|

|

|

|

11-year-old medium shocks Unitarian minister

Posted on 28 May 2010, 14:14

As a very liberal Unitarian minister, Dr. Horace Westwood (pictured below) did not believe in any kind of afterlife. He was a humanist who believed that the objective of life was to make the world a better place for future generations. He did not stop to ask what future generations might strive for beyond comforts and pleasures once Utopia was attained. ‘The only immortality of which I was sure was the immortality of influence,’ he offered. ‘Beyond that, I had nothing to offer.’

Born in Yorkshire, England in 1884, Westwood emigrated to Canada in 1904, ministering in both the western and eastern parts of the country. As he explained in his 1949 book, There is a Psychic World, his philosophy relative to survival and the meaning of life began to slowly change in 1918 when he observed messages coming over a Ouija board at a friend’s house. Curious, he purchased a Ouija board and began experimenting in his own house with his wife and her cousin, who lived with them.

Their initial efforts were a failure. When Westwood’s four children and ‘Anna,’ the cousin’s 11-year-old daughter, asked what was going on, Westwood explained that it was kind of a toy. They asked to try it and he consented. Nothing happened with Westwood’s children, but when Anna tried it things did happen.

‘She had hardly touched it, when the indicator began to move with startling rapidity and with equally startling accuracy, spelling out words and sentences in complete and intelligent sequence,’ Westwood wrote. ‘But the subject matter of the sentence was extraordinary to say the least. Things were revealed which the child could not possibly have known. Circumstances and events were told concerning each adult that were not known to the other two. At times it was embarrassing, at least, to me.’

Westwood turned the board around and blindfolded Anna, but it made no difference. The indicator continued to deliver a wealth of information with swiftness and accuracy.

‘My immediate reaction was that the natural sensitivity of the child enabled her, by some process beyond my ken, to explore the subconscious levels of the minds of the adults and to bring forgotten and buried memories to light,’ Westwood explained.

The following day, Westwood made his own Ouija board with the letters in different places. He brought Anna to the board in his den while blindfolded and placed her hand on the tumbler over the board. ‘It was literally amazing,’ he recorded. ‘Her hand was not confused in the least. The tumbler found the letters with the same swiftness and accuracy as the day before. And to my great surprise the first message that came through was to the effect that I was a fool for my pains, the arrangements of the letters made not the slightest difference and that ‘they’ would prove that they were invisible entities seeking to communicate on the physical plane.’

Among the messages was one purporting to come from Fred, an old college friend who had died several years earlier. Still, Westwood refused to believe in spirits. ‘I positively refused to grant them any real existence,’ he continued, adding that he was certain it had to be some aspect of the subconscious mind that he did not understand.

Concerned about the effect of all this on Anna, Westwood discussed it with her, her mother, and his wife. As Anna seemed not to be affected in a negative way, he decided to continue with more experiments. Within a week, Anna developed the power of automatic writing. ‘It made no difference whether we blindfolded her or not, she wrote with the same perfect ease and accuracy. Her pencil never faltered and never was there the slightest hesitation in recording answers to questions that were asked.’

One message came from a child whose parents Westwood knew. For privacy concerns, he referred to her under the pseudonym ‘Charlotte Summers.’ She had been in the adjoining ward of the hospital Dr Westwood was in for surgery during 1913. She ‘passed over,’ at the age of six, before he left the hospital.

Charlotte began by giving her name and their mutual hospital experiences, as well as the circumstances of her death. ‘As the message continued, she revealed an intimate knowledge of her parents’ family life both during her earthly sojourn and since,’ Westwood documented. ‘She then made clear the purpose of her communication.’ She wanted Westwood to contact her mother, who had ceased to grieve, and let her know that she was still alive. ‘Give her to understand that I’m always near and that I am so happy over baby brother.’ Charlotte communicated in Anna’s hand.

