Caught in the Middle: Renaissance Man Charles Richet

Posted on 23 December 2019, 9:37

There were three schools of thought relative to mediumship and other psychic phenomena during the early years of psychical research. The predominant school, that of scientific fundamentalism, held that it was all fraudulent – just so much trickery or tomfoolery. Most belonging to this school did little or no research, choosing to form their opinions on the non-scientific nature of the various phenomena and the belief that it represented a return to the pre-Darwinian religious humbug.

A second school, one including many esteemed scientists and scholars who thoroughly studied the phenomena, held that genuine phenomena existed and that it strongly suggested a world of spirits and the survival of consciousness at death. This school recognized that there were many charlatans and even some genuine mediums who didn’t want to disappoint observers and occasionally cheated, consciously or unconsciously, when their powers failed them. Many in this school had hundreds of observations on which to base their conclusions.

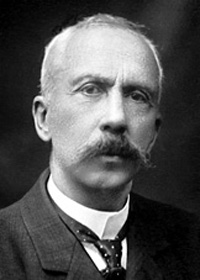

The third school agreed with the second school as to the reality of psychic phenomena but did not see it as suggesting spirits or survival. Rather, they opined that it was all a product of the mind not yet understood by science. One of the leaders of this school was Dr. Charles Richet, winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize in Medicine. A Frenchman, Richet (below) was a physician, physiologist, chemist, bacteriologist, pathologist, psychologist, inventor, philosopher, explorer, aviator, poet, novelist, playwright, editor, author, and psychical researcher. After practicing medicine for about 10 years, he served as professor of physiology at the medical school of the University of Paris for 38 years. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for his research on anaphylaxis, the sensitivity of the body to alien protein substance. He also contributed much to research on the nervous system, anesthesia, serum therapy, and neuro-muscular stimuli. He served as editor of the Revue Scientifique for 24 years and contributed to many other scientific publications. He was referred to by writers of his time as an ideal European, a visionary, and a Renaissance man.

Richet’s interest in psychical research began around 1872 when, as a medical student, he observed phenomena later classified as extra-sensory perception (ESP). His real research in the field seems to have begun in 1892 when he observed the mediumship of Eusapia Palladino, an illiterate Italian woman. He would go on to study a number of other famous mediums, including Marthe Béraud of France, Leonora Piper of the United States, and Franek Kluski and Stefan Ossowiecki, both of Poland.

Many of Richet’s studies were under strictly controlled conditions, including the medium being strip-searched in a laboratory and behind locked doors, there being no possibility of confederates or hidden material smuggled into the room. “When I think of the precautions that we have taken, twenty times, a hundred times, a thousand times, it is unacceptable that we were all twenty times, a hundred times, a thousand times, misled,” Richet wrote of his research in psychical matters, further stating that all possible psychological explanations had to be exhausted before considering the idea of discarnate, or spirit, activity.

An excellent introduction to Richet’s research and views was just recently released by White Crow Books. Titled Charles Richet: A Nobel Prize Winning Scientist’s Exploration of Psychic Phenomena, the book is authored by Dr. Carlos S. Alvarado, probably the most knowledgeable person in the world in the fields of psychical research and parapsychology. In this 218-page book, Alvarado focuses on Richet’s psychical research and his views, describing his book as “a reference work presenting many summaries of studies, bibliographical sources, and evidential claims about psychic phenomena for the pre-1922 period.” (Further discussion here is not necessarily from Alvarado’s book, as I draw from my own study of Richet.)

Metapsychics, as Richet referred to the study of psychical matters, was something to be approached in a purely scientific manner. “We must remain on the earth, take all theory soberly, and only consider humbly whether the phenomenon studied is true, without seeking to deduce the mysteries of past or future existences,” Richet wrote in his 1923 book, Thirty Years of Psychical Research. At the same time, Richet admitted that the “discarnate agency” explanation – one holding that there are intelligent beings intervening in our lives while exercising some action over matter – was the simplest explanation for some cases.

