|

|

|

|

What does being “Happy” in the New Year mean?

Posted on 29 December 2018, 13:23

Like many other people, I have been wishing numerous friends and acquaintances a “Happy New Year!” as we approach 2019. But how many of us really stop to think what we are wishing for the person? What does it mean to be “happy”? Is the kind of happiness we are wishing for someone the same as that Thomas Jefferson and other authors of the Declaration of Independence had in mind when they wrote that among our inherent and inalienable rights are “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

According to James R. Rogers, a professor of political science at Texas A & M University, the “happiness” that Jefferson and the others had in mind does not refer to a subjective emotional state. “It meant prosperity or, perhaps better, well-being in the broader sense,” Rogers states. “It included the right to meet physical needs, but it also included a significant moral and religious dimension.” Rogers cites a 1786 letter between James Madison and James Monroe, the fourth and fifth presidents of the United States, in which Madison comments that “nothing can be more false” than to assume that happiness refers to the immediate augmentation of property and wealth. Rogers further notes that the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 affirms that “the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government essentially depend upon piety, religion and morality…”

Rogers goes on to say “that the upshot of those references and many others from that era suggest that happiness should be understood as a sort of “virtuous felicity,” although refined by Christian sensibilities. He observes that modern liberalism conflicts with the pursuit of happiness in that it seems to assume an objective moral order from which a person may not alienate himself. If I am reading Rogers correctly, he is saying that the element of “liberty” is paramount for the secular progressives, the result being limited moral constraints.

No doubt our more “progressive” leaders, as well as our academic philosophers thoroughly indoctrinated in materialism, would resist all that, while leaning toward a much more Epicurean view of it, perhaps substituting the word “fun” for happiness and understanding it as “eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die.” The humanists among the progressives would be quick to say that morality is important, then making a failed attempt to argue that the masses can achieve high moral standards without religion’s idea of a “larger life” following the earthly life.

As I see it, the root cause of all the chaos in the world today is that people have been brainwashed by the entertainment and advertising industries to believe that life is all about “having fun.” Carpe Diem! Seize the day! Live in the moment! It is the philosophy of the secularists and others who reject the idea that consciousness survives death.

In his book The Immortalist, humanist philosopher Alan Harrington showed himself to be a rare exception to the usual closed-minded, humanist mindset, writing, “An unfortunate awareness has overtaken our species. Masses of men and women everywhere no longer believe that they have even the slightest chance of living beyond the grave. The unbeliever pronounces a death sentence on himself. For millions this can be not merely disconcerting but a disastrous perception.” As Harrington viewed it, when people are deprived of rebirth vision, they “suffer recurring spells of detachment, with either violence or apathy to follow.” Harrington saw mass-atheism as responsible for most, if not all, of society’s ills, including misplaced sexual energy. “Orgies, husband and wife swaps, and the like, more popular than ever among groups of quite ordinary people, represent a mass assault on the mortal barrier.”

Erich Fromm, another realistic humanist philosopher, agreed with Harrington. “The state of anxiety, the feeling of powerlessness and insignificance, and especially the doubt concerning one’s future after death,” Fromm wrote, “represent a state of mind which is practically unbearable for anybody.”

Philosopher and pioneering psychiatrist William James rejected the nihilistic or humanistic approach to life. “I can, of course, put myself into the sectarian scientist’s attitude, and imagine vividly that the world of sensations and scientific laws and objects may be all,” he offered. “But whenever I do this, I hear that inward monitor which W. K. Clifford once wrote, whispering the word ‘bosh!’ Humbug is humbug, even though it bear the scientific name, and the total expression of human experience, as I view it objectively, invincibly urges me beyond the narrow ‘scientific’ bounds.”

While recognizing that their philosophy dooms them to eternal nothingness, the humanists, atheists, nihilists, skeptics, rationalists, secularists, materialists, reductionists, whatever handle they proudly hang on themselves, rationalize that their “truth” combined with on-going science gives meaning to life. That is, life is all about providing a better world for future generations. However, in all their altruism, they stop short of explaining to what end the progeny or to which generation full fruition.

If a future generation experiences a world of peace with unsurpassed comforts and conveniences, what will then give meaning to their lives? In effect, life remains short-term and meaningless for all generations under the non-believer’s repressed awareness. Our founding fathers apparently realized this in stating that the pursuit of happiness is an inalienable right, not happiness itself. That is, if a future generation were to achieve pure, unconditional, unbounded happiness, one in which there is no adversity and all comforts are fulfilled, that generation would have no incentive to pursue anything and may very well find itself where Nero was when Rome burned. It is the pursuit that gives life purpose.

And with that, I wish all the readers of this blog a Happy New Year!

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Next blog post: January 14

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

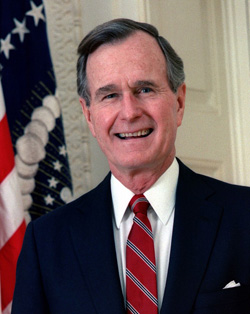

Finishing like Bush 41

Posted on 10 December 2018, 10:04

When former President George W. Bush (Bush 43) ended the eulogy for his father, former President George H. W. Bush (Bush 41 below), last week by saying something to the effect that his father was looking forward to a reunion with his beloved wife, Barbara, and their daughter, Robin, I could envision thousands of nihilists sitting in front of their television sets and reacting to the comment with a self-righteous snort, snarl, or sneer. I could hear their words, such as “How absolutely ridiculous!” and “How unscientific for men of that stature to believe in such religious superstition!” I wondered how a nihilist would end the eulogy. Perhaps, “And now that my father is totally extinct, his personality completely obliterated, we need to forget him and get on with life, no matter that our lives are totally meaningless.” Rather than being a “send-off,” as one newspaper headlined the Bush ceremonies, such a memorial service would be a dreary and depressing reminder that life is simply a march into an abyss of nothingness.