Westwood was reluctant to contact the Summers and tell them of the communication, especially since he was still not sure that it was not all some kind of trick of the subconscious combined with mental telepathy. However, he proceeded to call them and received the reaction he had feared. Mr. Summers was shocked that Westwood would believe in such ‘nonsense’ and wanted nothing to do with it. However, about a month later, Mr Summers, apparently at the urging of Mrs. Summers, called Westwood and requested that Anna be brought to their home.

‘In response to the many questions asked through Anna of the alleged Charlotte [by the Summers], the replies indicated a wealth of detailed information entirely beyond any possible knowledge [Anna] might have possessed,’ Westwood wrote. ‘The parents were convinced that the communication were evidential and that through Anna they had come into touch with the daughter who had ‘passed over’ some five years before.’

Not long after the automatic writing began, Anna wrote messages from two apparently different sources. One signed her name ‘Ruth’ and the other ‘Ralph.’ They claimed to have been stenographers in Washington, D.C. in the employment of the U.S. Government and said they died together about two years earlier while in their late twenties. They provided some data about their life, but Westwood, still resisting the survival hypothesis, made no attempt to follow up and verify the information. ‘I was not interested in communing with the departed, and the problem of proving or disproving survival was not in my mind,’ Westwood explained as he wrote the book some three decades later.

While messages had come from other ‘entities’ earlier, they now came only from Ruth and Ralph. Anna suddenly became an expert typist while receiving messages from Ruth and Ralph. ‘Anna had never played with a typewriter,’ Westwood wrote. ‘But under control and blindfolded, she would operate the machine with perfect ease as though she possessed experienced hands. Yet, without control and without the blindfold, she had to pick out the letters, painfully, one by one.’

Westwood would place typed questions in the typewriter, blindfold Anna, who had no prior knowledge of the questions, and then receive swift replies from Ruth and Ralph. He even spoke with Anna about other matters as her fingers typed replies.

At one sitting, Ralph suggested a game. He instructed Westwood to take a ‘rook’ from his chess set and place a ping-pong ball on it, then to use his long briar tobacco pipe as a golf club and to hit the ball toward a certain object without knocking down the rook. ‘It was a task requiring the greatest delicacy in coordination and skill,’ Westwood related, mentioning that his four children and Anna all gave it a try. ‘Not once did any of us succeed. Usually, we knocked down the rook with ball. When we succeeded in hitting the ball without knocking down the rook, it went wild and we missed our object.’

Ralph then communicated that Westwood should blindfold Anna and place her in position. ‘Through Anna, Ralph assumed a stance, then swinging the pipe as a club, he struck,’ Westwood continued the story. ‘He did not miss, the rook did not fall, and the ball flew with precise aim and hit the object. We set ourselves up as targets around the room, and one by one, he caused the ball to hit us all.’ Anna remained blindfolded through it all.

Westwood then challenged Ralph to a game of chess. Westwood had previously taught Anna the game, although her skills were elementary. Nevertheless, as a precaution he again blindfolded her. ‘It was an extraordinary sight to watch her fingers move the pieces on the board,’ Westwood wrote. ‘But it was more marvelous still to realize that a genuine game was in process.’ Later, after Ralph had departed, Westwood tried to get Anna to play the game, but she could not see the pieces and therefore was unable to play.

There were times when Ruth and Ralph were absent. Westwood asked them what they were doing when they were not communicating with him. They informed him that they had duties and tasks, primarily that of welcoming to their side those who had just passed over. Ruth and Ralph explained that their time at the Westwood home was their recreation period. They further explained that their job of greeting new souls was very stressful, especially since many of them failed to realize that they were ‘dead.’ Some of those who had passed over from the battlefield continued to want to fight. It was as if they were men struggling in a nightmare.

Westwood pointed out that Anna never went into a trance. ‘Never, for one moment, was there even the suggestion of a lapse of consciousness,’ he explained. ‘While the alleged controls never ‘broke through’ or manifested in my absence, or without my expressed wish, when they did come through, Anna was always master of the situation. In almost every experiment, for example, she would at times throw off the control in order to make some personal comment or observation, thus showing that her own mind was watchful and fully alert.’

