|

|

|

|

Is Einstein Still Laughing? The Strange Case of Rudi Schneider

Posted on 26 April 2021, 9:07

“I could find no evidence of fraud or trickery, and, while retaining an alert and critical attitude of mind throughout, I had a strong feeling of some mysterious power working from within the cabinet, a power for which I could imagine no mechanical or pneumatic contrivance as a cause – at least such as would be possible under the conditions of the séance.”

So wrote Dr. William Brown, F.R.C.P., Wilde Reader in Mental Philosophy at Oxford University and founder of the Institute of Experimental Psychology, in a letter to The Times of London of May 7, 1932 in reference to the mediumship of a 23-year-old Austrian, Rudi Schneider, (below) who was known primarily for producing physical phenomena, including materialized hands, occasionally a full materialization, levitations of the medium, floating tables, and other telekinetic movements. Brown was part of a group studying Schneider in England. The group included astronomer Christopher Clive (better known as C. C. L.) Gregory, founder of the University of London observatory, and later, the husband of Anita Gregory, the author of The Strange Case of Rudi Schneider.

According to Anita Gregory, a British psychologist, Professor Brown was subjected to a good deal of ridicule at Oxford, notably by Professors Albert Einstein and Frederick Lindemann, both world-renowned physicists. They are said to have laughed at the phenomena reported by Brown and a number of other reputable scientists. “No way!” they must have scoffed.

Anita Gregory first heard about Schneider while attending a lecture given by Brown toward the end of the 1940s. When Brown told of witnessing objects flying about the room and a hand materializing out of nothing while Schneider was in a trance state, she could not accept that a man of Brown’s standing in the academic world and in psychology would believe such things. “I recall vividly how I reacted to Dr. Brown’s lecture: by impatient contempt, a little tinged with pity,” she wrote in the Introduction of her book. “How could a learned man believe such nonsense? And how could he bring himself to admit such absurd notions in public? Why didn’t someone stop him from making such a fool of himself? I never entertained even for a moment the possibility that there could have been some real experience underlying his assertions.”

Gregory did not believe Brown was insane or the victim of some magician; she simply considered it so absurd that she gave it no further consideration until after her marriage in 1954 to C. C. L. Gregory, when she found out that he was also present in many of the experiments with Schneider and fully supported Brown’s version. In fact, C. C. L. sat next to Schneider and controlled his arms and legs during a number of the experiments. Along with another scientist, he developed an infrared apparatus used in registering infrared “occultations” during the experiments. Her husband’s testimony prompted Anita Gregory to begin a detailed search into all records of the experiments carried out with Schneider.

Although Gregory’s study of the research records takes 425 pages to explain, it is not Schneider’s mediumship that makes the book especially interesting and intriguing; it is the hubris involved among the many scientists who studied him. Harry Price, an engineer who established the National Laboratory of Psychical Research in London, is quoted by Gregory from a 1929 article: “I wonder how many of my readers are aware of the number of squabbles, petty jealousies and open feuds that are taking place among those investigating psychic phenomena. In nearly every country where two or more societies or investigators are working there exists a state of affairs which is little less than a scandal. Quarrels, backbiting, lawsuits, sharp prejudice, scandal-mongering, the gratification of personal spite, these things are rampant to the detriment of the science of psychical research and a paralyzing drag on the wheel of progress. It would be bad enough if the psychic brawlers confined their activities to their own frontiers, but they do not – the internecine warfare is international…”

One might assume from that statement that Price was the victim of his peers in psychical research, but he emerges from Gregory’s research as the real “monger.” “When he wished for widespread popular support he would court spiritualist opinion, conceding that belief in survival was accepted among the majority of those who occupied themselves with such matters, and hinting that he himself shared this belief; when, on the other hand, he wished to present himself as the champion of a new scientific discipline he would belabor spiritualism as a more of benighted superstition from which he personally had rescued the subject,” Gregory surmised. “This dual attitude, which is by no means confined to Price, must also be taken into consideration when assessing anyone’s claims in the field.”