So many of the nihilists I encounter in person or on the Internet seem to be young people brainwashed by academia. Death is too many years down the road for them to have any anxieties about their extinction. I admit that when I interviewed Horatio Fitch (below) in 1984, I hadn’t given much thought to dying. I was 47 at the time and still had both feet fully planted in the material world, working two jobs – my day job in insurance claims management and my weekend job as a freelance reporter for the morning daily and a columnist for a national magazine. In between and around those jobs there were family responsibilities and training up to 100 miles a week in failed efforts to outrun Father Time. Life was all about living and there was little time to think about dying and death. It was too far in the future, but Horatio’s situation got me to thinking about it.

Horatio was 83 at the time, living alone in a desolate cabin in the mountains of northwest Colorado, his wife having died a few years earlier. He was snowbound at the time of my telephone interview and his nearest neighbor some distance away. While his phone worked, he had little or no television reception and his eyes were so bad that he was unable to read. He said he spent most of his time listening to classical music. As I talked with him, I pictured a man dying alone in the middle of nowhere.

Two years earlier, the movie Chariots of Fire had won the Academy Award as the best picture of 1981. The movie was about two British runners, both sprinters, who were hoping to win a gold medal in the 100-meter dash at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris. But one of them, Eric Liddell, a divinity student from Scotland, refused to participate in the 100 because the race was on a Sunday, a day that was sacred to him. Instead, he entered the 400-meter run.

Representing the United States, Horatio, an engineering student at the University of Illinois, had broken the world record in his 400-meter heat earlier that day and shaped up as the favorite. However, Liddell gloriously won the race with Horatio taking the silver medal. But then, even more than now, a silver medal didn’t count for much. Between 1924 and 1982, Horatio was asked to speak about his Olympic experience on only two occasions, once in 1928 and again sometime in the mid-30s. While he secretly cherished his silver medal and had fond memories of his Olympic participation, he got on with life and seldom mentioned what he had done that July afternoon in Paris. “It wasn’t that big of a thing until after the movie,” he told me with a hearty laugh.

The actor playing Horatio Fitch in the movie had a very small part – a few seconds on the ship to Paris and then a few seconds in the race itself – but it was enough for people to start contacting him for talks at various community and church functions. And there were interviews, like mine, preceding the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, 60 years after Horatio’s Olympic effort. “I enjoy talking about it,” he said. “Heck, I don’t have that much else to do these days.” He also found some humor in the ironical, even paradoxical, aspect of the situation – losing the race had brought him a little fame, even if 60 years later. Moreover, if he had won the race, he would have robbed the future screenwriters of a story and the movie would not have been made.

When I heard that Horatio died the following year, I wondered if he died alone in his mountain cabin. I tried to put myself in the same situation and felt certain that I would really struggle with such solitude, especially if not able to read. Now that I am nearly as old as Horatio was when I interviewed him, I again wonder what it would be like to live alone and die alone in such a desolate place, no human being within shouting distance. Fortunately, Bush 41 was at the other extreme in this respect, having all of his large family around him when his spirit body left the physical body. Bush 41 appears to have had the ideal departure.

I interviewed Horatio for the sports page and so I didn’t ask him about his beliefs, but I can’t imagine being 83 years old, living alone in the wilderness, unable to read, and with nothing to do but listen to records without a belief that consciousness survives death. I know some people say that such finality doesn’t bother them, but I always suspect that it is nothing more than bravado to cover up for their inability to grasp things that don’t easily fit nicely into their “intellectual” paradigm. To quote William James: “The moralist must hold his breath and keep his muscles tense; and so long as this athletic attitude is possible all goes well – morality suffices. But the athletic attitude tends ever to break down and it inevitably does break down even in the most stalwart when the organism begins to decay, or when morbid fears invade the mind.”

Carl Gustav Jung, one of the founders of modern psychiatry, said that the majority of his patients were those who had lost their faith. “They seek position, marriage, reputation, outward success or money, and remain unhappy and neurotic even when they have attained what they were seeking,” he explained. “Such people are usually confined within too narrow a spiritual horizon. Their life has not sufficient content, sufficient meaning.” He referred to the reality of most people as “a submission to the vow to believe only in what is probable, average, commonplace, barren of meaning, to renounce everything strange and significant, and reduce anything extraordinary to the banal.”

Jung recalled that while in medical school he was fascinated when he read about psychic phenomena as observed by such noted scientists as William Crookes and Johann Zöellner, but when he spoke of them to his friends and classmates, they reacted with derision and disbelief, or with anxious defensiveness. “I wondered at the sureness with which they could assert that things like ghosts and table-turning were impossible and therefore fraudulent, and on the other hand at the evidently anxious nature of their defensiveness.”

Concerning the whole idea of an afterlife, Jung stated he was convinced that it is “hygienic” to discover in death a goal toward which one can strive and not to do so robs the second half of life of its purpose. “I therefore consider the religious teaching of a life hereafter consonant with the standpoint of psychic hygiene,” he wrote, adding that it is desirable to think of death as only a transition – one part of a life process that is beyond our knowledge and comprehension. Apparently, Bush 41 had that mindset and hopefully Horatio did, too. It’s unfortunate that the nihilists don’t get it.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

|

|