One evening, Westwood asked Ruth if she would play on the piano through Anna, who had taken a few lessons but was by no means an accomplished pianist. Ruth informed him that she was not musical, but that the following evening she would bring a friend named Kate, so gifted. The following evening, Westwood blindfolded Anna and sat her at the piano. ‘As long as I shall live, I shall never forget that night,’ Westwood reported. ‘She began with a slow melody, the like of which I had never heard before, for it was solemn in its majesty and almost unearthly in its beauty. As I watched the child play, the bodily action and the finger technique were entirely different from Anna’s own.’

Later, the alleged Kate (through Anna) took pencil and paper and began to write rapidly. She told Westwood that the scale structure on her side was different and thus it was difficult to express herself as she would have liked to. ‘Yet the whole performance was on an elevated plane, indicating a mental range and musical understanding far beyond the child’s normal power,’ Westwood wrote.

At another sitting, during which a number of family friends gathered, Ruth took charge and asked each person to write a question on a piece of paper, leave it unsigned, then fold the paper and put it into a container. Westwood then shook the container and gave it to Anna, who took out the pieces of paper one by one. In each case, Ruth identified the writer and answered the questions. In two or three cases, the answer was ‘I don’t know.’ One of the guests asked what the price of a certain stock would be on the stock exchange the following day. ‘Have you been imbibing too freely from the contents of your well-stocked cellar?’ Ruth responded to that question. This was during prohibition and the response was very embarrassing to the guest. Westwood pointed out that Anna, herself, could not possibly have known of the guest’s ‘well-stocked cellar.’

Still, Westwood remained a ‘doubting Thomas,’ not wanting to believe in the spirit hypothesis and thinking that Anna’s subconscious was somehow producing the phenomena. One night, Ruth and Ralph left and a nameless spirit who would only designate himself as ‘X’ began communicating. ‘I realized that we were in the presence of a decidedly superior intelligence, as far above Ruth or Ralph in intellectual grasp as a Ph.D. would be above a college freshman,’ Westwood documented. ‘X’ began discussing philosophical matters, some of which were beyond Westwood’s grasp. ‘The general point of view was that the underlying, in fact the all-permeating reality was consciousness, and that the universe by and large was designed for ‘being’ and ‘beings’ in an infinite series of gradations,’ Westwood further reported, admitting that his intelligence was no match for ‘X’.

Westwood then proposed an experiment. He would blindfold Anna and he would then walk backward into another room, the library. With his back to the bookcase, he would select a book at random. Without looking at the book, he would open it and place it on a buffet in the dining room with the open pages down. He would then return to Anna and ask ‘X’ to indicate the number of the right-hand page at which the book was opened and write the first 10-12 words. ‘X’ agreed to the experiment, which was carried out as Westwood requested, several other adults in attendance.

‘I do not hesitate in making the confession that I walked to the buffet with some trepidation,’ Westwood continued. ‘I did not believe that what I had proposed was within the realm of possibility. However, when I reached the buffet and compared the script (from ‘X’ through Anna), they corresponded. The script gave the correct number of the page. However, as to the writing, there was one slight variation. Instead of the words from the top of the page, they were the opening words of the first paragraph. Also, there was one slight discrepancy, the first word ‘Remember’ was spelled ‘Rember.’ Otherwise, the text was perfect.’

On Christmas Day, 1918, a young girl named Virginia, the niece of a member of Westwood’s congregation was killed in a tobogganing accident. Two days later, Ruth communicated that Virginia was there and she would allow her to communicate through Anna, even though Virginia was still dazed.