Many researchers of the day were convinced that Palladino was a charlatan, at best a mixed medium, sometimes producing genuine phenomena and other times cheating. However, Richet, who had more than 200 sittings with her, defended her. “Even if there were no other medium than Eusapia in the world, her manifestations would suffice to establish scientifically the reality of telekinesis and ectoplasmic forms,” he wrote, going on to explain that in her trance condition “the ectoplasmic arms and hands that emerge from the body of Eusapia do only what they wish, and though Eusapia knows what they do, they are not directed by Eusapia’s will; or rather there is for the moment no Eusapia.”

One of most interesting and intriguing stories about Palladino, involving Richet, was reported by Dr. Cesare Lombroso, a renowned Italian neuropathologist. As set forth in his 1909 book, After Death-What? Lombroso wrote: “On the evening of the 28th of September (1892), while her hands were being held by MM. Richet and Lombroso (referring to himself), she complained of hands which were grasping her under the arms; then, while in trance, with the changed voice characteristic of this state, she said, ‘Now I lift my medium up on the table.’ After two or three seconds the chair with Eusapia in it was not violently dashed, but lifted without hitting anything, on to the top of the table, and M. Richet and I are sure that we did not even assist the levitation by our own force. After some talk in the trance state the medium announced her descent, and (M. Finzi having been substituted for me) was deposited on the floor with the same security and precision, while MM. Richet and Finzi followed the movements of her hands and body without at all assisting them. … Moreover, during the descent both gentlemen repeatedly felt a hand touch them on the head.”

The voice and invisible hands referenced by Lombroso were supposedly those of John King, Palladino’s spirit control. However, since recognizing the presence of spirits was not “scientific,” John King was to them only some kind of secondary personality emerging from Palladino’s subconscious. Moreover, while those accepting the spirit hypothesis saw much of the so-called cheating as movements by John King controlling Palladino’s body, those not accepting the reality of spirits could only conclude that Palladino was pulling off some sleight-of-hand, whether called conscious or unconscious fraud.

Marthe Béraud (given the pseudonym “Eva C”) also impressed Richet. With her, Richet witnessed many strange materializations, some of them appearing like cardboard cutouts. While many laughed at the photos of these materializations, wondering how any scientist could take them seriously, Richet responded: “The fact of the appearance of flat images rather than of forms in relief is no evidence of trickery. It is imagined, quite mistakenly, that a materialization must be analogous to a human body and must be three dimensional. This is not so. There is nothing to prove that the process of materialization is other than a development of a completed form after a first stage of coarse and rudimentary lineaments formed from the cloudy substance.” This cloudy substance was otherwise referred to as ectoplasm by Richet.

Richet pointed out that there are stages in the materialization process: “[First,] a whitish steam, perhaps luminous, taking the shape of gauze or muslin, in which there develops a hand or an arm that gradually gains consistency. This ectoplasm makes personal movements. It creeps, rises from the ground, and puts forth tentacles like an amoeba. It is not always connected with the body of the medium but usually emanates from her, and is connected with her.” The flat materializations, he explained, came in the rudimentary phase, a sort of rough draft in the phase of building up. Often the materializations stalled in the rudimentary stage, apparently due to lack of power by the medium or by the spirits (assuming spirits), thereby resulting in bizarre manifestations that only invited more scoffs from the fundamentalists of science.

That ectoplasm is a scientific fact, Richet had no doubt, though he called it “absurd.” “Spiritualists have blamed me for using this word ‘absurd’ and have not been able to understand that to admit the reality of these phenomena was to me an actual pain,” he explained his position. “But to ask a physiologist, a physicist, or a chemist to admit that a form that has a circulation of blood, warmth, and muscles, that exhales carbonic acid, has weight, speaks, and thinks, can issue from a human body is to ask of him an intellectual effort that is really painful. Yes, it is absurd, but no matter – it is true.”

While clearly accepting the reality of mediumship and other psychic phenomena, Richet remained skeptical as to whether the evidence suggested spirits and survival. He said he would not allow himself to be blinded by rationalism and that he opposed the spiritist hypothesis only “half-heartedly” because he was unable to bring forward any wholly satisfactory counter-theory. “In very many cases the spiritist hypothesis is obviously absurd – absurd because it is superfluous – and again absurd because it assumes that human beings of very moderate intelligence survive the destruction of the brain,” he stated his position. “All the same, in certain cases – rare indeed, but whose significance I do not disguise – there are, apparently at least, intelligent and reasoned intentions, forces, and wills in the phenomena produced; and the power has all the character of extraneous energy.”

