It is a tired hare who now races,” he explained. “And even if I had the energy, I prefer a more tortoise-like approach. I plod, I ponder. Some days, I simply persist.”

Kalanithi added that his medical training had been “relentlessly future-oriented” and all about delayed gratification, what one might be doing five years down the line. However, in his terminal condition, he wasn’t prepared to give much thought to what he would be doing beyond lunch.

In his 2010 book, The Undying Soul, Stephen J. Iacoboni, an oncologist who had witnessed thousands of deaths over some three decades of medical practice, stated that the real enemy facing terminal patients is not death, but the fear of death. He observed that many of his cancer patients had unrealistic expectations and didn’t want their hopes dashed. They pleaded for or demanded a cure. While trying not to extinguish what little hope there might have been, Iacoboni tried to be more honest with them than other doctors. Most of the terminal patients were, however, unable to accept the truth of their condition and lived their remaining days in a state of despair.

Iacoboni devotes separate chapters to different patients, using pseudonyms, and beginning with those who most feared death and died in anguish, before discussing several patients who quietly accepted their fate and departed with a puzzling serenity, seemingly even with eagerness and wonder.

Phillip, one of the patients in the first category, was 60 years old and had just retired from a career in computer technology when he was diagnosed with an aggressive case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. “Like me, Phillip had long before abandoned religious faith in favor of modern science,” Iacoboni writes. “Unlike faith, however, science provides no refuge when hope is gone.” As Phillip’s condition deteriorated and he marched toward the abyss in “utter isolation,” Iacoboni felt helpless, unable to offer him any comforting words. It was Phillip’s spiritually deprived death – so like many others he had attended – that prompted Iacoboni to search for answers outside of mainstream medicine. But he was so locked into the dogma of science that he didn’t know where to look. “It wasn’t so much the fact of their deaths that bothered me,” Iacoboni explains. “Rather it was the fact that they died without the comfort of finding peace within their hearts and souls before they passed on.”

Iacoboni observed that many people, so wrapped up in the “materialists’ narrow, spiritually crippling world view” had dismissed spiritual considerations in all the hustle and bustle of their everyday lives, then when facing imminent death, were desperate but didn’t know where to turn.

Tunnel Vision

As I further see it, tunnel vision has always been a characteristic of youth. Members of Generation Z are simply too young and inexperienced to fully grasp the worldview they’ve bought into. They are too focused on surviving in this world while being indoctrinated in hedonistic ways by the entertainment and advertising industries. They’re coached by professors not much older than they are and are further influenced by older professors stuck in the muck and mire of scientism. In embracing secular humanism, they celebrate a certain freedom from the moral fetters that were imposed upon them by their parents or religious communities. It’s not until a loved one is afflicted with a terminal condition or actually dies that so many permit death and all of its ramifications to rise to the threshold of consciousness.

As Michel de Montaigne, a 16th Century French statesman and philosopher wrote: “They come and they go and they trot and they dance, and never a word about death. All well and good. Yet when death does come – to them, their wives, their children, their friends – catching them unawares and unprepared, then what storms of passion overwhelm them, what cries, what fury, what despair.”

These secular humanists see science and religion as polarized positions, not realizing that some very renowned scientists have devoted countless years to studying psychical matters supporting survival under scientifically controlled conditions and independent of religion. The science may not be exact or pure, but it is as much science as we have with meteorology or with most of medicine. Professor Raynor Johnson, a British-Australian physicist, was one of them. “To sum it up,” he wrote in concluding one of his many books, The Imprisoned Splendor, “we have enough trustworthy evidence to anticipate our survival of the change called death.”

But the students will go to their computers and find a couple of primary encyclopedic reference that claims Johnson was clearly duped in all of his research, as were Sir Oliver Lodge, Sir William Barrett, Sir William Crookes, Dr. Richard Hodgson, Professor William James, Professor James Hyslop, and other esteemed scientists and scholars right up to the present day. They will dismiss the research and conclusions as bunk, not realizing and indifferent to the fact that many of these encyclopedic references are editorially biased in a materialistic and academic direction. Psychic phenomena are opposed to natural law and therefore none of them can be true is the position that some popular references offer gullible readers.

And so the secular humanist students continue with a nihilistic worldview, perhaps questioning it 50 years later after awakening to the twisting, distorting, misleading, incomplete, and uninformed explanations they have accepted over the years. The former students then rationalize that oblivion or total extinction of the personality will not bother them, as it will be just like sleep. They continue to repress the idea of death and extinction, all the while shaking in their boots when no one is looking.

As Professor William James, one of the pioneers of modern psychology, put it: “The luster of the present hour is always borrowed from the background of possibilities it goes with. Let our common experiences be enveloped in an eternal moral order; let our suffering have an immortal significance; let Heaven smile upon the earth, and deities pay their visits; let faith and hope be the atmosphere which man breathes in; and his days pass by with zest; they stir with prospects, they thrill with remoter values. Place around them on the contrary the curdling cold and gloom and absence of all permanent meaning which for pure naturalism and the popular-science evolutionism of our time are all that is visible ultimately, and the thrill stops short, or turns rather to an anxious trembling.”

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow books.

Next blog post; Oct. 23

Read comments or post one of your own

|