‘The first symptom was that of bewilderment bordering on fear,’ Westwood wrote. ‘In fact, the first words that came through were, ‘Where am I? I want my mother.’ This was repeated several times as she (Virginia through Anna) gazed around the room.’ Westwood told her that there was no need to be afraid, that she was in the study of the church. Virginia then settled down and asked how her mother and baby brother were. Westwood noted that neither he nor Anna knew that she had a baby brother. He asked other questions of Virginia and later confirmed the responses as fact with Virginia’s aunt.

While Westwood claimed to have no interest in survival, he wrote that he was forced to believe in it after his experiences with Anna, who lost her powers after about three years, upon the departure of Ruth and Ralph.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

Earthly mistakes fester in the afterlife

Posted on 14 May 2010, 15:38

Indications are that we take our mistakes and unfinished business with us when we die and that they can continue to fester with us in the spirit world. Consider the sitting that Dr Minor Savage (below) had with Leonora Piper, the famous Boston medium. Savage was told that his son, who had died at age 31 three years earlier, was present. “Papa, I want you go at once to my room,” Savage recalled his son communicating with a great deal of earnestness. “Look in my drawer and you will find a lot of loose papers. Among them are some which I would like you to take and destroy at once.”

The son had lived with a personal friend in Boston and his personal effects remained there. Savage went to his son’s room and searched the drawer, gathering up all the loose papers. “There were things there which he had jotted down and trusted to the privacy of his drawer which he would not have made public for the world,” Savage ended the story, commenting that he would not violate his son’s privacy by disclosing the contents of the papers.

As further reported by Savage and also recorded in the records of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR), the Rev. W. H. Savage, Minot’s brother, and a friend of Harvard Professor William James, the man who discovered Mrs. Piper, sat with Piper on Dec. 28, 1888. Phinuit told him that somebody named Robert West was there and wanted to send a message to Minot. The message was in the form of an apology for something West had written about Minot “in advance.” W. H. Savage did not understand the message but passed it on to Minot, who understood it and explained that West was editor of a publication called The Advance and had criticized his work in an editorial. During the sitting, W. H. Savage asked for a description of West. An accurate description was given along with the information that West had died of hemorrhage of the kidneys, a fact unknown to Savage but later verified.

In a sitting by W. H. Savage two weeks later, West again communicated, stating that his body was buried at Alton, Illinois. He gave the wording on his tombstone, “Fervent in spirit, serving the Lord.” Savage was unaware of either of these facts, but later confirmed them as true.

“Now the striking thing about this lies in the fact that my brother was not thinking of this matter and cared nothing about it,” Minot Savage ended the story, feeling that this ruled out mental telepathy on the part of the medium. “There was no reason for the [apology] unless it be found in simply human feeling on his [West’s] part that he had discovered that he had been guilty of an injustice, and wished, as far as possible, to make reparation, and this for peace of his own mind.”

A Mother’s Grief

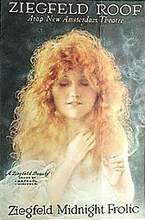

There have been many messages from the spirit world suggesting that the grief of loved ones left behind weighs heavily on the departed soul. Such was the message communicated by Olive Thomas (below), a popular Hollywood actress of the silent-screen era, who died of a medication overdose during September 1920.

Communicating with J. Gay Stevens, a New York journalist and a member of the ASPR, through medium Chester Michael Grady, Thomas informed Stevens that she needed to get word to her mother that her death was accidental, not a “scandalous suicide” as had been reported by the press. She explained that when she couldn’t sleep she reached for a bottle of sleeping pills but took the wrong bottle, one very similar in appearance. It contained bichloride of mercury, which killed her.

When Stevens contacted Thomas’ mother, the mother wanted nothing to do with him, assuming that, as a journalist, he was just trying to add to the scandal. But Thomas pleaded for Stevens to make further efforts to convince her mother. Over a period of a dozen sittings, Thomas provided Stevens with personal information that had not been public knowledge, hoping that her mother would realize that she was in fact communicating. But the mother still resisted, concluding that as a journalist Stevens had special ways of gathering information. Moreover, her pastor told her that it must be the work of Satan.