Perhaps the two most dedicated researchers studying Schneider were Dr. Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, a German physician who had 88 sittings with Schneider, and Dr. Eugene Osty, a French physician who carried out 77 experiments with him. Both men were convinced that he was the real deal. “We are sure, absolutely sure, of the reality of the phenomena,” Osty reported, “but we cannot say the same for our interpretation.” The issue there was whether “Olga,” the entity who took control of Schneider’s body when he became entranced, was the spirit of a deceased human, as she claimed to be, or a “secondary personality” surfacing from Schneider’s subconscious mind. It was much more “scientific” to assume the latter and thereby dismiss any suggestion of spirits of the dead, something written off by the fundamentalists of science as pure superstition.

“The phenomena were personal in the sense that there was every appearance of someone, an invisible or barely invisible ‘person’ acting upon the everyday world, moving objects, knotting handkerchiefs, patting sitters on the head or boxing their ears, as the case might be,” Anita Gregory explained, describing Olga as a “phantom person” who at times was “capable of producing tangible effects on the physical world, and of somehow or another partially clothing herself in visible and tangible substance.”

Dr. Alois Gatterer, a Jesuit priest and professor of physics at Innsbruck University, reported observing a full phantom on April 12, 1926, which he described as “light, misty, and indistinct and which seemed to increase and decrease in size and luminosity.” He also observed materialized hands at two different sittings with Schneider and was absolutely certain they were not Schneider’s hands. “I do not hesitate to express my personal conviction on the subject of paraphysical phenomena…,” he wrote.

Many other scientists and intelligent people observed Schneider under strictly controlled conditions and attested to the genuineness of the phenomena, but some, no doubt concerned with the criticism of men like Einstein and Lindemann, hesitated in their reports, theorizing that one of the scientists in attendance “could have been” an accomplice. Dr. Karl Foltz theorized that the phenomena “could be” explained on the supposition that Schneider made use of the mechanical vibrations of the different objects in the room and that the floor “must have been” shaky. Some, like Dr. Eric Dingwall of the Society for Psychical Research, flip-flopped, first vouching for the authenticity of the phenomena but then retreating and saying there “could have been” an accomplice. “The pressure on the scientist to recant is unrelenting, and if the errant researcher succumbs and returns to the straight and narrow path of denial, the scientific community breathes a sigh of relief, and allows him or her to forget the lapse and the reasons for that lapse with the blandest discretion,” Anita Gregory opined.

After studying him in Austria on a number of occasions, Price arranged to have Schneider brought to London for 27 séances between February 9 to May 3, 1932. Although eight of those 27 sittings were totally negative, and it had become clear earlier that his mediumship was in decline, enough phenomena were produced to convince Price, Brown, C. C. L. Gregory, Lord Charles Hope, Professor D. F. Fraser-Harris, an eminent biologist, Professor A. F. C. Pollard, an authority on engineering, and others that paranormal phenomena were being produced and that trickery was not a factor. “If Rudi were ‘exposed’ a hundred times in the future, it would not invalidate or affect to the slightest degree our considered judgment that the boy has produced genuine abnormal phenomena while he has been at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research,” Price reported. “We have no fault to find with Rudi; he has cheerfully consented to our holding any test or any séance with any sitter or controller. He is the most tractable medium who has ever come under my notice.”

Although Anita Gregory never met Rudi Schneider and looked upon him as some kind of huckster when Dr. Brown told of him in a lecture, she did a complete about-face after her detailed study of the research records. “If one insists upon regarding the phenomena as fraudulent, then one is forced to attribute the majority of instances as being due to an accomplice, an outsider, who was somehow or another smuggled into the séance room,” she concludes, wondering how Rudi, who spoke no English and had no money of his own, could have arranged for an accomplice in London and how that accomplice could have gone undetected. She adds that all who knew Rudi considered him an exemplary person.