Is mortality vs. immortality really a superfluous matter? One can only wonder how such a brilliant man could have come to such a conclusion. Certainly, there is a paradox involved there. Also, Richet’s comment about humans of a very modest intelligence surviving death suggests that he was influenced by the religious belief that all spirits are omniscient or at least of a very high order, giving no heed to revelation of the time indicating that we transition with the same consciousness we had in the material life.

Sadly, the same “intellectual” mindset continues today. It is the “scientific” approach.

Then again, if, as Victor Hugo was supposedly told by a spirit, “doubt is the instrument which forges the human spirit” (see blog of 11-11-19), we should be thankful for Richet’s wisdom. Truth is so abstract, so paradoxical.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Next blog post: January 7

Read comments or post one of your own

|

What Do We Remember After Death?

Posted on 09 December 2019, 9:47

When my wife said not long ago that I should try to communicate with her after I die, I pondered on what I might be able to do or say that would be evidential to her. I told her that I am not sure how much I’ll remember or how much of that I would be able to get through a medium or otherwise. Based on psychical research, it’s usually a matter of the communication being by ideas and symbols and then converted into language by a medium. The ideas and symbols are often misinterpreted.

A few days after my wife made the request, I was attempting to clear much of the clutter in a closet, some of it old photos and papers inherited from my parents after their transitions. I came upon a letter I wrote to them in 1958 from Quantico, Virginia. I told them of attending a football game with two friends and then finding my car would not start after the game, requiring a new coil to be installed by a mechanic dispatched by Triple A. However, I have absolutely no recollection of the game, the friends, or the car problem. I attempted to dig into my subconscious for some recollection of them, but I was unsuccessful. There were many other things in that and other letters my parents had saved that I could not recall. However, I do have flashing memories of little incidents here and there, many of them seemingly as insignificant as that football game and car problem. Why remember some and not others? I searched for an emotional aspect in those I could remember and found little or none in most of what I do remember.

During my youth, I attended dozens of baseball games, from New York to San Francisco. Yet, there are only two memories in my brain from all those games – two very vivid mental pictures. One is getting the great Jackie Robinson’s autograph as he approached the clubhouse from the parking lot. As Robinson was a boyhood idol, I can understand recalling that one. However, the other memory has long mystified me and suggests some kind of precognition. It involved another player from the Brooklyn Dodgers, Don Newcombe.

It was a hot July day in 1949 at the old Polo Grounds in New York with the Dodgers playing the New York Giants. I was 12 at the time and was seated in deep centerfield with my seven-year-old brother. Newcombe had just been called up from the minor leagues by the Dodgers a week or two earlier and I had never heard of him until that game, which, I believe, was only his second game in the majors. When he left the game about the seventh inning, he departed through the centerfield exit to the clubhouse, right below me. I remember reacting with a thought, “Wow! What a big guy he is.” For some mystifying reason, I took a mental snapshot of him, one that I can still picture very clearly and sharply, more than 70 years later.

I was up close to many other standout ballplayers during my youth, filling an autograph book with 50 or more names, some now legendary. But I have retained no such mental snapshot of any of them, only Newcombe, who, unlike Robinson, was not one of my favorites. That snapshot of Newcombe resurfaced in my consciousness every now and then over the next 45 or so years, and then around 1994, a friend called me at work. Knowing that I was an old Dodgers fan, he said he was accompanying Don Newcombe to a talk he was giving to a local Alcoholics Anonymous group and wanted to bring him by my office the next day. Newcombe and I had a long talk about the old Dodgers and I told him about remembering that 1949 game, which he did not seem to have a particular recollection of. We met again on another occasion to continue our discussion.

I remain mystified as to why the mental snapshot of Newcombe (below with me) on the field is the only one from so many games of baseball that I held on to. If it had not resurfaced in my consciousness over those 45 years before meeting him, I might understand it, but it was a recurring picture over those 45 years, a dozen or more times, and precognition is the only thing I can come up with.

Just a few days before writing this, a friend invited me to a pre-Christmas luncheon and his email invitation to me and several others asked that we come prepared to relate a memorable Christmas story. While I’m reasonably certain I enjoyed every Christmas of my youth, I could recall no particular moment and had no particular mental snapshots of anything worth relating.