Thomas insisted, however, that Stevens keep trying. She then provided some very evidential information that she felt certain would convince her mother that she was alive in the spirit world and communicating. She said that all of her jewelry had been returned to her mother after her death, except one item – her favorite brooch. She told Stevens that the brooch got caught up in the lining of a pocket in the steamer trunk now in her mother’s attic. She also told Stevens one of the pearls, the third from the top on the right, had come out of its setting and was loose in the tissue paper surrounding the brooch.

When Stevens brought this information to Thomas’ mother, the mother reluctantly agreed to go to the attic and search the steamer trunk. Finding the brooch with the loose pearl was enough to convince her that her daughter, not Satan, was actually communicating. She accepted the explanation that her daughter did not commit suicide and this apparently relieved much of her grief and also gave Olive a certain peace of mind.

Change in Will

One of the victims of the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania by a German U-boat was Sir Hugh Lane, an art connoisseur and director of the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin. He was transporting lead containers with paintings of Monet, Rembrandt, Rubens, and Titian, which were insured for $4 million and were to be displayed at the National Gallery. It was reported by survivors that Lane was seen on deck looking out to Ireland before going down to the dining saloon just before the torpedoes struck.

On the very night of the disaster, Hester Travers Smith (above) and Lennox Robinson were sitting at a Ouija board in Dublin, Ireland. As was their usual practice, Travers Smith, the oldest daughter of Professor Edward Dowden, a Shakespearian scholar, and Robinson, a world-renowned Irish playwright, sat blindfolded at the board, their fingers lightly touching the board’s “traveler,” a triangular piece of wood which flies from letter to letter under the direction of a spirit control.

They had experienced several controls over their years of operating the ouija board, but on this particular night the control was a spirit known to them as Peter Rooney. Rooney would be in touch with others on his side and deliver their messages for them if they lacked the experience to communicate on their own. Reverend Savell Hicks sat at the table between Travers Smith and Robinson, copying the letters indicated by the traveler.

“I am Hugh Lane, all is dark,” was spelled out by the traveler, although Travers Smith and Robinson were blindfolded and had no clue as to the message. In fact, they were conversing on other matters as their hands moved rapidly. After several minutes, Hicks told Travers Smith and Robinson that it was Sir Hugh Lane coming through and that he told them he was aboard the Lusitania and had drowned.

While they had heard of the disaster, none of the three was aware that Lane was a passenger on the ship. They continued receiving messages from Lane, who told them that there was panic, the life boats were lowered, and the women went first. He went on to say that he was the last to get in an overcrowded life boat, fell over, and lost all memory until he “saw a light” at their sitting. To establish his identity, Lane gave Travers Smith an evidential message about the last time they had met and talked.

“I did not suffer. I was drowned and felt nothing,” Lane further communicated through Peter Rooney that night. He also gave intimate messages for friends of his in Dublin.

Lane continued to communicate at subsequent sittings. As plans were underway to erect a memorial gallery to him, he begged that Travers Smith let those behind the movement know that he did not want such a memorial. However, he was more concerned that a codicil to his will would be honored. He had left his private collection of art to the National Gallery in London, but the codicil stated that they should go to the National Gallery in Dublin. Because he had not signed the codicil, the London gallery was reluctant to give them up. “Those pictures must be secured for Dublin,” Lane communicated on January 22, 1918, going on to say that he could not rest until they were.

At a sitting that September, Sir William Barrett, the distinguished British physicist and psychical researcher, was present. Prior to the sitting, Travers Smith and Barrett discussed how evidential the messages from Lane were to them, although they could understand why the public doubted. After the sitting started, a man who said he had died in Sheffield communicated first. Then, Travers Smith recalled, Robinson’s arm was seized and driven about so forcibly that the traveler fell off the table more than once. It was Lane, who was upset because of the doubts expressed relative to his communication.