But the story doesn’t end there. Almost a year after Rudi left London, and after other researchers had added to earlier research in further validating him, Price claimed that a double-exposure photograph from the 1932 series that he had previously overlooked revealed that Rudi’s arm was free of control at the same time the displacement of a handkerchief was taking place. Price, himself, was holding Rudi’s hand at the time, but he claimed that because of a toothache he was not attentive to the matter and did not realize Rudi had freed his arm. The double exposure is very fuzzy and inconclusive, and it was argued by others that even if he had momentarily freed his arm, possibly a shock reaction to the photographic flash, he was too far distant from the phenomenon to have affected it. But Price’s denouncement provided the sensationalism that the press and the skeptics desired, and Schneider was labeled a cheat by many. “Indeed, [Price’s] motives were only too obvious to all those involved: to discredit his ‘enemies,’ that is those researchers who had ‘taken Rudi away from him’ and who had declined to accept him as the ultimate and final authority on the phenomena of Rudi Schneider,” Anita Gregory concludes. In effect, if I am interpreting all this correctly, Price didn’t intend to totally discredit Schneider. He just wanted to “muddy the waters” and create the need for additional testing in his laboratory.

Is it any wonder that psychical research gave way during the 1930s to parapsychology, in which spirits of the dead and the subject of life after death were ignored as the focus turned to extra-sensory perception (ESP) and psychokinesis (PK)? The famous “Margery” case of the 1920s, in which Dr. Dingwall also seems to have flip-flopped from acceptance to doubt, and that of medium George Valiantine, during the late 1920s and early ‘30s, involved so much conflict and friction among researchers that it became clear that there would never be a meeting of the minds when it came to physical phenomena or any phenomena in which “spirits” were supposedly involved. The Rudi Schneider case seems to have put the final nail in the coffin of survival research.

Nevertheless, the cumulative evidence seems to have been overwhelming and one can only wonder if Professor Einstein is still laughing.

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow Books.

Next blog post: May 10

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

Examining the Fear Factor on the “Titanic”

Posted on 12 April 2021, 20:40

It is difficult to measure the fear factor on the Titanic during the first two hours following its collision with an iceberg, because the preponderance of testimony suggests that very few of the passengers really believed that the “unsinkable” ship would sink. “One of the most remarkable features of this horrible affair is the length of time that elapsed after the collision before the seriousness of the situation dawned on the passengers,” Robert W. Daniel, a 27-year-old first-class passenger from Philadelphia, testified. “The officers assured everybody that there was no danger, and we all had such confidence in the Titanic that it didn’t occur to anybody that she might sink.”

Daniel jumped into the ocean before the ship went down and was picked up by one of the lifeboats. He said that “men fought and bit and struck one another like madmen,” referring to those in the water attempting to save themselves. He was reportedly picked up naked with wounds about his face, and then nearly died from the exposure to the cold before he was rescued.

Since April 14-15 marks the 109th anniversary of the tragic sinking of the great ship, I thought it a good time to revisit the story, as told in more detail in my 2012 book, Transcending the Titanic, specifically to look at the fear factor. As discussed in the book, once it was realized that the ship was going down, four different approaches to one’s fate can be recognized: 1. Dignified Expectation; 2) Stoic Resignation; 3) Controlled Trembling; 4) Panic.

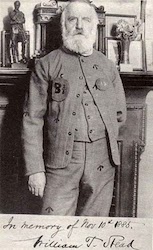

Four survivors reported seeing William Thomas Stead (below) at various places in the 2 hours and 40 minutes that elapsed between the time the floating palace hit an iceberg and the time it made its plunge to the bottom of the North Atlantic. All of them told of a very composed and calm man, one prepared to meet his death with “dignified expectation.”

Stead, a popular British journalist on his way to New York to give a talk on world peace at Carnegie Hall, is remembered by many for his books and articles intended to demonstrate the reality of survival after death as well as to assist in a spiritual revival. In 1909, three years before his death, he published Letters from Julia, a series of messages purportedly coming to him by means of automatic writing, from Julia T. Ames, an American newspaperwoman, who had died some months earlier.