All that makes me wonder how effective I would be if, after death, I try to communicate something evidential through a medium. What might I remember that would be very evidential to my wife? If I do remember it, will the idea be properly interpreted and symbolized by the medium? Will I remember our unusual bank account password? If I do remember it, will I be able to somehow get it through to the medium? There is no symbol for the password.

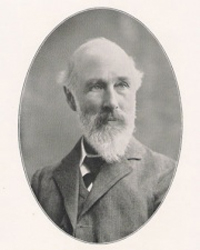

After his death in 1925, Sir William Barrett, (below) a distinguished British physicist and a co-founder of the Society for Psychical Research, began communicating with his wife, Florence Barrett, a physician and dean of the women’s college of medicine in London, through several mediums, including trance medium Gladys Osborne Leonard. He told her that he had to learn how to slow down his vibration in order to communicate with her. “Sometimes I lose my memory of things from coming here,” he continued. “I know in my own state but not here. In dreams you do not know everything, you only get parts in a dream. A sitting is similar; when I go back to the spirit world after a sitting like this I know I have not got everything through that I wanted to say. That is due to my mind separating again.”

Sir William went on to explain that in the earth body we have the separation of subconscious and conscious and that when we pass over they join and make a complete mind that knows and remembers everything. However, when he brings himself back into the physical sphere, the conscious and the subconscious again separate and he forgets much. “I cannot come with my whole self, I cannot.”

When Lady Barrett asked him to elaborate, Sir William pointed out that he has a fourth dimensional self which cannot make its fourth dimension exactly the same as the third. “It’s like measuring a third dimension by its square feet instead of by its cubic feet,” he continued, “and there is no doubt about it I have left something of myself outside which rejoins me directly I put myself into the condition in which I readjust myself.”

At a later sitting, Sir William explained that when he was in his own sphere he would remember a name, but when he came into the conditions of a sitting he could not always remember it. “The easiest things to lay hold of are what we may call ideas,” he communicated. “A detached word, a proper name, has no link with a train of thought except in a detached sense; that is far more difficult than any other feat of memory or association of ideas. If you go to a medium that is new to us, I can make myself known by giving you through that medium an impression of my character and personality, my work on earth, and so forth. Those can all be suggested by thought impressions, ideas; but if I want to say ‘I am Will,’ I find that is much more difficult than giving you a long, comprehensive study of my personality. ‘I am Will’ sounds so simple, but you understand that in this case the word ‘Will’ becomes a detached word.”

Lady Barrett had wondered why he had identified himself as “William,” when she knew him as “Will,” and why he had called her “Florrie,” when he knew her as “Flo.” He explained that it was a matter of being able to get certain names through a medium easier than other names. Much depended on the medium.

Sir William added that if he wanted to express an idea of his scientific interests he could do it in twenty different ways. He could begin by showing books, then giving impressions of the nature of the book and so on until he had built up a character impression of himself, but to simply say “I am Will” was a real struggle for him.

Initially, Lady Barrett was skeptical and asked for proof that the communicator was her late husband. Sir William responded by mentioning a tear in the wall paper in the corner of his room and a broken door knob, both of which they had discussed a month or so before his death, and the fact that they had now been repaired. This was especially evidential to Lady Barrett.

For further verification, Lady Barrett asked Sir William to tell her the circumstances of his death. He accurately responded that he had died in the armchair in the drawing room as Lady Barrett accompanied a visitor to the front door downstairs. She discovered his lifeless body upon her return. Lady Barrett was certain that Mrs. Leonard could not have known such detail. Sir William added that when he passed over he had no pain at all and that he was at once met by his mother and father and others.

Not being able to think of anything that a medium might be able to properly interpret or symbolize, I told my wife that I might be at too high a vibration to effectively communicate with those at the earth vibration…or I could be at such a low vibration that I might not even realize I am dead, in which case I probably won’t be able to communicate at all. If, however, I am at the right vibration and am able to remember the password and get it through, the skeptic will conclude that the medium successfully fished for it or even telepathically picked it up from wife’s brain. So best not to even try.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Next blog post: Dec. 23

Read comments or post one of your own

|