More regrets over a will

On November 10, 1928, Mollie Ross sat with Geraldine Cummins (below), the renowned Irish automatic writing medium, in London. “Mo..Mo…Molly. I am here. I see you,” Molly’s deceased sister, Alice, communicated through Cummins’ hand. “It’s all true. I am alive. The pain went at once. I felt suffocating. Then, just after I got that awful chocking, I felt things were breaking up all about me. I heard crackling like fire and then dimness. I saw you bending down with such a white face and you were looking at me, and I wasn’t there.”

Alice said that she regretted not having treated her second son, who was living in East Africa, as an equal to Ronald. (Molly confirmed that Ronald was her sister’s favorite and that Ronald was favored in Alice’s will.)

Another deceased sister, Margaret, took control of the pencil and said that Alice was having a hard time “managing the words.” Margaret then communicated that Alice also regretted treating her husband badly. Molly noted that this was also very evidential as Alice “bullied her husband dreadfully.”

Margaret then mentioned that Alice still resented the fact that Margaret cut her out of her will and left her share to Charles, their brother, who had no need of the money. This was another very evidential fact to Molly, as it was clearly unknown to the medium. “She hasn’t forgotten yet the way I left my money,” Margaret wrote. “She feels it would have made a difference in her last days.”

Molly told Margaret that Alice’s family was managing financially. “Good,” Margaret replied. “I will tell her that, then she won’t bother about things. The fact of the matter is, she came out of the world with a dark cloud of years of troubled thought about money. It all accumulated and clung about her. But I think now it will be slowly dissipated…All that worrying before her death left her in a very scattered state of mind.”

Borrowed item not returned

Sometime around 1890, Henry Ward Beecher (below) told his friend, Dr. Isaac K. Funk, about a valuable coin, called “The Widow’s Mite,” owned by another friend, Professor Charles West, of Brooklyn, NY. During 1894, Funk, a partner in the American company, Funk & Wagnalls, borrowed the coin from West so that it could be illustrated in The Standard Dictionary, which the company published.

As Funk was to later recall, he gave the coin to his brother, Benjamin, the company’s business manager, and asked him to return it to Professor West after the photographic plate was made. Benjamin then gave the coin, along with another coin, both in a sealed envelope to H. L. Raymond, head cashier of the company. Raymond placed the envelope in the drawer of a large combination safe, where it would remain forgotten for some nine years.

It was in February of 1903 that Funk, also a member of the ASPR, was told about an apparently gifted medium in Brooklyn. On his third visit to this medium, the medium’s spirit control said that Beecher, who was unable to communicate directly, was concerned because of an ancient coin. “This coin is out of its place and should be returned,” the message came through. “It has long been away, and Mr. Beecher wishes it returned, and he looks to you, doctor, to return it.”

Funk pressed for more information and was told that it was in a large iron safe in a drawer under a lot of papers. At his office the next day, Funk had the bookkeeper check the company safe. There, they found the coin in a little drawer in the safe under a lot of papers. Since Professor West had also died, the coin was then returned to his son.

Although Beecher was not responsible for holding on to the coin, he apparently felt some responsibility for it or it may have been that West was unable to communicate and asked Beecher to remind Funk that it has not been returned.

The biggest regret

There are many other stories suggesting that we take our concerns, anxieties, mistakes, and regrets with us to the afterlife, but there have also been a number of communications saying that the biggest regret is not having found out more about the spirit world when alive.

Communicating with Allan Kardec, the distinguished French researcher of yesteryear, a spirit identified as Van Durst, who had been employed by the government before dying at age 88 in 1863, told Kardec that he very much regretted not paying any attention to spirit matters before his death. “If, before quitting the earth, I had known what you know, how much more easy and agreeable would have been my initiation into this other life,” Van Durst said. “I should have known, before dying, what I had to learn afterwards, at the moment of separation; and my soul would have accomplished its disengagement much more easily.”

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

|

|