Juanita Parrish Shelley, a 25-year-old second-class passenger from Montana who was traveling with her mother, saw Stead assisting women and children into the lifeboats. “Your beloved Chief,” Shelley later wrote to Edith Harper, Stead’s loyal secretary and biographer, “together with Mr. and Mrs. (Isidor) Strauss, attracted attention even in that awful hour, on account of their superhuman composure and divine work. When we, the last lifeboat, left, and they could do no more, he stood alone, at the edge of the deck, near the stern, in silence and what seemed to me a prayerful attitude, or one of profound meditation. You ask if he wore a life-belt. Alas! No, they were too scarce. My last glimpse of the Titanic showed him standing in the same attitude and place.”

Frederick Seward, a 34-year-old New York lawyer, said that Stead was one of the few on deck when the iceberg was impacted. “I saw him soon after and [I] was thoroughly scared, but he preserved the most beautiful composure,” Seward, who boarded lifeboat 7, recalled.

Certainly, Stead (below) was not the only victim of the Titanic to face death with relative composure and calmness, although in many cases it may not have been easy to distinguish between Stead’s “dignified expectation” and the “stoic resignation” of those of little faith or with a nihilistic view. One likely would have to search the eyes for hope or despair in order to discern the difference. In either case, the person might be described as brave, courageous, or, if aiding others to his own detriment, as heroic. Indeed, the stoic might be considered more brave or more courageous, though more pathetic, since he did not have the support of hope and expectation, as Stead apparently had.

Major Archie Butt, (below) a 46-year-old aide to President William Howard Taft, was praised by several surviving passengers. “I questioned those of the survivors who were in a condition to talk, and from them I learned that Butt, when the Titanic struck, took his position with the officers and from the moment the order to man the lifeboats was given until the last one was dropped from the sea, he aided in the maintenance of discipline and the placing of the women and children in the boats,” wrote Captain Charles Crain, a passenger on the Carpathia, which picked up survivors. “Butt, I was told, was as cool as the iceberg that had doomed the ship, and not once did he lose control of himself. In the presence of death he was the same gallant, courteous officer that the American people had learned to know so well as a result of his constant attendance upon President Taft.”

Benjamin Guggenheim, the millionaire smelter magnate, asked John Johnson, his room steward, to give Mrs. Guggenheim a message if he (Johnson) survived, which he did. “Tell her that I played the game straight and that no woman was left on board this ship because Benjamin Guggenheim was a coward. Tell her that my last thoughts were of her and the girls.” Multi-millionaire John Jacob Astor, 47, is said to have initially ridiculed the idea of leaving the ship in lifeboats, saying that the solid decks of the Titanic were safer than a small lifeboat. However, by 1:45 a.m. he had changed his mind and helped his 18-year-old wife, Madeleine, board the last lifeboat. He asked Second Officer Charles Lightoller if he could also board and was told that no men were allowed. Astor then stood back and reportedly stood alone as others tried to free the remaining collapsible boat.

Lawrence Beesley, a 34-year-old teacher and second-class passenger who later wrote a book about his experience and observations, described an initial calmness or lack of panic. “The fact is that the sense of fear came to the passengers very slowly – a result of the absence of any signs of danger and the peaceful night – and as it became evident gradually that there was serious damage to the ship, the fear that came with the knowledge was largely destroyed as it came. There was no sudden overwhelming sense of danger that passed through thought so quickly that it was difficult to catch up and grapple with it – no need for the warning to ‘be not afraid of sudden fear,’ such as might have been present had we collided head-on with a crash and a shock that flung everyone out of his bunk to the floor.”

The ship’s band, or orchestra, was praised by all surviving passengers. Beesley recalled that they began playing around 12:40 a.m., an hour after the collision, and continued until after 2 a.m. “Many brave things were done that night, but none more brave than by those few men playing minute after minute as the ship settled quietly lower and lower in the sea and the sea rose higher and higher to where they stood; the music they played serving alike as their own immortal requiem and their right to be recorded on the rolls of undying fame.”

Although the captain had given the order “women and children only” many men, including Beesley were able to board the lifeboats. Beesley explained that lifeboat 13 was only about half full when he heard the cry, “Any more ladies?” The call was repeated twice with no response before one of the crew looked at him and told him to jump in. After he was in the boat, three more ladies and one man showed up and boarded. “We rowed away from her in the quietness of the night, hoping and praying with all our hearts that she would sink no more and the day would find her still in the same position as she was then,” Beesley continued, stressing that the belief remained strong that the Titanic could not sink and it was only a matter of time before another ship showed up and took everyone aboard. “Husbands expected to follow their wives and join them either in New York or by transfer in mid-ocean from steamer to steamer … It is not any wonder, then, that many elected to remain, deliberately choosing the deck of the Titanic to a place in the lifeboat. And yet the boats had to go down, and so at first they were half full; this is the real explanation of why they were not as fully loaded as the later ones.”

Some women apparently remained on the ship because the risk of boarding a lifeboat seemed greater than that of staying on the ship. “Many believed it was safer to stay on board the big liner even wounded as she was, than to trust themselves to the boats,” Albert Smith, a ship’s steward, was quoted. The lifeboats hung 70-75 feet above the ocean as crew members struggled to lower them in jolts and jerks. “Our lifeboat, with thirty-six in it, began lowering to the sea,” Elizabeth Shutes, a 40-year-old first-class passenger and governess to passenger Margaret Graham, recounted. “This was done amid the greatest confusion. Rough seamen all giving different orders. No officer aboard. As only one side of the ropes worked, the lifeboat at one time was in such a position that it seemed we must capsize in mid-air. At last the ropes worked together, and we drew nearer and nearer the black, oily water.” Shutes added that there was some reluctance to row away from the ship, as it felt much safer being near it, so certain they were that it would not sink.

As the situation became more dire, there were reports of men rushing the life boats, jumping in them as they were being lowered, and even stowing away in them under cover. “Some men came and tried to rush the boat,” crew member Joseph Scarrot, in charge of lifeboat 14, testified. “They were foreigners and could not understand the orders I gave them, but I managed to keep them away. I had to use some persuasion with a boat tiller. One man jumped in twice and I had to throw him out the third time.”

Fifth Officer H. G. Lowe reported that one passenger boarded one of the boats dressed like a woman, with a shawl over his head. As the boat was being lowered he noted a lot of passengers along the rails “glaring more of less like wild beasts, ready to spring.” He said he fired three warning shots and did not hit anybody.

Annie May Stengel, a 43-year-old first-class passenger whose husband, Charles, escaped the ship in a later lifeboat, reported that four men jumped into her lifeboat as it was being lowered, one of them Dr. Henry Frauenthal, a New York City physician, who landed on her and knocked her unconscious.

But the stories of bravery or simple resignation in the face of fear far outnumber those of cowardice. One of the most celebrated cases of bravery reported by the press immediately following the tragedy was that of Rosalie Straus, the 63-year-old wife of New York department store magnate Isidor Straus, mentioned above. She was observed about to enter a lifeboat when she reversed directions and was overhead to say to her husband, “We have lived together for many years, where you go, I go.” Witnesses then saw the two settle in deck chairs. An April 17 article in the San Francisco Chronicle, quoted Mrs. Samuel Bessinger, a relative, as saying that Mrs. Straus may not have realized the gravity of the situation, but even if she had, she doubted that she would have left her husband, so devoted she was.

Next blog post: April 26

Michael Tymn is the author of The Afterlife Revealed: What Happens After We Die, Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife, and Dead Men Talking: Afterlife Communication from World War I.

His latest book, No One Really Dies: 25 Reasons to Believe in an Afterlife is published by White Crow Books.

Read comments or post one of your own

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mackenzie King, London Mediums, Richard Wagner, and Adolf Hitler by Anton Wagner, PhD. – Besides Etta Wriedt in Detroit and Helen Lambert, Eileen Garrett and the Carringtons in New York, London was the major nucleus for King’s “psychic friends.” In his letter to Lambert describing his 1936 European tour, he informed her that “When in London, I met many friends of yours: Miss Lind af Hageby, [the author and psychic researcher] Stanley De Brath, and many others. Read here |

|